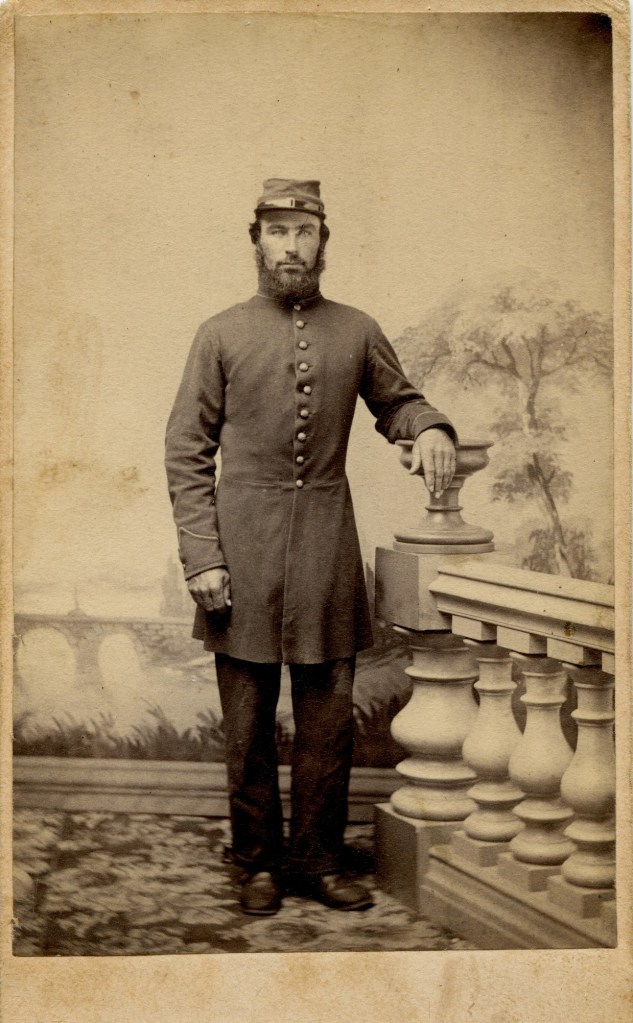

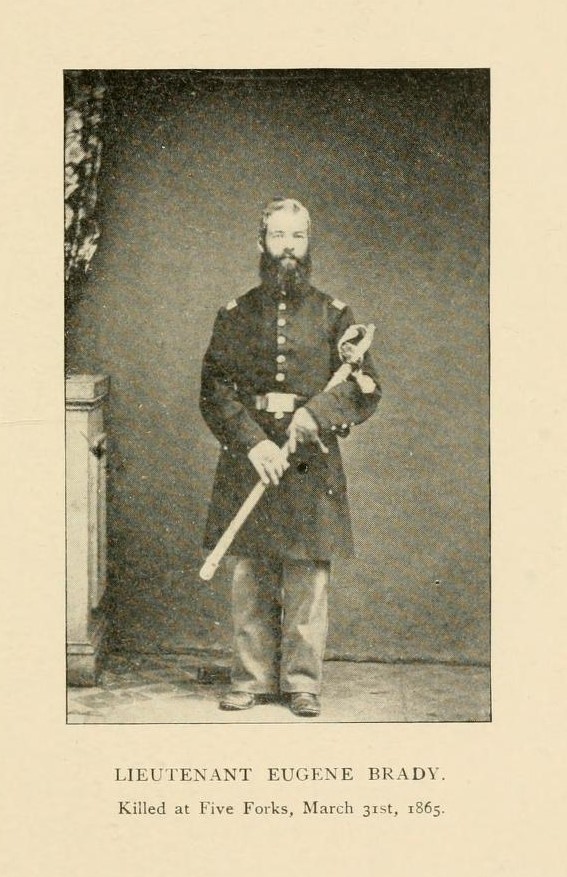

Have you ever wondered about the personal stories behind those sepia-toned photographs of Civil War soldiers? Today, I want to share a story that touched my heart, one that brings to life the courage, sacrifice, and humanity of those who fought in America’s bloodiest conflict. In my hands lies a weathered letter, written by First Lieutenant Eugene Brady of the 116th Pennsylvania. The creases in the letter are witness to countless readings. Like thousands before him, Brady left the emerald shores of Ireland, seeking a new life in America. Instead, he found a nation torn apart by war and a calling that would ultimately lead to his destiny. Brady wasn’t just another officer in the famed Irish Brigade; he was a father, a husband, and a leader who earned the unwavering loyalty of his men. As I unfold this remarkable story of his final days, culminating in a fateful charge that would mark him as one of the last heroes of the Irish Brigade to fall in battle, we’ll discover how one immigrant’s journey became intertwined with America’s destiny.

Brady was born in Ireland circa 1830[1]. Eugene Brady immigrated to the United States to escape the Great Famine. He settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he met Mary Fery. They married on October 18, 1855[2]and their Union resulted in four children. According to the 1860 United States Federal Census, Brady was employed as a police officer.

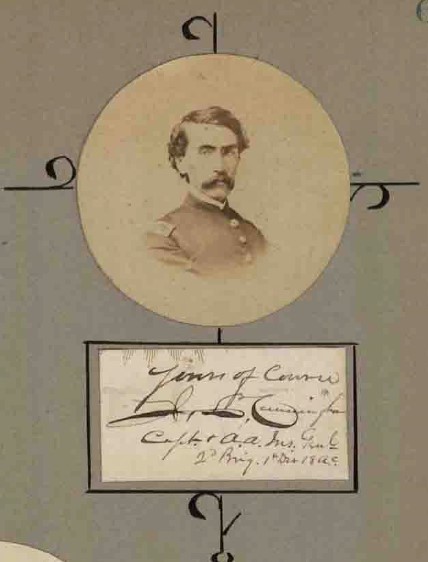

By the summer of 1862, Brady had shifted to a career as a painter, and the nation was embroiled in war. Brady responded to the call to arms, and enlisted on June 11, 1862[3]. He was mustered in as a corporal in Company “K” 116th Pennsylvania Infantry on August 15th, 1862[4].

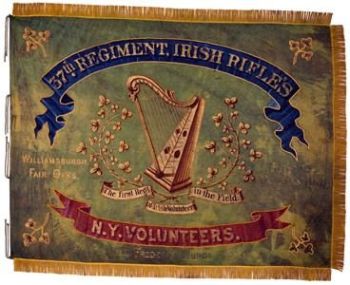

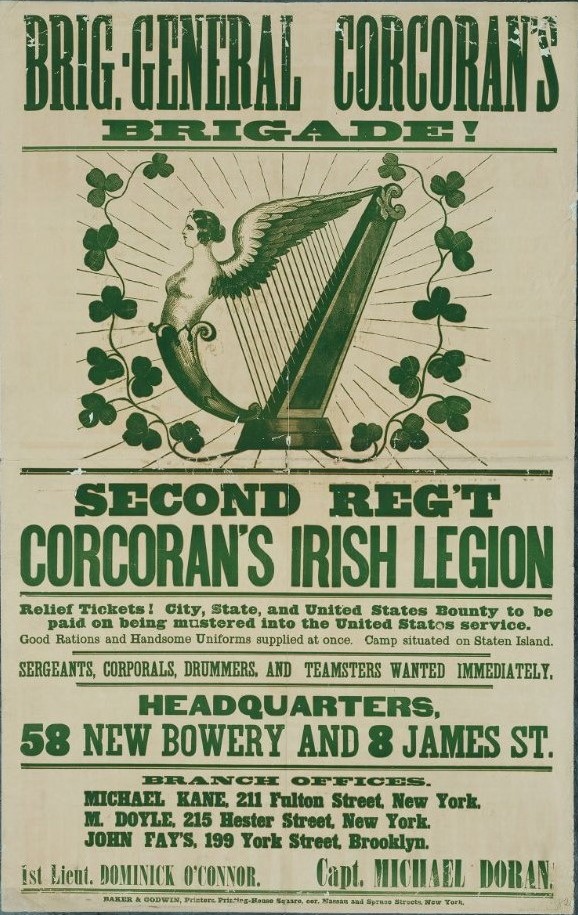

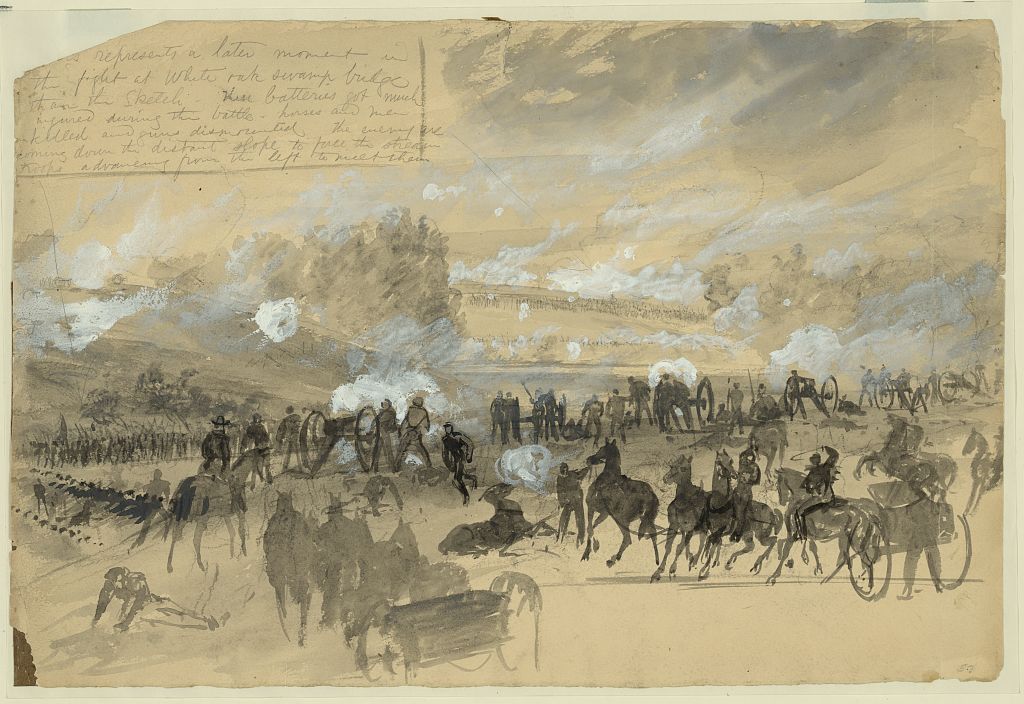

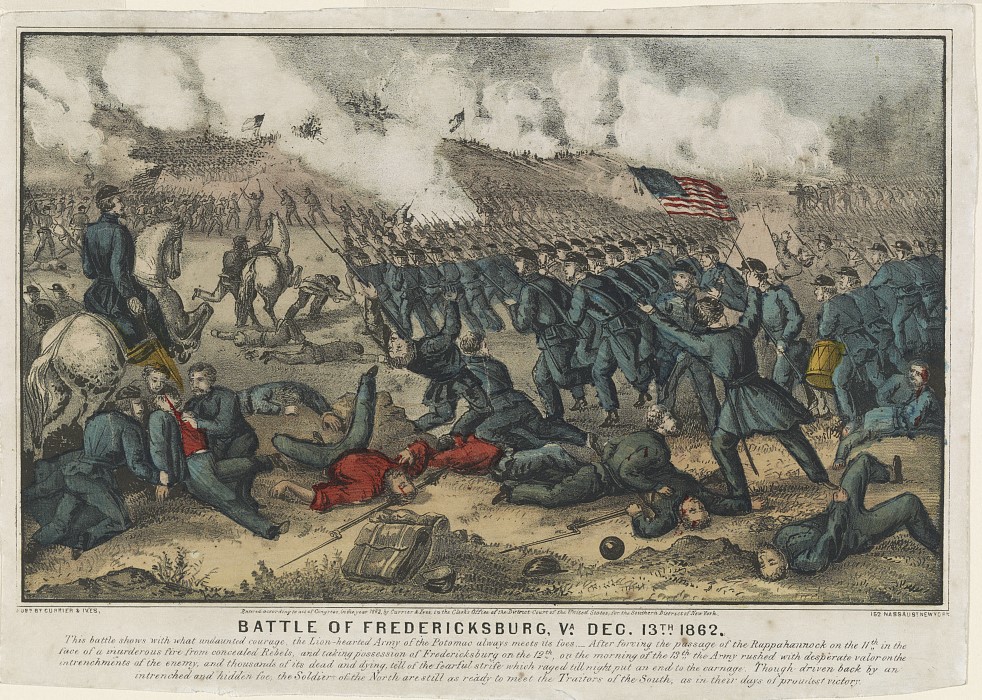

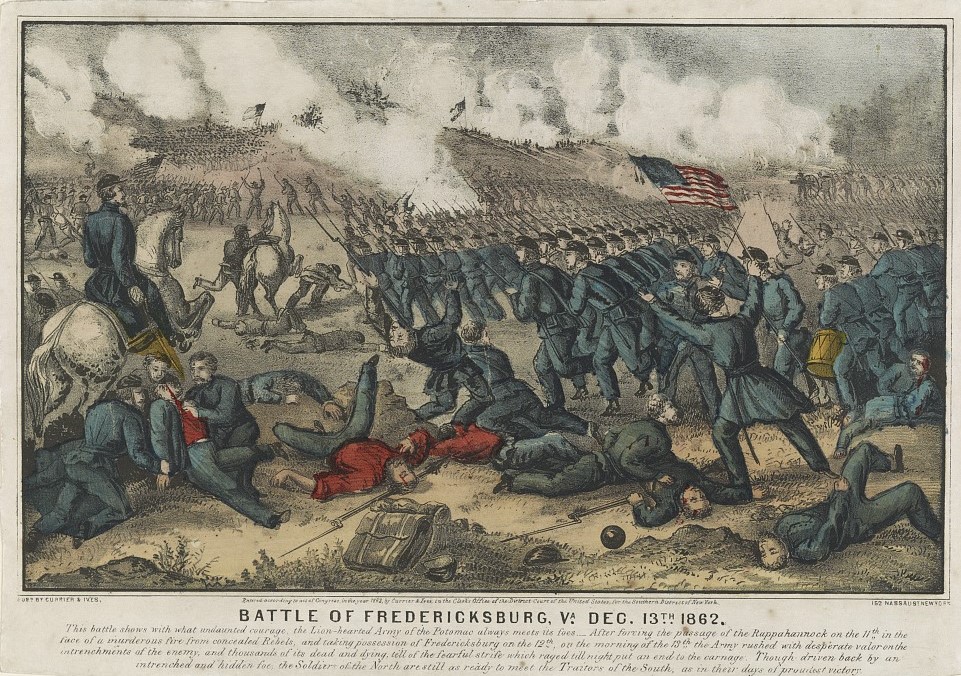

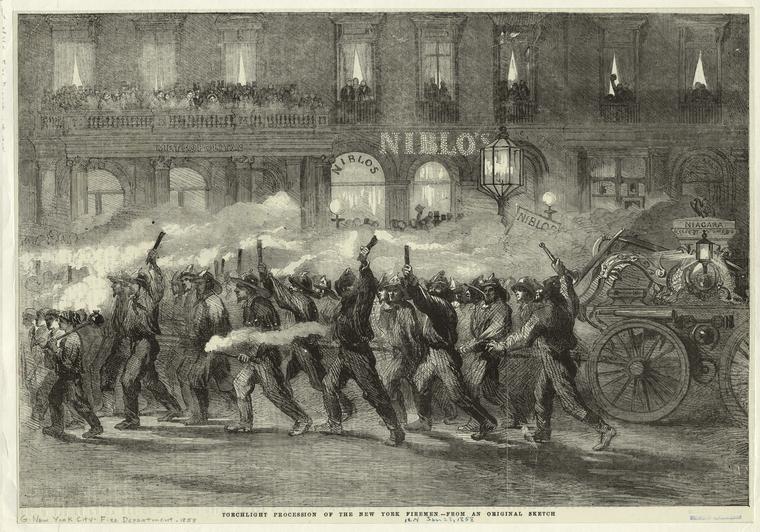

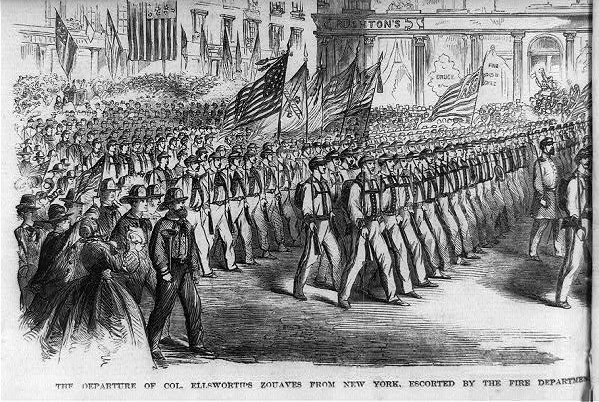

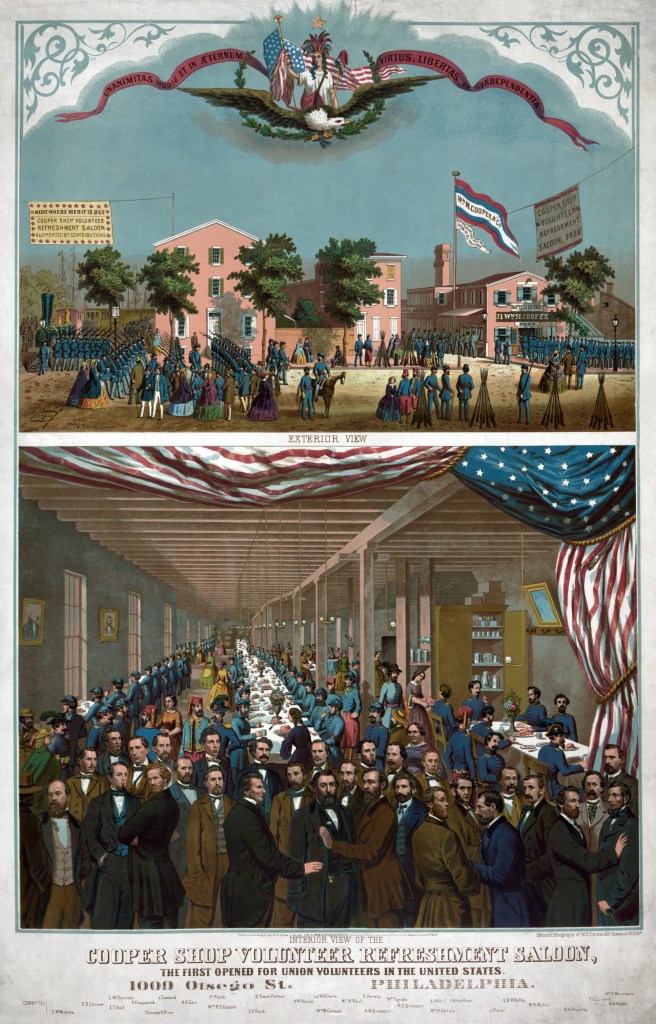

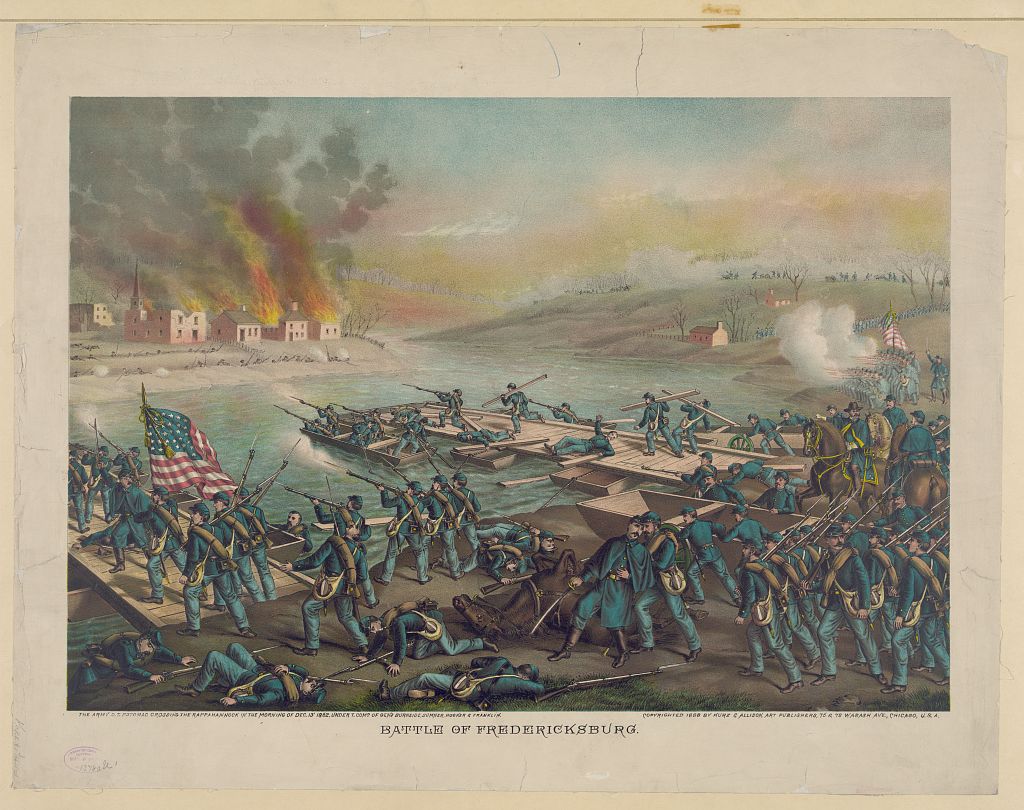

Corporal Brady and the 116th Pennsylvania Infantry embarked on their journey from their home state to Washington, D.C., on August 31. They were marching toward the heart of the conflict. By September 7, they had reached Rockville, Maryland, and then advanced to Fairfax Courthouse. As October arrived, they advanced to Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, where they officially joined the legendary Irish Brigade as part of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, 2nd Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac. From late October through mid-November, Brady and his comrades pressed through the rugged terrain of Loudoun Valley before settling at Falmouth, Virginia. There, they braved the elements and prepared for the battles ahead, camping until mid-December, and unknowingly standing on the precipice of the brutal engagement that awaited them, the Battle of Fredericksburg. Corporal Brady and 116th Pennsylvania had not previously engaged in a significant battle; Fredericksburg would be a brutal initiation. With the Union’s assault losing momentum, the 116th and the remainder of the Division were directed into the fray.

All the soldiers adorned a sprig of green boxwood in their caps to signify their membership in Meagher’s Irish Brigade. In his book, The Story of the 116th Regiment: Pennsylvania Volunteers in the War of Rebellion, Colonel St. Clair Augustine Mulholland details the march into Fredericksburg the day before they engaged in the battle.

“It was a cold, clear day, and when the Regiment filed over the bluffs and began descending the abrupt bank to cross the pontoons into the town, the crash of two hundred guns filled the valley of the Rappahannock with sound and smoke. The color-bearers of the Irish Brigade shook to the breeze their torn and shattered standards:

“That old green flag, that Irish flag, it is but now a tattered rag, but India’s store of precious ore Hath not a gem worth that old flag.”

The Fourteenth Brooklyn (” Beecher’s Pets “) gave the brigade a cheer, and the band of Hawkin’s Zouaves struck up ” Garry Owen ” as it passed. Not so pleasant was the reception of the professional embalmers who, alive to business, thrust their cards into the hands of the men as they went along, said cards being suggestive of an early trip home, nicely boxed up and delivered to loving friends by express, sweet as a nut and in perfect preservation, etc., etc.”[5]

On the morning of December 13, 1862, after a failed attack led by Union General Meade, Corporal Brady and the men of the 116th were called to arms and lined up for battle. These men heard the roar of battle in the distance and watched their wounded comrades march to the rear.

“The wounded went past in great numbers, and the appearance of the dripping blood was not calculated to enthuse the men or cheer them for the first important battle. A German soldier, sitting in a barrow with his legs dangling over the side, was wheeled past. His foot had been shot off, and the blood was flowing from the stump. The man was quietly smoking, and when the barrow would tip to one side, he would remove the pipe from his lips and call out to the comrade who was pushing: “Ach, make right”! It seemed ludicrous, and some of the men smiled, but the sight was too much for one boy in the Regiment, William Dehaven, who sank in the street in a dead faint……..so the Regiment stood — under arms, listening to the sounds of the fight on the left and waiting patiently for their turn to share in the strife, while General Thomas Francis Meagher, mounted and surrounded by his staff, addressed each Regiment of his (the Irish) brigade in burning, eloquent words, beseeching the men to uphold in the coming struggle the military prestige and glory of their native land.”[6]

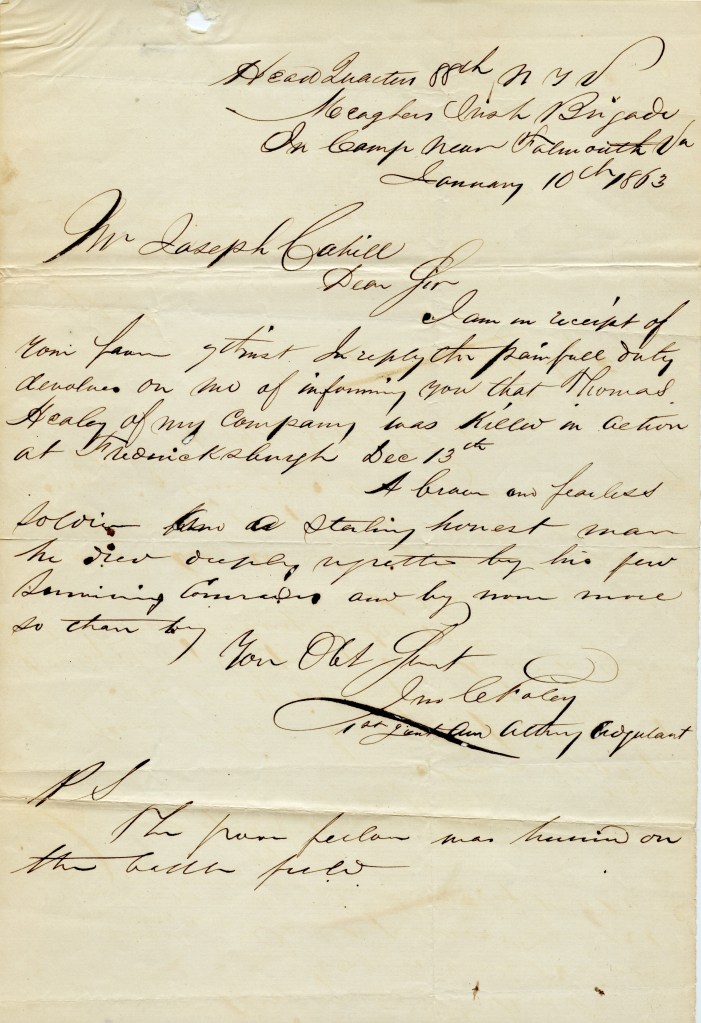

The men of the 116th were sent forward through a deserted city. Soldiers conversed in hushed whispers as exploding shells rained down, causing devastating damage. The first shell severely injured the Colonel, decapitated a Sergeant, and claimed the lives of three others in the 116th. One shell hit the 88th New York, putting 18 soldiers out of action. Despite this devastation, the Regiment continued marching in columns of four, but the bridge they needed to cross had been destroyed. The shells continued to fall, accompanied by Minie balls intertwining with their screeches.

The men faced a challenging situation as they stepped over the broken bridge, stepping on the shattered timbers, while some men plunged into the freezing water. The shells continued to fall, and an officer fell into the stream, mortally wounded. After crossing the stream, a sharp rise in the ground hid the Regiment from the enemy, allowing them to prepare for the column of attack led by the brigade front.

“Then the advance was sounded. The order of the regimental commanders rang out clear on the cold December air, ” Right shoulder, shift arms, Battalion forward, guide centre, march “. The long lines of bayonets glittered in the bright sunlight. No friendly fog hid the Union line from the foe, and as it advanced up the slope, it came in full view of the Army of Northern Virginia. The noonday sun glittered and shone bright on the frozen ground, and all their batteries opened upon the advancing lines. The line of the enemy could be traced by the fringe of blue smoke that quickly appeared along the base of the hills. The men marched into an arc of fire. And what a reception awaited them! Fire in front, on the right and left. Shells came directly and obliquely and dropped down from above. Shells enfiladed the lines, burst in front, in rear, above and behind, shells everywhere. A torrent of shells; a blizzard of shot, shell and fire. The lines passed on steadily. The gaps made were quickly closed. The colors often kissed the ground but were quickly snatched from dead hands and held aloft again by others, who soon in their turn bit the dust. The regimental commanders marched out far in advance of their commands, and they too fell rapidly, but others ran to take their places. Officers and men fell in rapid succession.[7]”

Through this hellish fire, the 116th Pennsylvania, as part of the Irish Brigade, got within thirty yards of the stone wall that was the stronghold of the Confederate position. All the Irish Brigade’s field and staff officers were wounded. The brigade began pouring fire into the Confederate line. One of their color sergeants, waving the flag on the crest, was struck by five balls in succession, piercing the colors and breaking the flagstaff. The command began falling back. The men of the 116th and the rest of the Irish Brigade who were able to move hurried to the rear. Those who were immobilized stayed on the field, many of them for days after the fight. When the fight began, the Regiment marched on the field with 17 commissioned officers and 230 enlisted men. As a result of the battle, 12 officers were wounded, and 77 men were killed, wounded, or missing.[8] This was Corporal Eugene Brady’s first action; he had seen a true baptism by fire. Due to the number of men lost in the Regiment, they were forced to consolidate into a battalion of four companies. Corporal Brady was then promoted to Sergeant and transferred to “D” Company on January 26, 1863.[9]

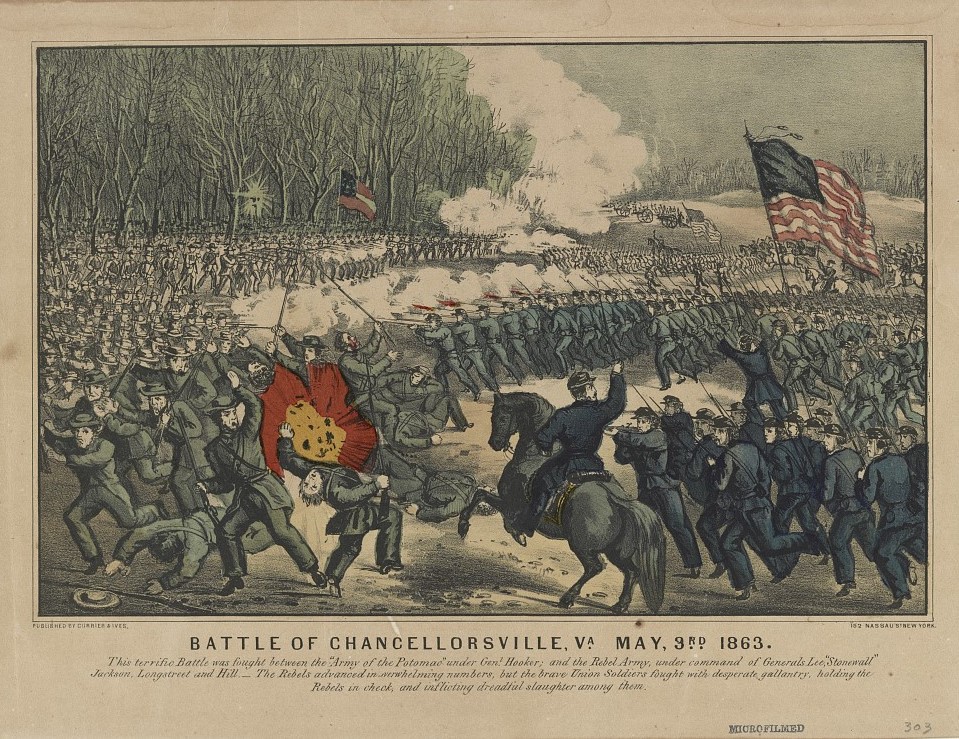

Sergeant Brady and the 116th would set up a winter camp at Falmouth, Virginia. They stayed there until the end of April. Receiving instructions to go toward Chancellorsville, the Regiment then moved out and marched until they reached a swamp, where they set up camp for the night. Col. St. Clair Augustine Mulholland describes the accommodations in his memoir.

“The regimental line ran through a swamp that skirted the edge of a dark wood. The darkness became dense. The ankle-deep ooze made lying down impossible and standing up most inconvenient, so’ fallen trees as roosting places were in great demand, some sitting and trying to balance themselves on a ragged tree stump with feet drawn up to avoid the wet. Watersnakes crawled around in great numbers, frogs croaked, and hundreds of whip-poor-wills filled the trees and made the long night more dismal by their melancholy calling.”[10]

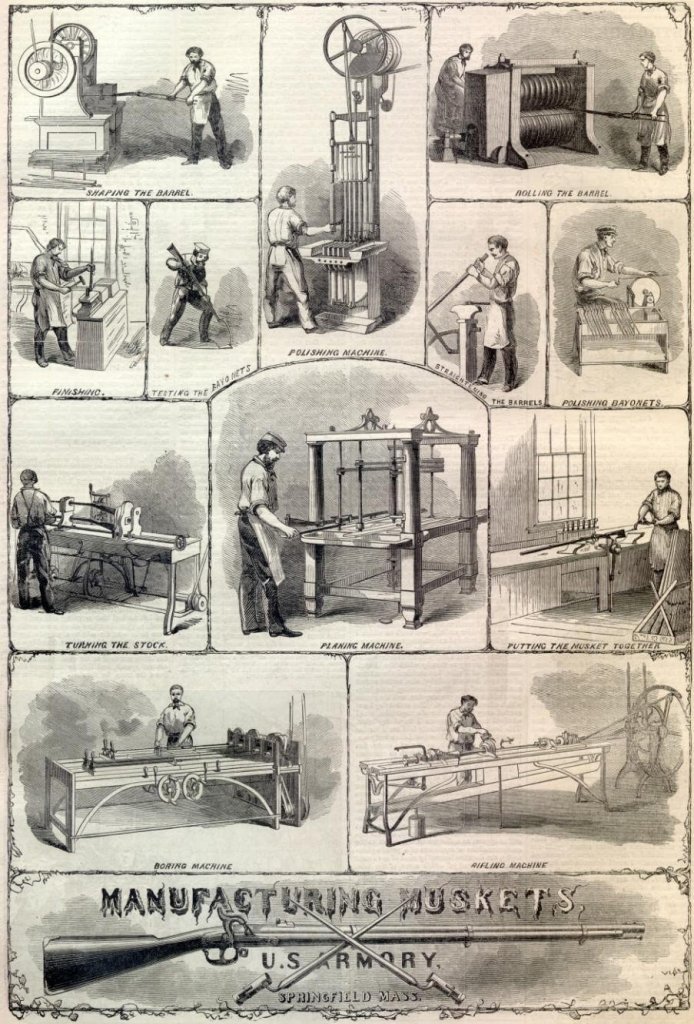

The following day, May 1, the Regiment was positioned with the right, flanking the plank road that extends from Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville and the left, flanking the river. They waited all day for an assault that never came while listening to the distant crash of war. The next day, they were moved to fill a gap on the right flank; here again, they heard the roar of battle as they fixed fortifications and turned all the local structures into blockhouses. Brigadier General Thomas Francis Meagher visited the line in the afternoon to encourage his men. A little later, an officer rushed to the commander to report on the enemy’s progress. Just then, a startled deer fled through the battlefield just before Confederate General Stonewall Jackson’s 26,000 men launched a surprise attack on the Union Army’s right side. The musket fire intensified, and Union soldiers, particularly from the Eleventh Corps, began to panic and retreat in confusion. Some got caught in the abatis (defensive obstacles), while others frantically tried to flee. However, Brady and the 116th Pennsylvania and others in the Irish brigade remained steadfast, blocking and reorganizing the fleeing soldiers.

As dusk fell, the gunfire intensified, and the brigade officers worked to restore order, redirecting troops and preparing for action. A final burst of musketry rang out as night fell, followed by an eerie silence.

Around midmorning on May 3, the 116th received orders to advance toward Chancellorsville House and join the rest of the Division. At the time, part of the Division was already engaged in battle, pushing back the Confederate forces. Once again, Eugene Brady and the men of the 116th marched toward the sound of gunfire, passing streams of the dead and dying as they made their way to their position on the battlefield. Describing the harrowing scene, Colonel St. Clair Augustine Mulholland later wrote.

“As it passed along, the evidence of the struggle soon became manifest. Streams of wounded men flowed to the rear. Men with torn faces, split heads, smashed arms, wounded men assisting their more badly hurt comrades, stretchers bearing to the rear men whose limbs were crushed and mangled, and others who had no limbs at all. Four soldiers carried on two muskets, which they held in form of a litter, the body of their Lieutenant Colonel who had just been killed. The body hung over the muskets, the head and feet limp and dangling, the blood dripping from a ghastly wound — a terrible sight indeed. Wounded men lay all through the woods, and here and there, a dead man rested against a tree, where, in getting back, he had paused to rest and breathed his last. Shells screamed through the trees and, as the Regiment approached the front, the whir of the canister and shrapnel was heard, and musket balls whistled past, but the men in the ranks passed on quietly and cheerfully, many of them exchanging repartee.”[11]

Upon reaching their objective, the men of the 116th quickly took cover along the forest’s edge, pressing themselves to the ground to evade the relentless shell fire. Soon after, Brady and his troops prepared for a desperate stand, determined to repel the enemy while securing a new defensive line. To reinforce their position, the Union commander ordered the Fifth Maine Battery to deploy near the Chancellorsville House, readying for the impending assault. The Battery commander and his men quickly set up their five cannons in an orchard, opening fire on the advancing Confederates. However, the exposed position made them an immediate target for thirty enemy guns. The battlefield became a scene of chaos and destruction, with shells tearing through men, horses, and equipment. The Battery Commander was mortally wounded, followed by the Lieutenant, who was killed moments after taking command. Once filled with blooming apple trees, the orchard was transformed into a fiery, blood-soaked battleground.

Amidst the chaos of battle, an orderly was decapitated by a shell but remained upright on his horse fifty feet before collapsing[12], while another fell with fatal wounds. Soldiers of the 116th suffered gruesome injuries, yet many remained remarkably composed. One such soldier nonchalantly lit his pipe with the burning fuse of an enemy shell while others exchanged jokes, seemingly unfazed by the chaos around them. Within twenty minutes, most of the battery’s guns had fallen silent, nearly all the caissons lay in ruins, and wounded soldiers were strewn across the battlefield.[13] Smoke soon billowed from the Chancellorsville House, now engulfed in flames despite sheltering wounded soldiers and the resident family. Some soldiers of the Union’s Second Delaware bravely rushed to save as many injured as possible, carrying them to safety beneath the trees. As the mansion burned, the women of the household fled onto the porch, where a Union colonel gallantly stepped forward to escort her to safety.

As the battle raged and Union forces withdrew, the 116th was ordered to retrieve the abandoned guns of the Maine Battery. A group of one hundred men from the 116th rushed to grab the field pieces. As a squad struggled to move one of the guns, a shell exploded in their midst, killing two soldiers, wounding several others, and knocking everyone to the ground.[14] Undeterred, the men quickly got back on their feet, laughing off the blast, and resumed their efforts, successfully hauling the gun away. A Sergeant from the 116th spotted an abandoned caisson and was determined to save it. Realizing he was alone and unable to haul it away, he made a quick decision to destroy it instead. “Standing, [he] wished to take it off also, but the men were gone, and, as he could not haul it off alone, he concluded to destroy it; so striking a match, he lit a newspaper, threw it in, jumped back, and the chest blew up. By some miracle, the brave boy remained uninjured himself.”[15]

With the guns secured, the Regiment went down the road as Confederate forces advanced, taking control of Chancellorsville. Brady, along with the 116th, was the last to leave the battlefield. Upon emerging from the woods near the Bullock House, the regiment was met by General Sickles, who, “rising in his stirrups, called for three cheers ‘for the Regiment that saved the guns’”[16] filling the exhausted soldiers with a sense of pride and accomplishment.

As the Union army withdrew to its defensive line, the Battle of Chancellorsville ended with only a brief skirmish. Although large-scale fighting ceased, Confederate sharpshooters remained active, making any movement dangerous. Eventually, the Union forces, defeated, began their retreat across the river. Through the night, they moved silently under the cover of darkness as the wind howled through the trees and occasional gunfire echoed in the distance. With no time to retrieve the wounded or bury the dead, fallen soldiers remained on the battlefield as the Union army withdrew. Most had crossed the swollen river by dawn, with the 116th among the last to retreat. As the Union pickets rushed to the bridge, Confederate forces attempted to cut them off, but they escaped just in time. Once across, the pontoons were severed, and a Confederate battery fired a few final shots as the last Union troops disappeared, bringing the Chancellorsville campaign to an end.

Sergeant Brady and the 116th underwent relentless drills, reviews, and inspections as May progressed, achieving peak discipline and proficiency, particularly in bayonet exercises and skirmishing. Life in the camp was nonstop, from reveille to taps, making picket duty along the serene river the most coveted assignment. Unlike the harsh winter months, when soldiers endured freezing temperatures without fires, May brought warmth and beauty, with daisies and buttercups lining the riverbanks. Standing watch for two hours, followed by four hours of rest, was far preferable to the constant demands of camp life, where drills and inspections left little time for respite.

With the 116th Regiment, Brady embarked on a grueling march that began on June 14, enduring extreme heat, exhaustion, and treacherous conditions as they moved through Virginia and into Maryland. Along the way, they faced hardships such as limited water, stifling dust, and even an unsettling encounter with a mass of snakes during a nighttime swim. They passed historic battlefields, including Bull Run, and faced Confederate resistance at Haymarket. Despite the exhausting pace, the soldiers found moments of relief, particularly in Frederick, Maryland, where they enjoyed fresh food and the comforts of the city. The Regiment then pushed forward, crossing into Pennsylvania with renewed spirits and covering an incredible 34 miles in one day. By July 1, they reached the outskirts of Gettysburg and prepared for the battle that would soon unfold.

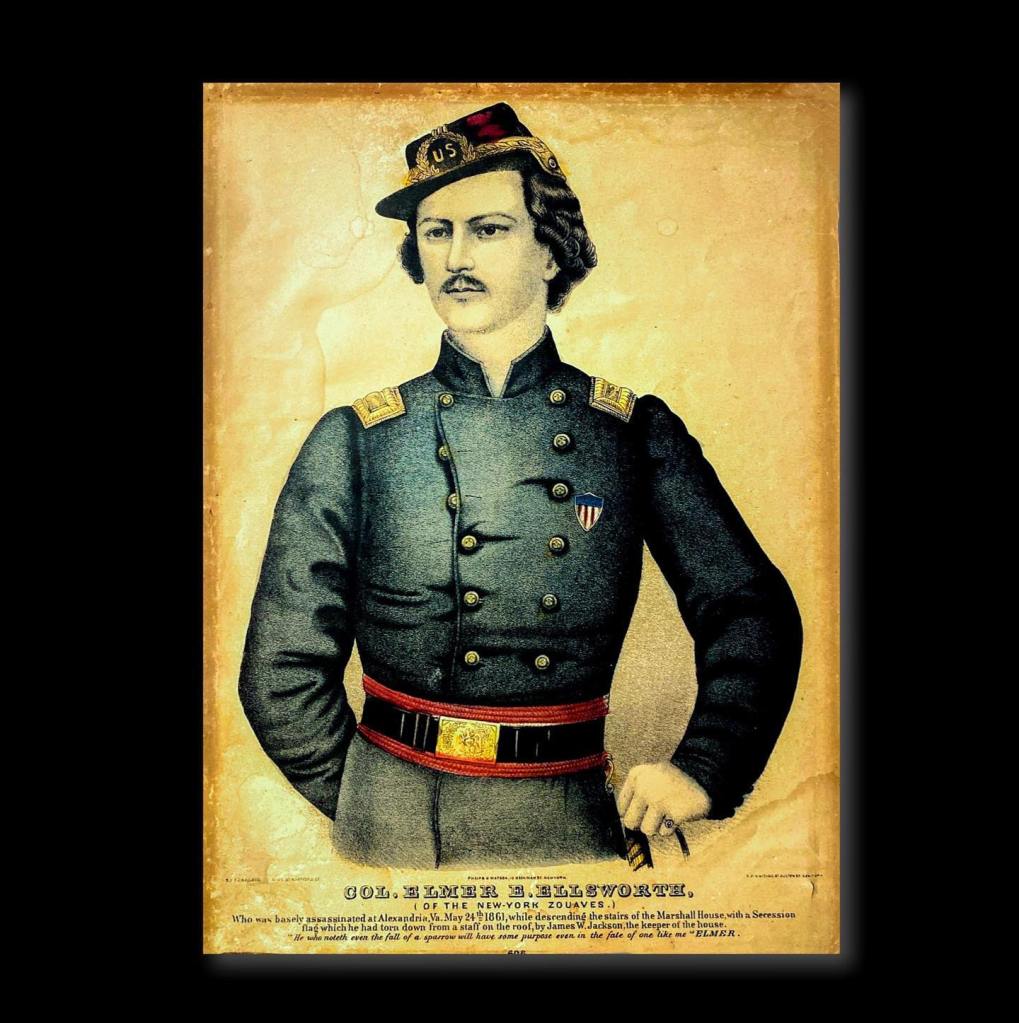

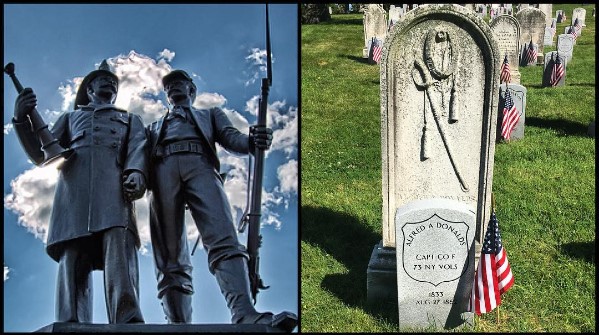

As the afternoon sun hung low on July 2nd, orders were given for the Irish Brigade to advance into battle. But before they marched into the chaos of Gettysburg, the soldiers took part in one of the most profound and solemn moments ever witnessed on an American battlefield.

Father William Corby, the brigade’s chaplain, stood atop a large rock before Brady and the assembled men of the 116th, who stood in silent formation, awaiting their fate. Knowing the bloodshed that lay ahead, Father Corby offered them general absolution, a sacred rite rarely seen outside of European battlefields. With heads bowed and knees in the dirt, the soldiers received his blessing as he extended his hand over them, his voice carrying the ancient Latin words of forgiveness:

“Dominus noster Jesus Christus vos absolvat…”[17]

The moment was breathtaking. Even as the roar of cannon fire and the rattle of musketry echoed from the distant Peach Orchard and Little Round Top, an eerie stillness fell over the brigade. Nearby, a general and his officers watched in silent reverence. The absolution was not just a prayer; it was a farewell. Dressed in their uniforms, these men were already clad in their burial shrouds. Within the hour, many of them would fall, their final act on earth a whispered prayer beneath the Pennsylvania sky.

Soon after this moment of peace, the Regiment advanced along the ground where other men had bravely fought and fallen, pushing beyond their last position to engage the enemy. With one Union General mortally wounded and his men forced to withdraw after a valiant struggle, the Irish brigade surged forward to renew the assault. Positioned at their extreme right flank, the 116th played a crucial role in anchoring the line as the battle raged.

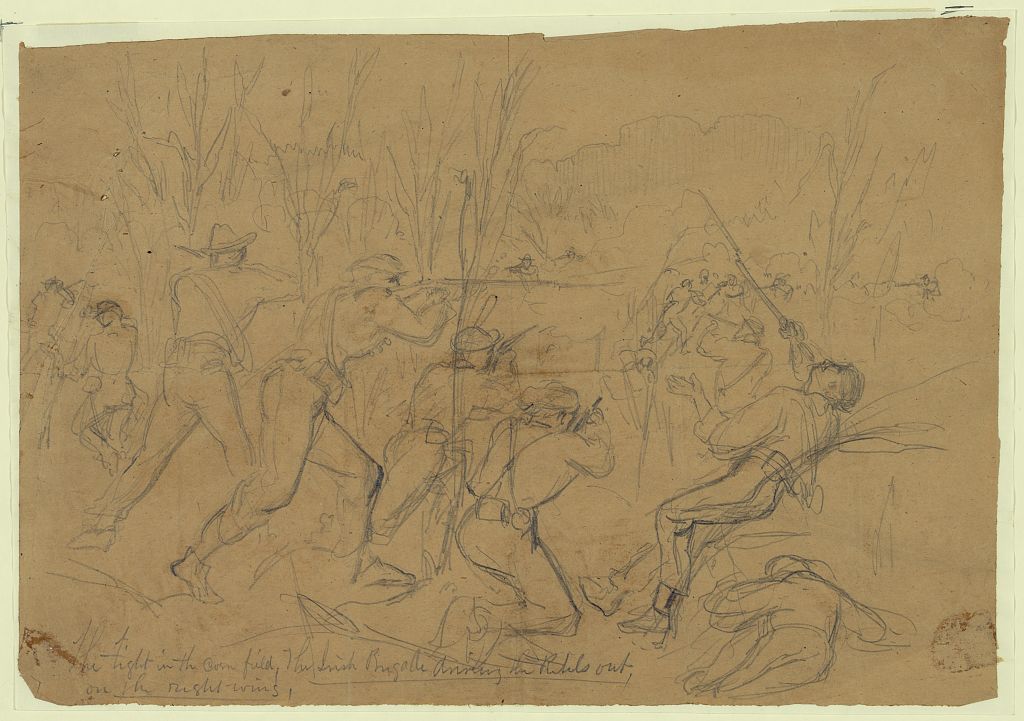

Brady and the regiment advanced with disciplined precision, navigating the rugged terrain of boulders and trees. They held their formation despite the challenging landscape. Nearing the crest, they encountered the enemy and were met with a volley of fire—fortunately, aimed too high to inflict significant damage. Undeterred, the men surged forward, engaging in brutal close combat. “The men of the Regiment went in at a ‘right shoulder shift’ and, although the ground was covered with huge boulders, interspersed with forest trees, hilly and rough, the alignment was well preserved and, as it neared the crest, met the enemy and received a volley.[18].” Officers drew their revolvers, and fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued. A sergeant standing tall and fearless in the fray was tragically struck down by a bullet to the brain. However, the Confederates, exhausted and overwhelmed, ultimately surrendered and were sent to the rear as prisoners of war.

The 116th halted where their monument now stands. Here, they unexpectedly encountered Confederate forces at the crest of a hill. The Confederates fired too quickly, causing most of their shots to miss, while the Regiment’s return fire was devastating, leaving the enemy’s position covered in their dead. The Regiment then observed Confederate forces preparing another attack, and as orders were given to retreat, they withdrew in good order toward Little Round Top. Some soldiers from the 116th regiment were captured. The retreat through a wheat field was chaotic and deadly, with several men missing or killed. The Regiment eventually reformed near Cemetery Ridge, where it held its position as night fell over the battlefield. One of the men wounded during the day’s action was Sergeant Eugene Brady.

After the battle, as Sergeant Brady was recovering from his wound, he received a well-earned promotion to First Lieutenant on November 21, 1863[19]. He would rejoin the 116th shortly after, ready to return to the fight.

On November 25th, First Lieutenant Brady and the 116th Regiment left camp and entered the Mine Run campaign. After crossing the Rapidan at Germania Ford, they fortified positions at Robertson’s Tavern but saw no immediate combat. On November 27, they took their position in the woods near Mine Run. On November 28, amidst heavy rain, the Regiment moved closer to the front, preparing for an attack. The Union planned to turn the Confederate right flank. That night, 16,000 troops, including the 116th, marched through rugged terrain. By sundown on the 29th, the Union forces reached their position. The 116th engaged the enemy, pushing them into their entrenchments, but darkness halted further action.

That night was bitterly cold, with soaked and exhausted soldiers suffering immensely; more lives were lost to exposure than in some battles. As dawn broke, the men braced for battle, but no order to attack came, leaving them in a state of tense anticipation.

Nearly the entire 116th Regiment was assigned to the skirmish line during the Battle of Mine Run, leaving only a small guard with the colors. During the fight, Brady and the men of the 116th captured many Confederate prisoners. The captured men were primarily young men from North Carolina, who were poorly clothed and equipped; some even seemed relieved to be taken prisoner.

The 116th camped and reorganized over the next few months. On May 1, 1864, a fierce storm swept through the camp at Brandy Station, toppling tents and wrecking winter quarters. Soldiers scrambled to make repairs, but orders came to move before the work was complete. Then, on May 2, an eerie calm settled over the army; there were no drills, reviews, or duties. It was a moment of quiet before the storm as the soldiers braced for the campaign ahead.

As night fell on May 3, Brady and the 116th silently broke camp, leaving fires burning to deceive the enemy. Moving stealthily through dense forests, they crossed the Rapidan at Ely’s Ford. By noon on May 4, they reached the ruins of the Chancellorsville House, where they massed. Pickets were posted, artillery positioned, and arms stacked; every soldier was accounted for as they prepared for the battles to come.

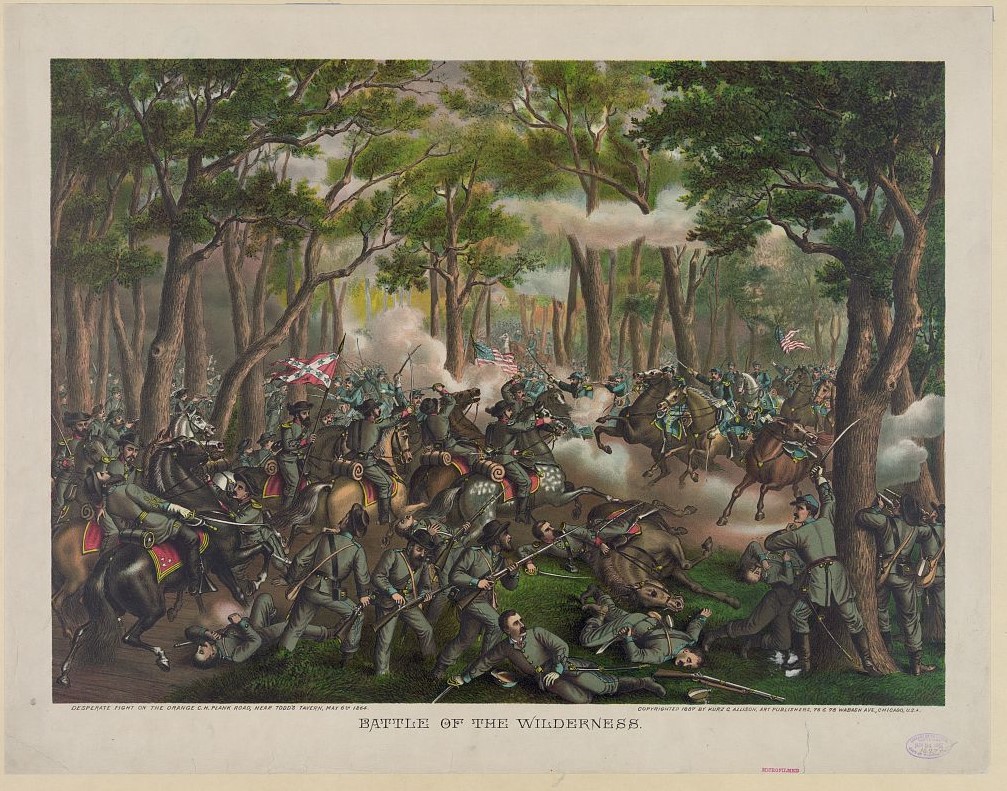

On the afternoon of May 5, Brady and the 116th found themselves in a nearly impenetrable wilderness, surrounded by dense woods that concealed the enemy. Though they could not see their foes, the eerie sound of whistling bullets cutting through the trees betrayed their presence.

In hushed preparation, Brady and his men readied for battle. Advancing in formation proved nearly impossible, as the thick underbrush obscured visibility, even within their ranks. Yet, despite the chaos of the terrain, the men pressed on into the unknown, bracing for the clash ahead. As the leading regiment pushed forward, it collided with the enemy after advancing just three hundred yards. A sudden eruption of musket fire shattered the silence; the brutal campaign of 1864 had begun. The battlefield lay just beyond the remnants of abandoned gold mines, where decaying timbers from old cabins lay scattered and deep mining shafts punctuated the dense wilderness.

The battlefield became a scene of chaos and carnage as First Lieutenant Brady and the Regiment pressed forward through the thick smoke and relentless gunfire. Bullets tore through the dense underbrush, cutting down men in their ranks, yet the soldiers pushed on with unwavering determination. Even amid the horror, the camaraderie and dark humor of the troops shone through, as captured in this account:

“The crash of musketry filled the woods; the smoke lingered and clung to the trees and underbrush and obscured everything. Men fell on every side, but still, the Regiment passed steadily on. One by one, the boys fell—some to rise no more, others badly wounded—but not a groan or complaint, and a broad smile passed along the line when Sergeant John Cassidy of Company E, finding fault because when shot through the lungs, he had to walk off without assistance, someone said to him: “Why, Cassidy, there’s a man with all of his head blown off, and he is not making half as much fuss as you are!”[20]‘

Soon after the opening salvo, the 116th Regiment was temporarily detached from the Irish Brigade to support another Brigade. As Brady and the 116th marched back to rejoin their unit at dusk, they noticed a critical gap in the battle line. Without waiting for orders, they swiftly moved in to fill the breach, providing essential reinforcement at a pivotal moment. Their quick thinking and decisive action were crucial in stabilizing the line.

As the Confederate forces advanced toward the opening in the battle line, the 116th Regiment, with their disciplined ranks, stopped the enemy in its tracks. After a brief exchange of gunfire, the Confederates withdrew just as another Union regiment arrived with resounding cheers to reinforce the position. As darkness fell, Brady and the exhausted soldiers, hungry and worn from battle, lay down to sleep without supper. Throughout the night, stretcher-bearers carried the wounded to the rear, and with the first light of morning, the line withdrew once more.

This fight would be forever known as The Battle of the Wilderness.

The following day, First Lieutenant Brady and his Regiment held their position along the road while the rest of the Union Army advanced into the woods. Initially, they heard the cheers of their advancing troops, but by noon, the tide turned, and the wounded began pouring back, signaling a Union setback. The enemy launched an attack in the evening, and a fierce firefight ensued. As the battle raged, the Regiment faced relentless enemy fire and an unexpected, terrifying new threat: flames engulfing the battlefield. The intense heat and thick smoke turned the fight into a nightmarish scene, yet the soldiers stood their ground with unwavering determination:

“The wind fanned the flames, and soon, the whole line in front of the Regiment was in a blaze. The smoke rolled back in clouds; the flames leaped ten and fifteen feet high, rolled back, and scorched the men until the heat became unbearable, the musket balls the while whistling and screaming through the smoke and fire. A scene of terror and wild dismay, but no man in the ranks of the Regiment moved an inch. Right in the smoke and fire, they stood and sent back the deadly volleys until the enemy gave up the effort and fell back and disappeared into the depths of that sad forest where thousands lay dead and dying.”[21]

The horror of the moment was only heightened when the fire spread to the surrounding trees and brush, consuming the very ground on which so many had fought and fallen. The full extent of the tragedy remained unknown, as many wounded soldiers were trapped in the blaze, their fate left to the mercy of the flames. Yet, in the face of such devastation, acts of bravery emerged. Volunteers, led by a Lieutenant, rushed into the inferno to save as many as possible, exemplifying the selflessness and heroism that defined these soldiers in the darkest times. The enemy’s final assault on the evening of May 6 effectively ended the Battle of the Wilderness. With the 116th, Brady held their position along the road throughout the night and the following day, engaging only in sporadic picket fire and dodging occasional artillery exchanges.

Brady, with the 116th, remained engaged in battle throughout May 8th-10th, 1864, as they maneuvered across the Po River in an attempt to turn the Confederate flank. Initially tasked with capturing a wagon train, the operation evolved into a more significant strategic movement. As Union forces crossed the river, Confederate troops quickly fortified their positions, making an assault infeasible. After a series of skirmishes and near captures, including two of their officers accidentally wandering into enemy lines, the order was given to withdraw. However, as the troops fell back, they were attacked by Confederate forces, resulting in fierce combat amid a burning forest. Despite being surrounded by flames and heavy enemy fire, the 116th held its ground until the last moment before retreating across the final remaining bridge. Tragically, thirty men were left behind, trapped in the blaze. As darkness fell, exhausted but determined, the Regiment rallied once more for another counterattack, bringing what would be known as the Battle of the Po to a close.

On May 11, after a day of picket firing, Brady and the soldiers of the 116th endured a cold, rainy evening with weak fires that barely provided warmth. The harsh wind and pervasive smoke made the conditions nearly unbearable. They managed to boil coffee, but they could not cook a proper meal. Exhausted and soaked, the men settled in for a restless sleep. However, they quickly roused themselves as orders came in around 9 p.m. to march immediately.

At 10 p.m., First Lieutenant Brady and the Regiment were sent on a grueling night march through dense woods, torrential rain, and muddy terrain toward Spottsylvania, with orders to attack at daylight. After midnight, the Regiment arrived at the designated area, forming a double column despite the heavy fog and lingering darkness. An hour later, as the attack began, a Confederate volley killed a high-ranking officer, but the Union soldiers pressed on, launching a surprise assault on the enemy’s works. Brady and the 116th were among the first to breach the enemy defenses, with their regimental colors leading the way, as individual soldiers engaged one-on-one across the contested ground. In the ensuing chaotic combat, the attackers overwhelmed the Confederate defenses, capturing colors, artillery, officers, and thousands of prisoners, thus securing a decisive victory despite the disarray and confusion of battle. The following excerpt vividly illustrates the fierce and personal nature of the combat experienced by the 116th Regiment during the assault :

“Lieutenant Fraley, of Company F, ran a Confederate color-bearer through with his sword; a Confederate shot one of the men when almost within touch of his musket, then threw down his piece and called out, ‘I surrender,’ but Dan Crawford, of Company K, shot him dead; Billy Hager, of the same company, ran into a group of half a dozen and demanded their surrender, saying ‘Throw down your arms, quick now, or I’ll stick my bayonet into you,’ and they obeyed. Henry J. Bell, known as ‘Blinky Bell,’ leaped over the works and yelled, ‘Look out, throw down your arms; we run this machine now.’ A large number of the men of the Regiment ran forward and took possession of a battery of brass pieces and, turning them around, got ready to open on any force that might appear. “[22]

This passage captures the raw brutality of the fighting, the individual acts of valor, and the quick thinking that contributed to the Regiment’s overall success in battle.

The 116th fought in brutal, close-quarters combat on May 12, 1864, during the battle of Spottsylvania Court House, one of the bloodiest days of the war. Scattered along the captured works, they regrouped into squads to face relentless, all-day Confederate assaults that continued into the night. Despite drenching rain, intense hand-to-hand fighting erupted over a mile of trench, with soldiers exchanging musket fire and bayonet attacks. The battle was so fierce that the dead piled up on both sides, and bodies had to be repeatedly cleared from the trenches to make room for the living. Trees were torn apart during the battle, and one large tree fell, injuring some men. The continuous fighting on May 12 left the 116th Regiment scattered after their early charge, preventing them from regrouping immediately. When the fighting finally ceased at midnight and the Confederates retreated, amid a chilling rain, the Union forces took possession of the bloody field.

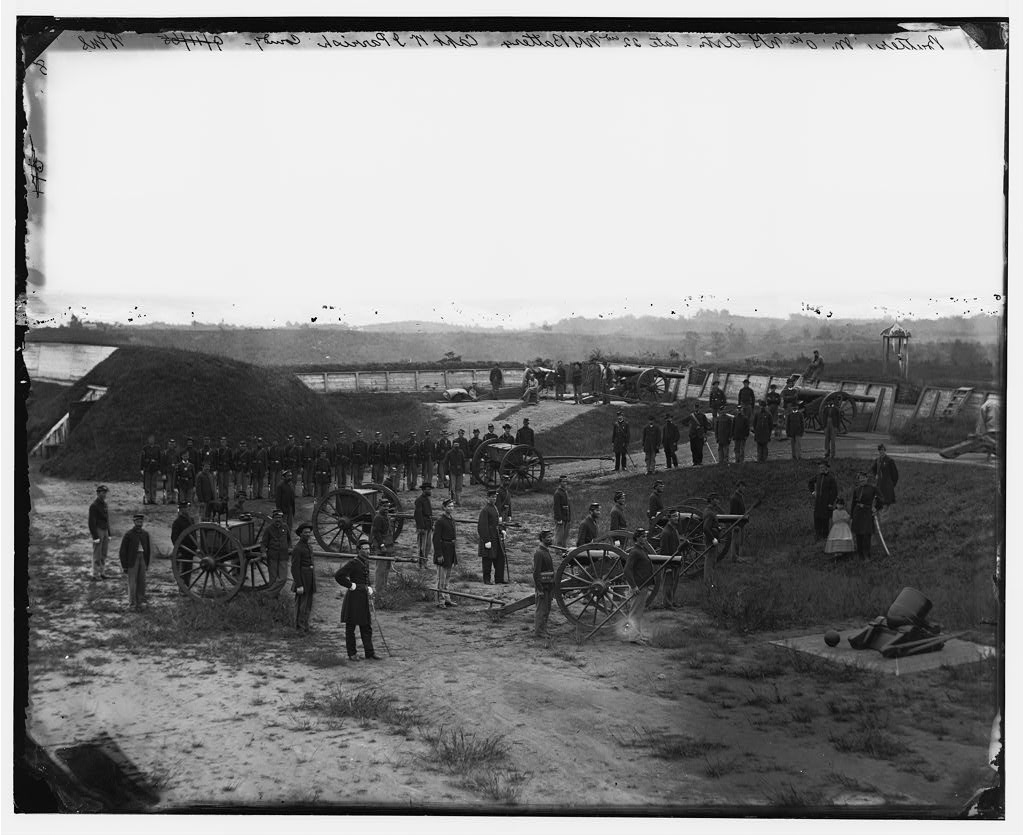

. Virginia, ca. 1888. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/91721595/.

At dawn on May 13, the 116th reassembled the companies and discovered that many brave soldiers had perished during the long, bloody day. Soon, both armies’ exhausted troops finally fell asleep among the dead.

Brady and the 116th would endure continuous marching and skirmishing for the next eleven days, facing enemy fire nearly daily. After a grueling night march on June 1, the Regiment finally settled outside Cold Harbor.

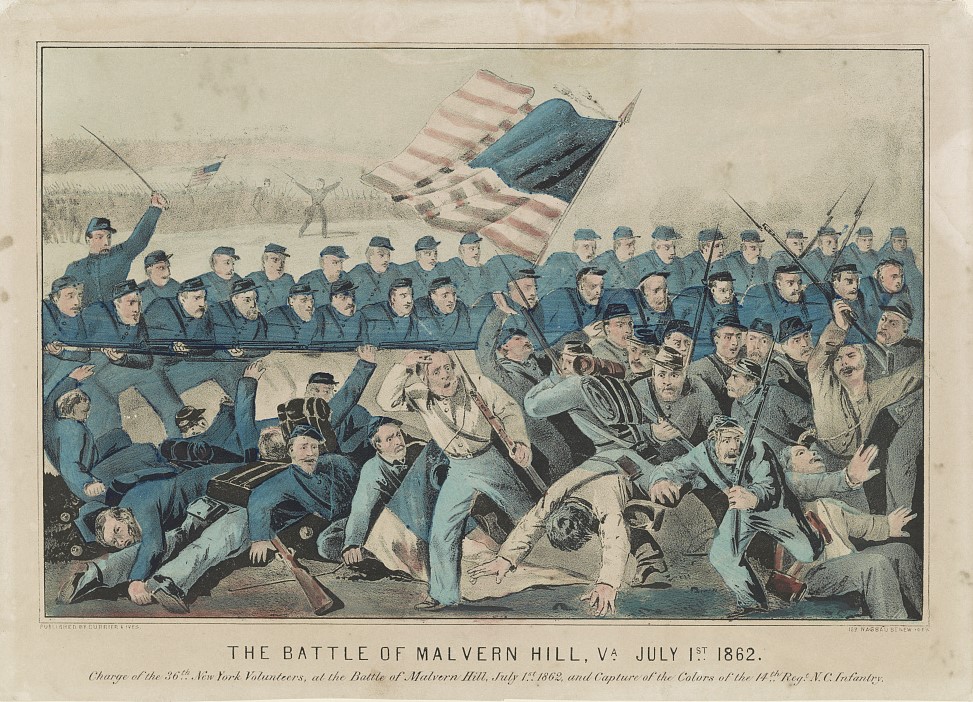

The Battle of Cold Harbor began at 4:30 a.m. with an advance by the Union. The Union troops were met with a devastating Confederate fire, causing heavy losses. Despite the intense resistance, they managed to drive the Confederates from a sunken road and capture 300 prisoners, a battle flag, and artillery.[23].

However, the initial success quickly turned into a disastrous defeat as Confederate reinforcements forced the Union troops to retreat under relentless musketry and artillery fire.

Brady and the 116th were ordered to take cover in a ravine but later had to withdraw under heavy fire, suffering significant casualties while retreating uphill without shelter. Despite the chaos, officers showed bravery in regrouping the troops under fire. The entire battle lasted less than an hour but was one of the bloodiest of the war, with massive Union losses. During the Battle of Cold Harbor, the 116th suffered heavy casualties, losing seventy men and officers who were either killed or wounded.[24]

Brady and the regiment remained stationed at Cold Harbor until the night of June 12, enduring continuous hardship without rest, day or night. There was never a moment of peace from the 3 p.m. roll call until nightfall. The Regiment frequently provided significant picket details, with no relief from the skirmish line until after dark the following night. Soldiers had to find cover and dig makeshift shelters as the opposing lines were incredibly close—sometimes just a few feet apart. In one instance, surprised by his mistake, a Confederate lieutenant unknowingly walked into the 116th’s position and was captured.

On the evening of June 12, the army quietly withdrew from Cold Harbor and began moving left, with the Regiment marching throughout the night.

Lieutenant Brady and the 116th were under fire for nineteen out of thirty-one days, engaging in battles across multiple locations, including the Wilderness, Spottsylvania, North Anna, and Cold Harbor. They faced relentless combat, resulting in over two hundred killed and wounded. This number does not include Company B, which was stationed at division headquarters as provost guard, nor those sent to the rear due to illness, many of whom succumbed to disease from the harsh conditions of constant fighting and exposure.

On the evening of June 13, upon reaching the north bank of the James River, the 116th immediately began digging defensive works despite their exhaustion. Once the fortifications were completed, they were finally able to rest. The following day, June 14, the Union began crossing to the south side of the river, but due to limited transportation, Brady and the regiment could not cross until the evening.

On the afternoon of June 16, the 116th launched an assault on heavily fortified Confederate positions, despite the enemy having reinforced their defenses the night before. The attack was met with intense artillery and musket fire as they advanced over broken ground. Maintaining their formation under heavy fire, the troops charged through abatis and over the enemy’s works before securing the position, engaging in fierce hand-to-hand combat with bayonets. The victory resulted in capturing several Redans, artillery, and prisoners. The 116th suffered heavy losses; 46 enlisted men were killed, wounded, or missing.[25]

Between June 17 and June 21, Brady and the Regiment were heavily engaged in assaults on enemy positions near Petersburg. On June 17, they advanced with near-perfect alignment but suffered heavy losses upon encountering enemy earthworks. The following day, another assault on enemy lines resulted in a bloody repulse, marking the shift to siege warfare.

On June 19, Brady and the Regiment remained under arms, repelling a night attack. They were placed in reserve the next day but remained in heavy combat conditions. On June 21, after a promised rest, they moved toward Reams Station, engaged in a skirmish, and fortified their position. However, a gap in the lines allowed a Confederate cavalry raid, disrupting the support units.

During June and July, the siege of Petersburg intensified, with Union and Confederate forces relying heavily on trench warfare and artillery. Brady and the 116th rapidly constructed redoubts, siege batteries, and defensive structures while introducing devastating mortar fire that surprised the Confederates. However, the Confederates quickly adapted, building bomb-proof shelters and launching their mortar attacks.

The mortar barrages were especially deadly, as multiple shells were fired simultaneously, making it nearly impossible to avoid them. Soldiers on the picket lines and reserves suffered heavy casualties, and even those in supposedly secure camps were at risk. The unpredictability of the mortar fire made it a particularly demoralizing aspect of the siege, as soldiers were uncertain whether they would survive the night. Both sides endured significant losses, making the siege an exhausting and terrifying ordeal.

On the afternoon of July 26, the 116th, along with Lieutenant Brady, departed from camp and marched toward Point of Rocks. Crossing the Appomattox River on a pontoon bridge after dark, the Regiment continued its march through the night. Despite the darkness and warm conditions, small fires helped guide the way. By early morning on July 27, Lieutenant Brady and the 116th reached the James River and crossed on pontoons, massing in the woods until daylight. At first light, the 116th advanced. As the Regiment advanced across the open plain, it encountered heavy enemy fire but managed to reach the Confederate works with minimal losses. The intensity of the enemy’s fire was mitigated by the support of Union gunboats, which launched massive hundred-pound shells over the soldiers’ heads and into the enemy’s fortifications. The sheer power of these shells was awe-inspiring as they exploded with immense force, shredding massive trees and wreaking havoc within the enemy’s lines.

On the night of July 29, under the cover of darkness, Brady and the Regiment began its march back to Petersburg, arriving just in time to witness what would be known as the Battle of the Crater. This disastrous failure resulted in the loss of many Union soldiers. After returning to camp, the Regiment was granted a much-needed two-week rest. However, picket duty remained constant, and casualties on the outer lines continued to occur regularly.

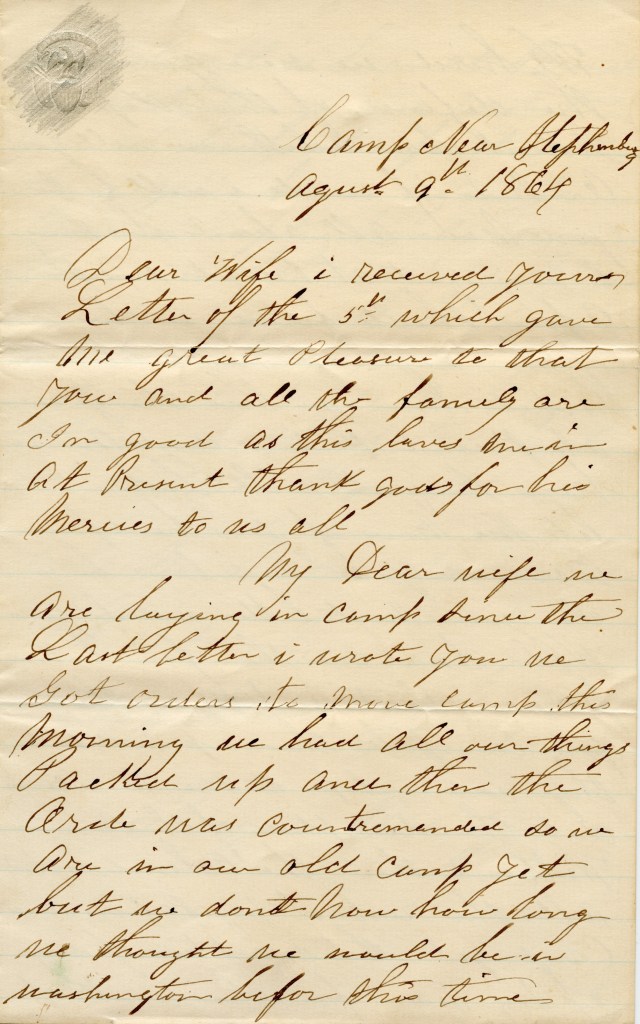

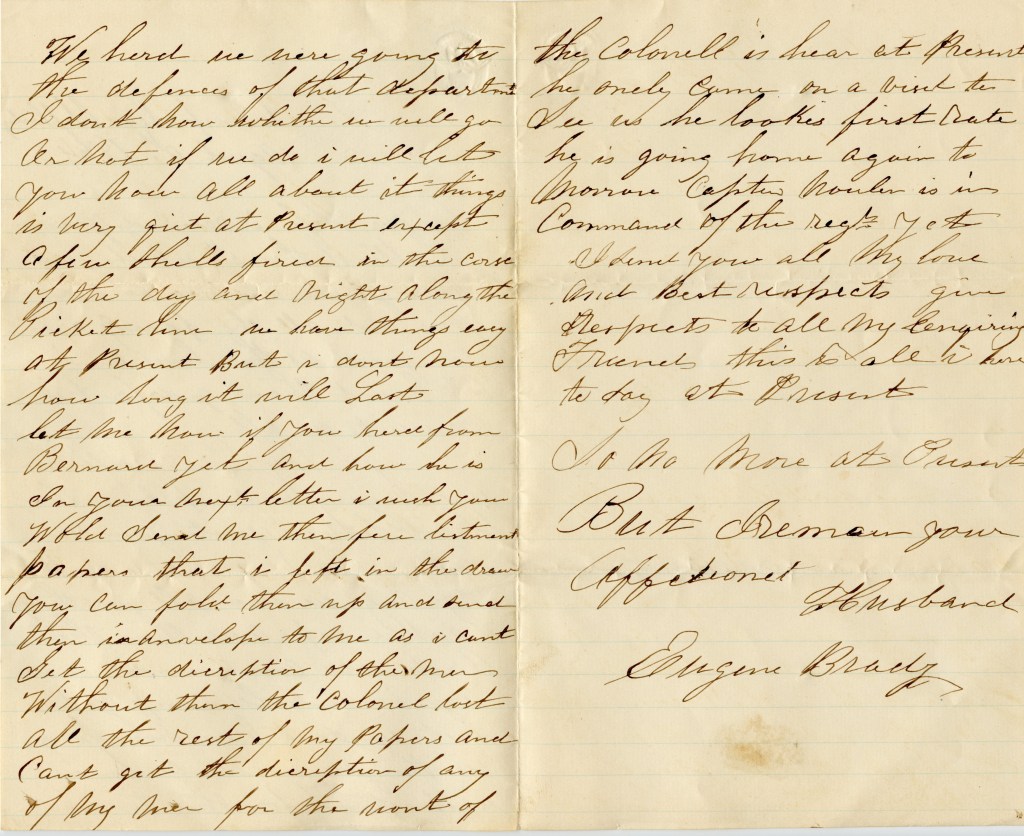

During the Regiment’s brief rest period near Stephensburg in early August 1864, Lieutenant Eugene Brady wrote a heartfelt letter to his wife. His words reflect the temporary lull in battle and the uncertainty that still loomed over the soldiers. He describes the Regiment’s orders being issued and then suddenly revoked, the quiet yet tense atmosphere along the picket line, and his concerns about missing enlistment papers. Despite the hardships of war, his letter conveys a deep sense of devotion to his family, gratitude for their well-being, and the ever-present possibility of movement or renewed combat. Below is his letter in full:

Camp near Stephensburg

August 9th, 1864

Dear Wife,

I received your letter of the 5th which gave me great pleasure seeing that you and all the family are in good, as this leaves me in at present. Thank God for his mercies to us all. My dear wife, we are laying in camp since the last letter I wrote you. We got orders to move camp this morning. We had all our things packed up, and then the order was countermanded. So, we are in our old camp yet. But we don’t know how long. We thought we would be in Washington before this time. We heard we were going to the defenses of that department. I don’t know whether we will go or not. If we do, I will let you know all about it. Things are very quiet at present, except a few shells fired in the course of the day and night along the picket line. We don’t have any things at present. But I don’t know how long it will last. Let me know if you heard from Bernard yet and how he is. In your next letter, I wish you would send me their enlistment papers that I left in the drawer.

You can fold them up and send them in an envelope to me as I can’t get the description of the men. Without them, the Colonel lost all the rest of my papers and can’t get the description of any of my men for the want of them. The Colonel is here at present. He only came on a visit to see us. He looks first rate. He is going home again tomorrow. Captain Newlin is in command of the Regiment yet. I send you all my love and best respects. Give respects to all my inquiring friends. This is all I have to say at present. So, no more at present. But I remain your affectionate husband,

Eugene Brady[26]

On August 12, the respite came to an end. Brady and the 116th began embarking on steamers at City Point, and the soldiers, believing they were headed to Washington, were filled with excitement and joy. However, their hopes were dashed by midnight when they learned they were heading to Deep Bottom for battle instead of Washington. The mood quickly shifted from one of happiness to one of disappointment. The following day, August 14, they faced extreme heat while marching, digging trenches, and participating in an unsuccessful assault at Fussell’s Mill. That evening, they boarded the steamers again, and despite the earlier suffering, their spirits lifted as they sang songs and felt camaraderie under the stars.

The heat and hardships of the day were remembered as some of the most intense things the soldiers had ever experienced.

On August 15, the Union forces spent the day in picket fighting and trenching, searching for the enemy’s left, but no significant progress was made. On the 16th, the Union cavalry advanced towards Richmond but was forced to retreat after driving the Confederate cavalry back. On August 17, there was heavy skirmishing along the line of the 116th, with casualties on both sides. The armies declared a truce for two hours to remove the dead and wounded. In the afternoon, the Confederates launched an attack, but the Union forces successfully counterattacked, driving them back. Brady and the 116th played a key role in flanking the enemy.

On August 19th and 20th, only light picket firing was done, and the 116th prepared for a withdrawal from Deep Bottom. The march back to Petersburg on the night of the 20th was a miserable experience, marked by heavy rain, thunder, lightning, and treacherous roads, as the picket line was relentlessly exposed to the storm’s fury. After the grueling Deep Bottom campaign, the exhausted troops expected rest but were immediately ordered to work on entrenchments, pushing many to their physical limits. They then endured a forced march in pouring rain to the Gurley House on the Weldon Railroad, collapsing in the mud upon arrival. On August 22nd and 23rd, Lieutenant Brady, with the 116th, helped destroy sections of the Weldon Railroad, bending rails over fires made from railroad ties. Though physically taxing, the soldiers preferred the work over building fortifications under enemy fire. By the evening of the 23rd, they reached Reams Station and took a position in the entrenchments.

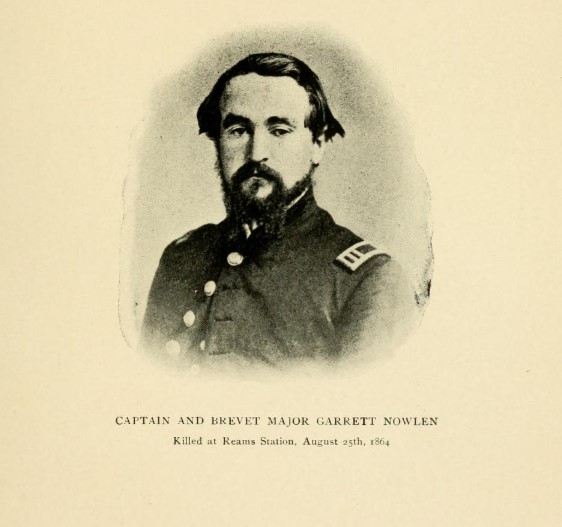

The Battle of Reams Station on August 25, 1864, saw Lieutenant Brady with the 116th defending hastily constructed fortifications against a fierce Confederate assault. Early in the day, Confederate forces advanced, pushing back Union pickets and taking up positions in the surrounding woods. Attempts to reclaim the ground failed, resulting in close-quarters combat and heavy losses. Lieutenant Brady’s letter mentions Captain Garrett Nowlen, whose leadership and bravery left a lasting impression on the men of his Regiment. Nowlen’s heroism was vividly captured during the Battle of Reams Station, where he made the ultimate sacrifice:

“Captain Garrett Nowlen, then in command of the Regiment, stood up in front, waving his sword and cheering on the men. At that moment, a ball pierced his heart. For an instant, he was motionless, then turning quickly to where the men of his own company were in line, he looked towards them and waved his hand: — ‘Good-bye, boys, good-bye — good-bye.’ He was falling when he repeated the last words, and when he struck the ground, he was dead.”[27]

In the afternoon, Confederate forces launched a massive assault, overwhelming parts of the Union line. Brady, with the 116th, fought valiantly. They held their ground until they were forced to retreat under a devastating enfilading fire. As darkness fell, both sides withdrew, marking the battle as a costly defeat for the Union.

After Reams Station, the Regiment spent weeks in reserve, facing constant enemy fire. They moved to the front line in September, enduring two months of relentless trench warfare. The siege of Petersburg saw constant skirmishes between pickets, often escalating into more extensive engagements involving entire brigades and divisions. Nights were especially tense, with gunfire erupting at the slightest sound and sometimes lasting for hours, even when no enemy movement occurred. Soldiers grew accustomed to the noise, sleeping soundly despite the relentless firing. The danger remained ever-present, as numerous lives were claimed each night, with bodies retrieved by dawn and quickly forgotten as life in the trenches carried on.

One cold, quiet night on the picket line outside of Petersburg, Lieutenant Brady entertained his men with a ghost story that revealed his flair for storytelling and the warmth and camaraderie he shared with them. His tale wasn’t of eerie shadows or haunting figures but of a “real Christian ghost.”

“You all remember that on Saturday evening. May 2, at Chancellorsville, the fight was pretty hot for a while, and a good many of our people dropped in the woods on the right of our line. Well, it is of one of them that I will tell you. There was an old lady living at that time in the little village of Hokendauqua, on the Lehigh River, who had a son in the Eleventh Corps. On Sunday morning, May 3, the old lady crossed the river to Catasauqua, a village just opposite to where she lived, and called upon the pastor of a church, with whom she was acquainted. She told him that her son was home and walking around the streets, but he would not speak to her.

‘Last evening (Saturday), ‘ said she, ‘I was washing out some things, the door was open, and who should walk in but my son John. I did not expect him, and I was so astonished for a moment, I did not realize his presence, then quickly drying my hands on my apron, I ran towards him. Would you believe it, he never offered to come towards me but, giving me such a sad, strange look, and without uttering a word, he turned and walked up the stairs. As soon as I could come to my senses, I ran after him, but he was gone. The window was open, and he must have climbed down the trellis-work that the grapevine clings to and so left the house. I lay awake all night thinking and expecting him to come back, but daylight came, and no John. I got the breakfast and started out to hunt him up, and as I was walking along the street, I saw my son just in front of me. I ran to catch up, but he turned a corner, and when I reached there, he was gone. I dare say he went into one of the neighbor’s houses, but which one I could not find out. Now, sir, you can see that my son is evidently angry at something and will not speak to me. Won’t you come over to Hockendaqua to see him, and find out what is the matter ‘? The reverend gentleman, pitying the poor woman, returned with her to her home, hoping to find her boy and have mother and son reconciled. He hunted everywhere through the village but could learn nothing of the soldier. No one had seen him but his mother. On Tuesday morning, May 5, a letter came saying that the boy had been killed on Saturday evening, just at the time that he walked in to see his mother. Gentlemen, that is a true story of a Christian soldier in full uniform and in broad daylight, and no sad-eyed Hindoo prowling around at midnight, dressed in white,”[28]

Lieutenant Brady’s devotion to his men went beyond morale-boosting stories and camaraderie; it was a commitment that extended to the battlefield itself. During a tense moment in the siege of Petersburg, he proved this again when he spotted young William J. Curley, the drummer boy of Company E, wandering dangerously into the open, unaware that he was in the enemy’s sights as he searched for his company.

“Lieutenant Brady, of Company D, seeing his danger, called to him to jump into one of the rifle pits. Before he had time to do so, however, a Johnny let go and sent a ball through the head of Curley’s drum.”[29]

Shortly after this harrowing incident, the Army granted Lieutenant Brady leave to return home and care for his pregnant wife, Mary. His departure was a brief respite from the relentless dangers of the front lines, allowing him a moment of solace with his family before duty called him back to the Regiment. Mary gave birth to their fourth child, Cecilia, on December 12, 1864.[30] Before returning to the front, Lieutenant Brady seemed to have a premonition of his fate. Upon the expiration of his short furlough, just a few months before his death, he bid his friends goodbye with solemn certainty, telling them that he would not see them again.

In late March 1865, the war’s final campaign began with relentless marching and combat. On March 28, Lieutenant Brady and the 116th withdrew from Petersburg and advanced leftward, crossing Hatcher’s Run. Fighting erupted near Dabney’s Mill despite torrential rain that flooded the terrain. By March 30, Lieutenant Brady and the Regiment faced continuous fire from all sides, leaving no time for rest, food, or sleep. Even attempts to make coffee were thwarted by enemy fire. The Regiment suffered significant losses before linking up with additional Union forces as the intense battle continued.

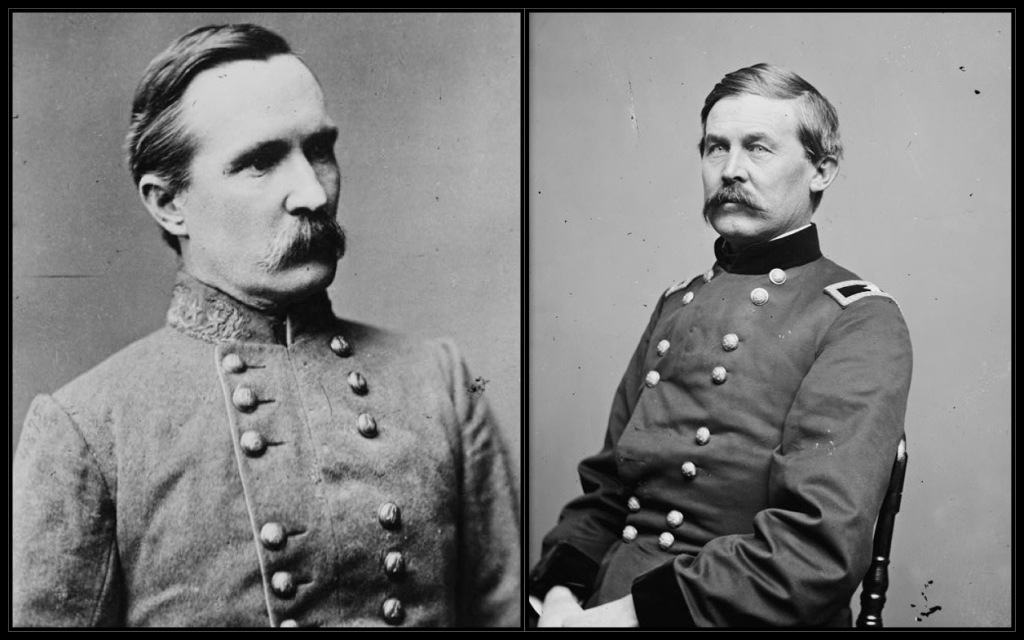

The battles on March 31 and April 1 were brutal, with the 116th Regiment fighting valiantly but suffering devastating losses. On March 31st, during a skirmish near Five Forks, Lieutenant Eugene Brady, a courageous and respected officer, lost his life. The Regiment’s casualties were heavy, and many of the dead remained where they fell, making the full extent of the losses unknown. During the battle, General Lee personally led the Confederate forces, launching a fierce attack that initially broke the Union line. However, the Union, with the help of the 116th, counterattacked with remarkable force, driving back the Confederate brigades, capturing prisoners and a flag, and restoring the Union lines.

Lieutenant Eugene Brady met his end in an act of fearless leadership that day while leading a small group of men in a daring assault on an enemy rifle pit. Brady’s courage and sacrifice in that moment embodied the unwavering resolve of the Regiment in the war’s final, brutal days.

Sergeant Edward S. Kline later recounted the harrowing experience, saying,

“I remember distinctly, after wading across a creek, that the enemy had some rifle pits on a hill in a field, and Lieutenant Brady said, ‘Let us go for that pit.

‘Together with four or five other men, I joined him, and we succeeded in gaining possession of the pit, but the enemy soon had a flank fire on us. I think I was the only survivor. Lieutenant Brady was killed first. He made some remark about a Confederate color-bearer shaking his flag at us from behind a tree some hundred yards distant when he was hit right in the forehead. He fell against me and died instantly.”[31]

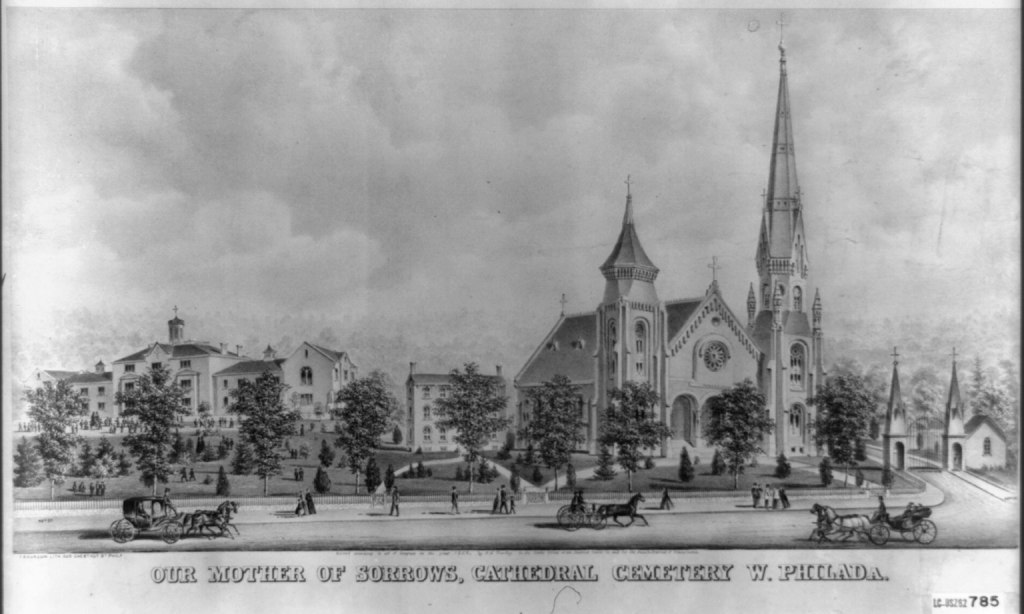

With the rest of the men likely lost, Kline barely escaped, carrying Brady’s shoulder straps and memorandum book to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. Later, when the Union forces pushed forward, Kline returned with a detail to recover Brady’s body, ensuring he was placed in the care of the regimental surgeon, Dr. Wm. B. Hartman. Lieutenant Brady’s remains were transported to Philadelphia, where he was laid to rest in Old Cathedral Cemetery.

After Lieutenant Brady’s tragic death, his wife, Mary, was left to navigate an uncertain future, raising their four children without her husband’s support. On April 24, 1865[32], she applied for a widow’s pension, which she eventually received at a rate of $17 per month, equivalent to approximately $331 today[33]. Mary worked as a domestic servant to make ends meet, persevering through hardship to provide for her family. Mary lived until 1913, passing away from nephritis.[34]. Mary’s son later sought government assistance to cover her funeral expenses, which totaled $307, but the request was denied, as her estate was deemed sufficient to bear the cost.

As we remember First Lieutenant Eugene Brady, we see more than just a name in history; we glimpse a life marked by courage, devotion, and sacrifice. From his humble beginnings on the Emerald Isle to the brutal battlefields of the Civil War, Brady’s story echoes the resilience of countless immigrants who risked everything for a cause greater than themselves. Brady’s unwavering courage and sacrifice, as well as his loyalty to his men and his family, even in the face of certain death, speak volumes about the strength of the human spirit. Let us honor his memory and the sacrifices of all soldiers by working toward a future where peace triumphs over war.

[1] “Eugene Brady in the 1860 United States Federal Census.” Ancestry, 2009. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7667/records/4518410?tid=&pid=&queryId=44e3a92f-caee-4119-9ad5-0198226eea4c&_phsrc=JHJ1157&_phstart=successSource.

[2] “Page 5 – US, Civil War ‘Widows’ Pensions’, 1861-1910.” Fold3, 2008. https://www.fold3.com/image/271287394/brady-eugene-page-5-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910.

[3] “Pennsylvania, U.S., Civil War Muster Rolls, 1860-1869.” Ancestry®, 2015. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/9040/records/19699?tid=&pid=&queryId=2ba0a779-d445-4b3d-8fd4-b83751451d16&_phsrc=JHJ1175&_phstart=successSource.

[4] Ibid

[5] Mulholland, St. Clair A. The Story of the 116th Regiment: Pennsylvania Volunteers in the War of Rebellion: The Record of a Gallant Command. 1st ed. Philadelphia, United States of America: F. McManus, Jr. & Co., 1903. Pg’s 35-36

[6] Ibid Pg’s 43-44

[7] Ibid. Pg. 47

[8] “230 Series I Volume XXI- Serial 31 – Fredericksburg,” n.d., https://www.civilwar.com/battles/927-official-record/series/volume/campaign/fredericksburg/177626-230-series-i-volume-xxi-serial-31-fredericksburg.html.

[9] “Page 1 – US, Pennsylvania Veterans Card Files, 1775-1916,” Fold3, n.d., https://www.fold3.com/image/712041844/brady-eugene-page-1-us-pennsylvania-veterans-card-files-1775-1916.

[10] Mulholland, St. Clair A. The Story of the 116th Regiment: Pennsylvania Volunteers in the War of Rebellion: The Record of a Gallant Command. 1st ed. Philadelphia, United States of America: F. McManus, Jr. & Co., 1903. Pg. 93

[11] Ibid, Pg’s 96-97

[12] Ibid Pg. 99

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid Pg. 100

[15] Ibid Pg’s 100-101

[16] Ibid 101

[17] Ibid. Pg. 372

[18] Ibid. Pg. 125

[19] “Civil War Data,” n.d. https://www.civilwardata.com/personnel/usa/925912.

[20]Ibid, Pg. 186

[21] Ibid, Pg’s 189-190

[22] Ibid Pg. 210

[23] Ibid Pg. 255

[24] Ibid Pg. 256

[25] Ibid Pg. 269

[26] Brady, Eugene. Letter to Mary Brady. August 9, 1864. Camp Near Stephensburg. In possession of The American Military Heritage Museum Of North Carolina

[27] Mulholland, St. Clair A. The Story of the 116th Regiment: Pennsylvania Volunteers in the War of Rebellion: The Record of a Gallant Command. 1st ed. Philadelphia, United States of America: F. McManus, Jr. & Co., 1903. Pg. 294

[28] Ibid Pg. 314-16

[29] Ibid Pg. 318

[30] Fold3. “Page 2 – “US, Civil War Pensions, 1861-1910,” n.d. https://www.fold3.com/image/271287391/brady-eugene-page-2-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910.

[31] Mulholland, St. Clair A. The Story of the 116th Regiment: Pennsylvania Volunteers in the War of Rebellion: The Record of a Gallant Command. 1st ed. Philadelphia, United States of America: F. McManus, Jr. & Co., 1903. Pg. 337

[32] Fold3. “Brady, Eugene – Fold3 – US, Civil War &Quot;Widows’ Pensions&Quot;, 1861-1910,” n.d. https://www.fold3.com/file/271287390.

[33] “Inflation Rate Between 1865-2025 | Inflation Calculator,” n.d. https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1865?amount=17.

[34] “Mary C Brady in the Pennsylvania, U.S., Death Certificates, 1906-1971