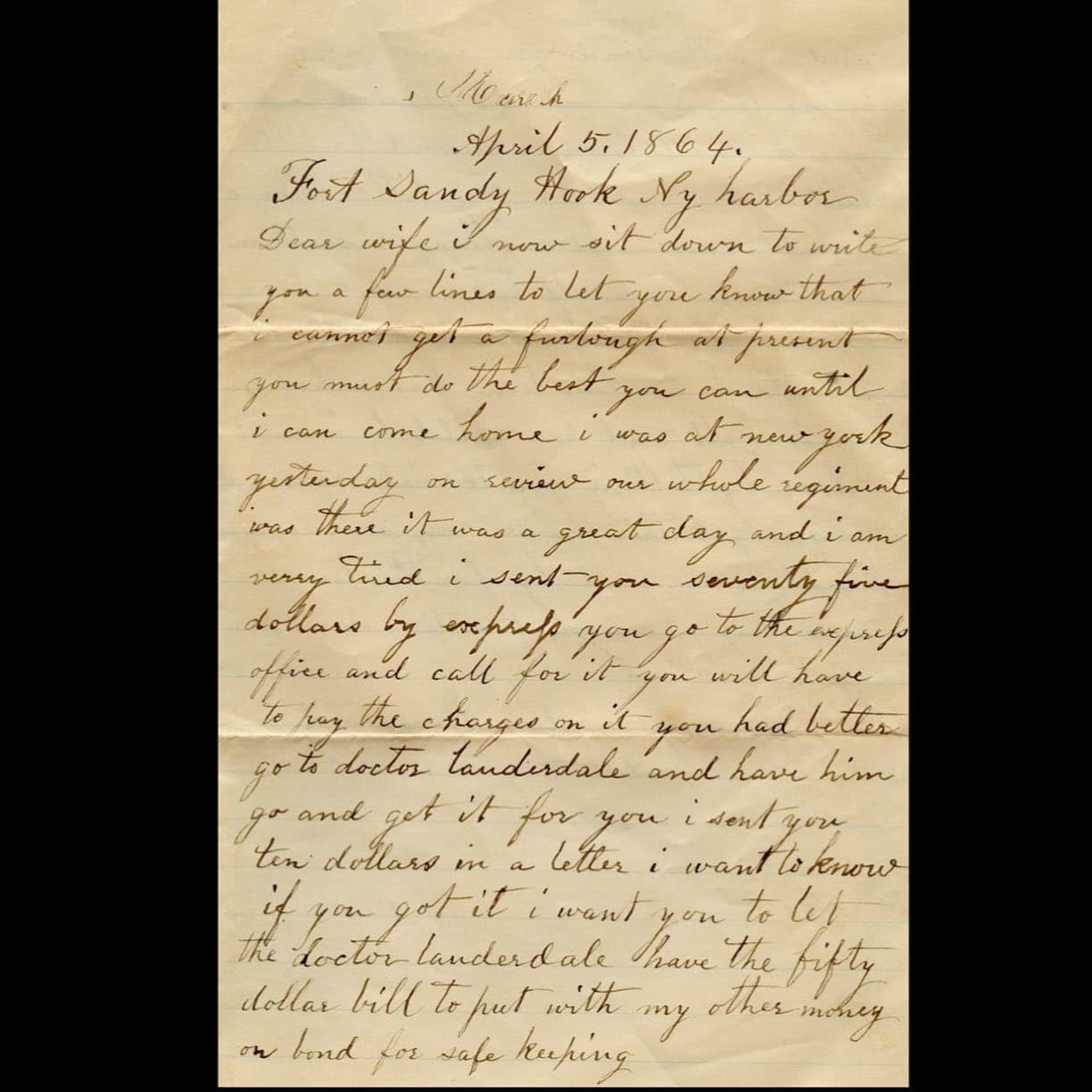

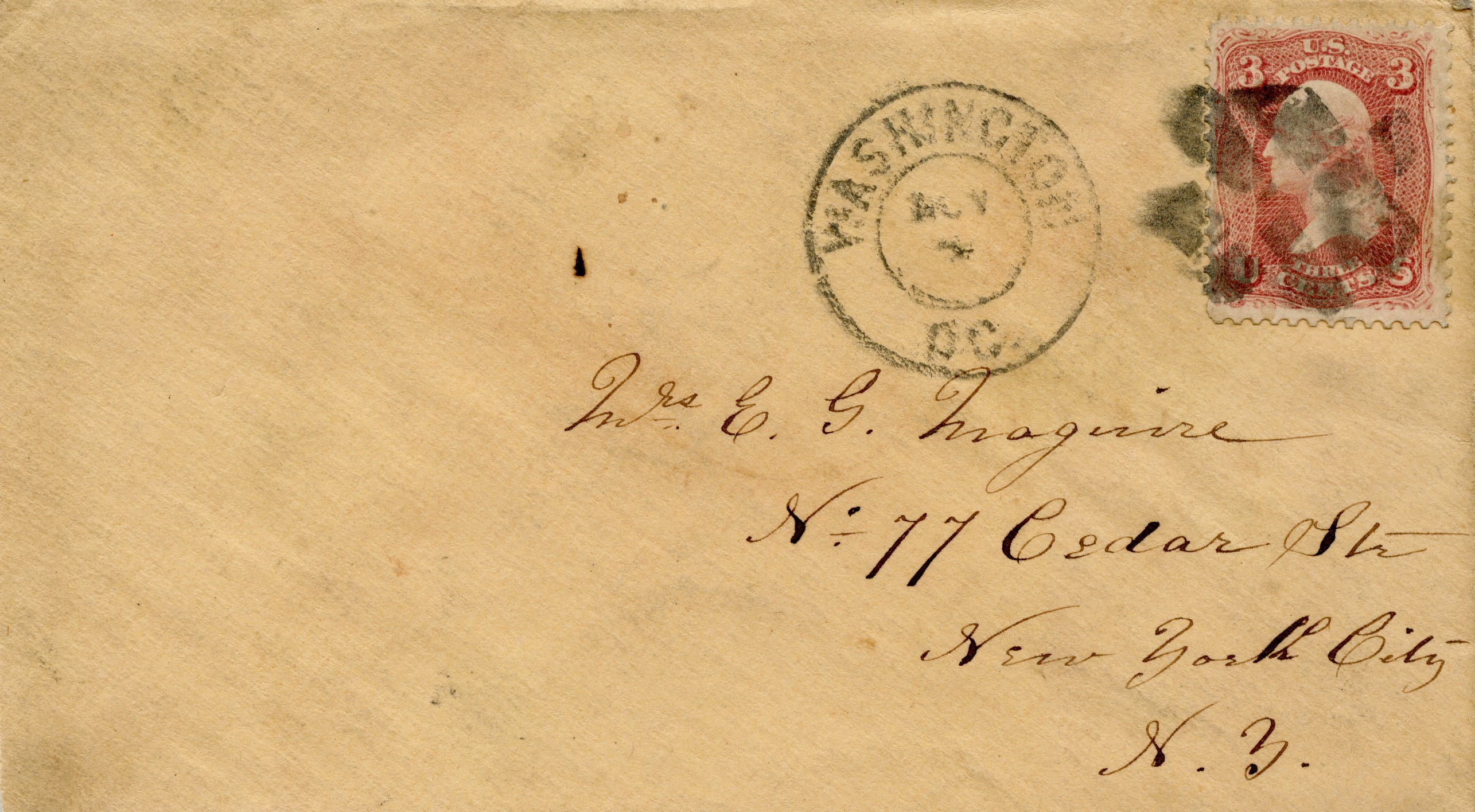

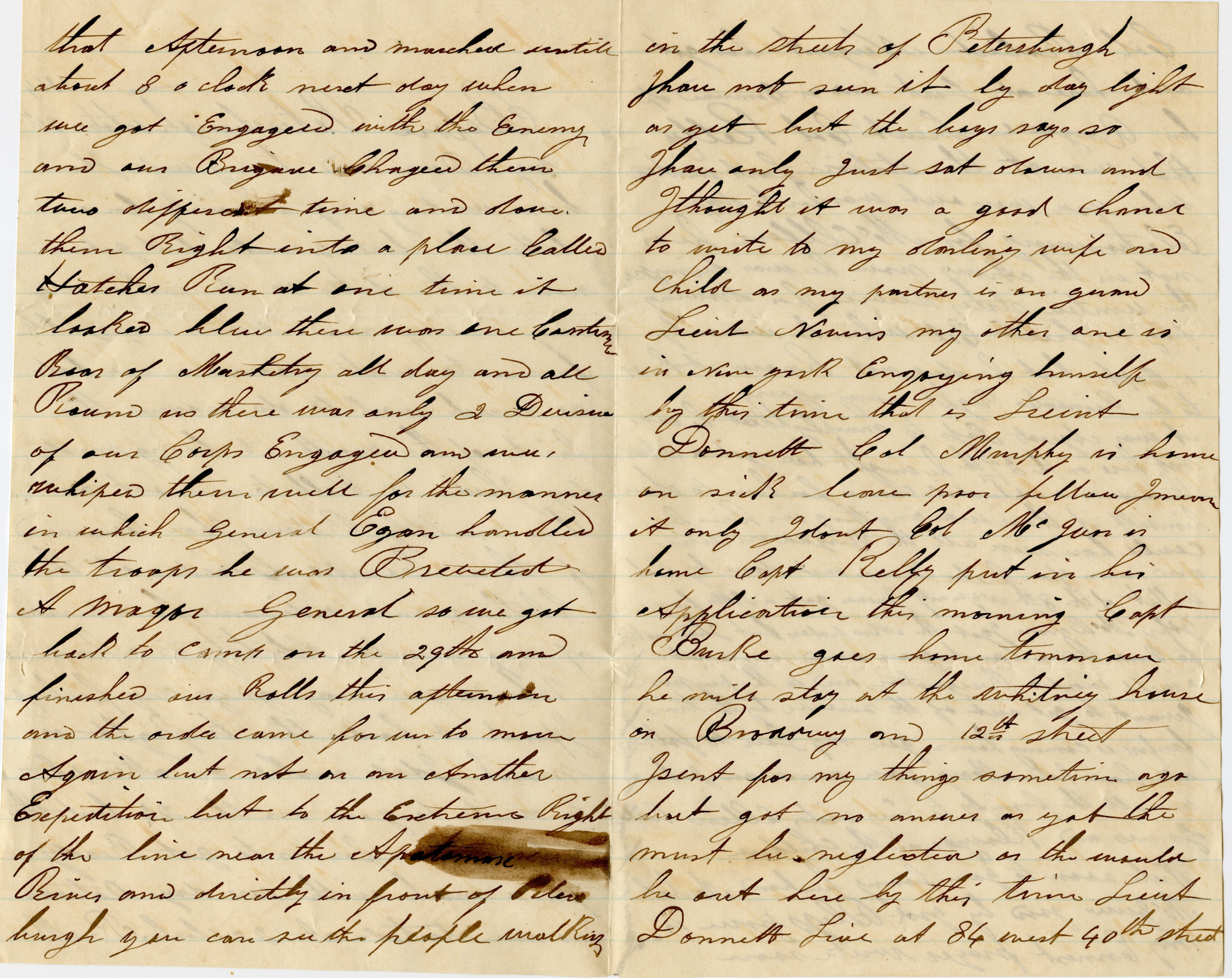

It never ceases to amaze me, how a letter can come alive with some digging. This letter written by then Captain Michael McGuire to his wife Elizabeth is one such correspondence. The document is dated October 31st, 1864. It reads…….

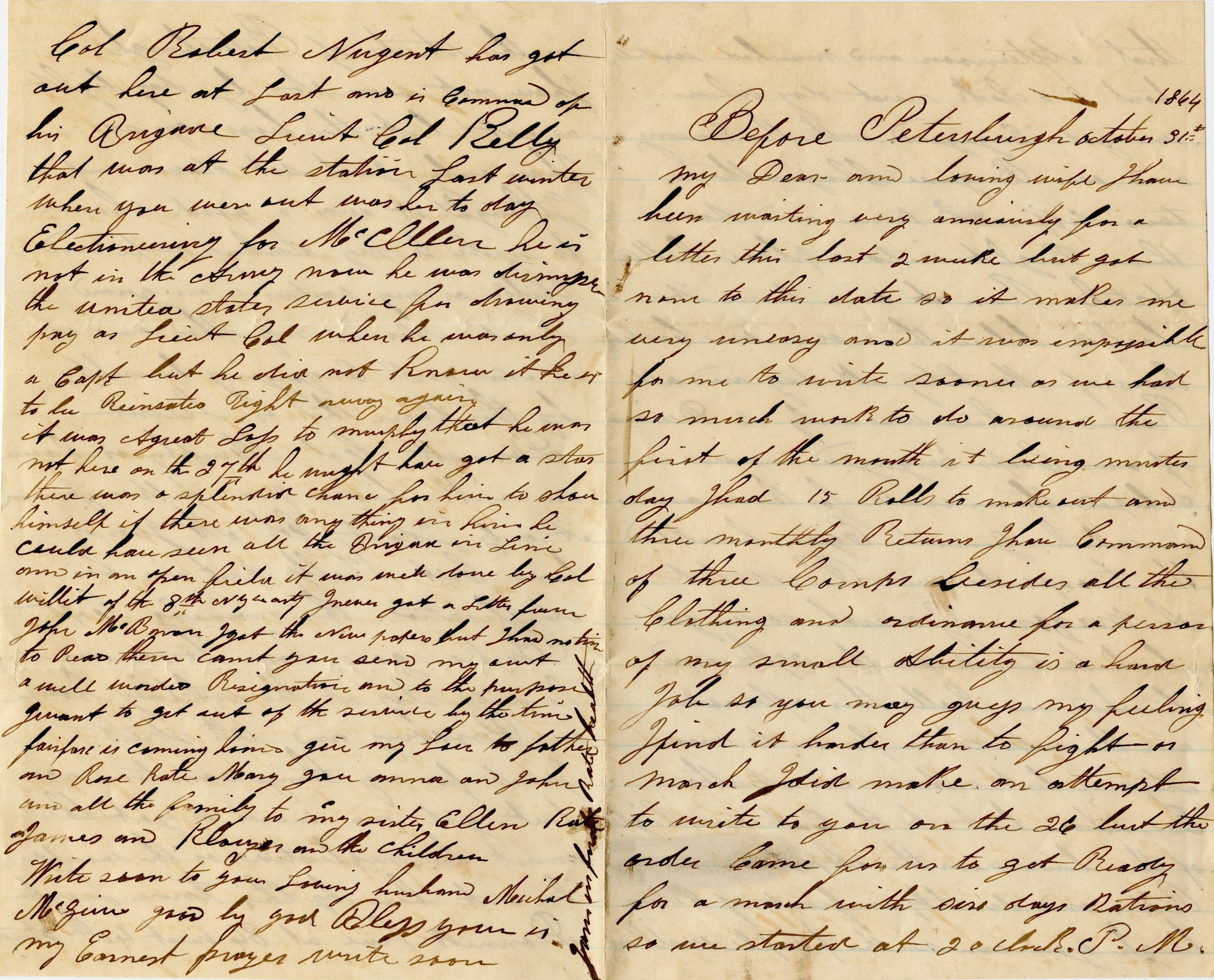

“Before Petersburg

October 31st, 1864,

My Dear and Loving Wife, I have been waiting very anxiously for a letter this last 2 weeks but got none to this date. So it makes me very uneasy and it was impossible for me to write sooner as we had so much work to do around the first of the month, it being muster day. I had 15 rolls to make out and three- monthly returns. I have command of three camps besides all the clothing and ordnance. For a person of my small ability is a hard job. So you may guess my feeling.

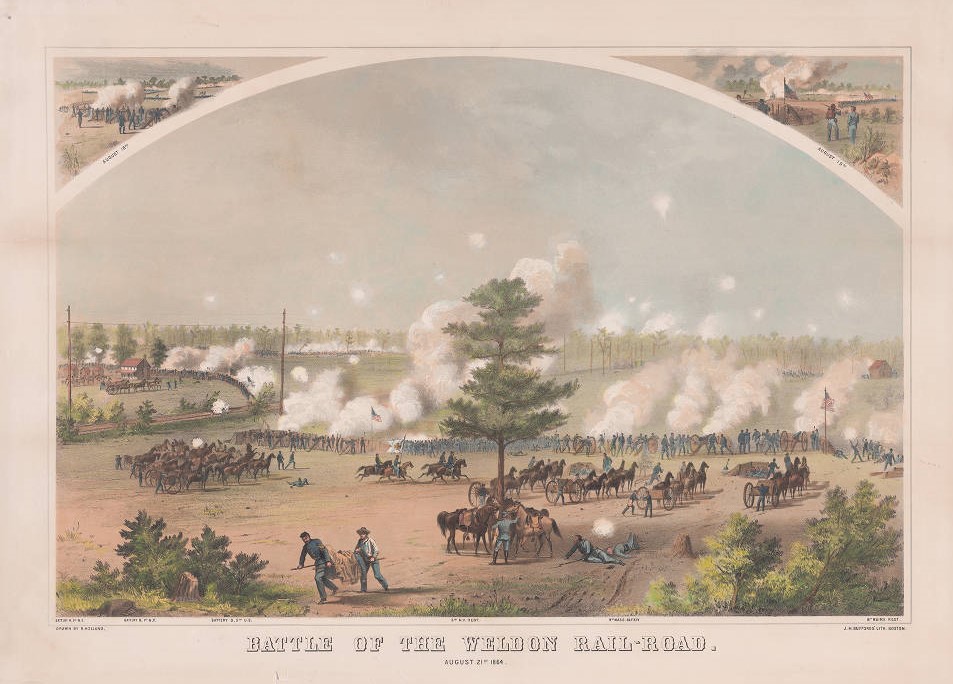

I find it harder than to fight or march. I did make an attempt to write to you on the 26th, But the order came for us to get ready for a march with six days rations. So, we started at 2 o’clock p.m. that afternoon and marched until about 8 o’clock next day when we got engaged with the enemy and our charged them two different times and them right into a place called Hatcher’s Run. At one time it looked like there was one canteen, roar of musketry all day and all might as there was only two divisions of our corps engaged and we whipped them well for the manner in which General Egan handles the troops. He was breveted a Major General.

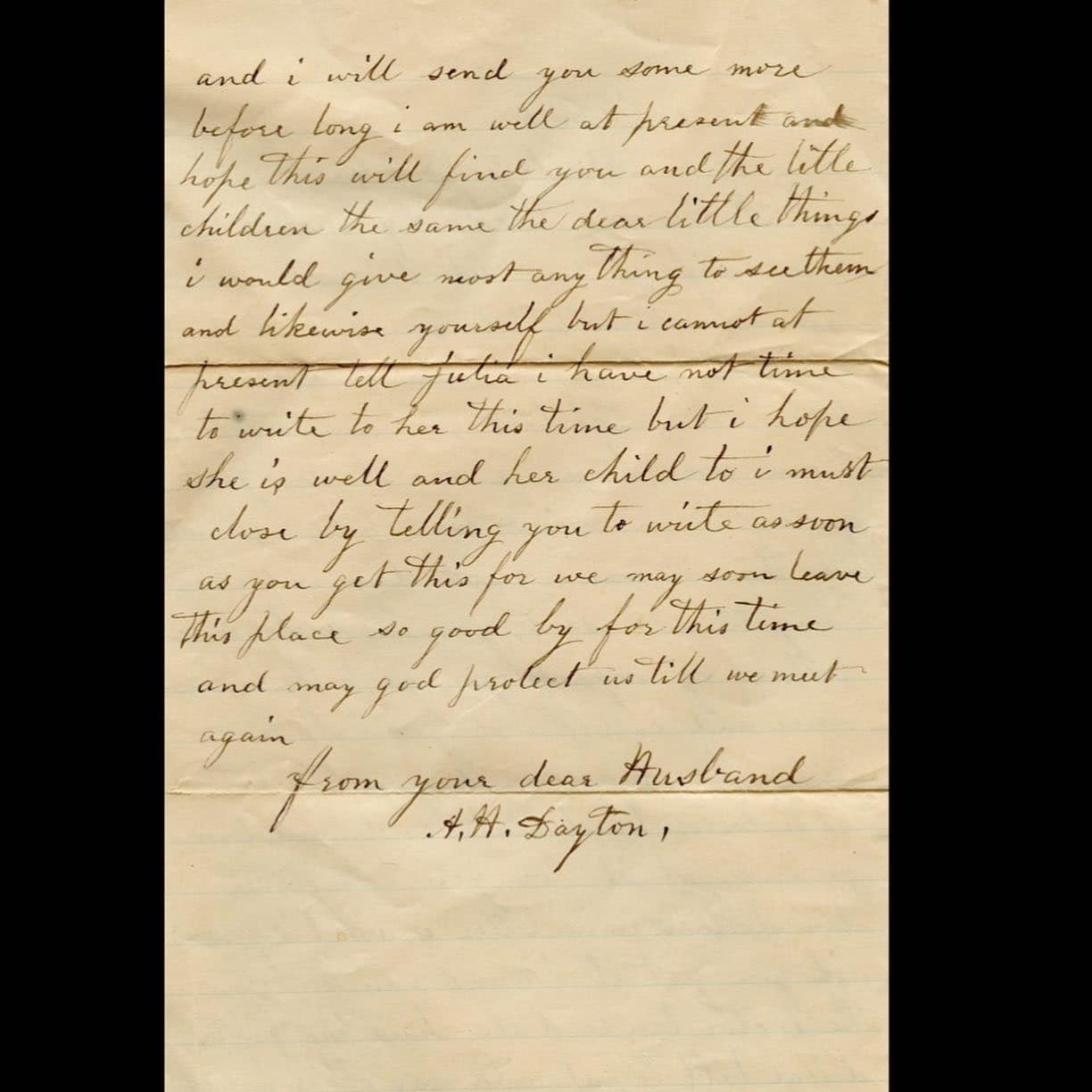

So, we got back to camp on the 29th and finished our rolls this afternoon. And the order came for us to move again. But not on another expedition. But to the extreme right of the line near the Appomattox River and directly in front of Petersburg. You can see the people walking in the streets of Petersburg. I have not seen it by daylight as yet. But the boys say so. I have only just sat down and I thought it was a good chance to write to my darling wife and child. As my partner is on guard., Lieutenant Nevin. My other one, is in New York enjoying himself by this time. That is Lieutenant Donett. Colonel Murphy is home on sick leave. Poor fellow. I mean it, only I don’t. Colonel McGunn is home. Captain Kelly put in his application this morning. Captain Burke goes home tomorrow. He will stay at the Whitney House on Broadway and 12th Street. I sent for my things sometime ago. But got no answer as yet. They must be neglecting or they would be out here by this time.

Lieutenant Donett lives at 86 West 40th Street. Colonel Robert Nugent has got out here at last and in command of his Brigade. Lieutenant Colonel Kelly that was at the station last winter when you were out, was here today electioneering for McClellan. He is not in the army now. He was dismissed from the United States service for drawing pay as lieutenant colonel when he was only a captain. But he did not know it. He is to be reinstated right away again. It was a great loss to Murphy that he was not here on the 27. He might have got a star.There was a splendid chance for him to show himself if there was anything in the fight. He could have seen all the Brigade in line and in an open field. It was not done by Colonel Willett of the 8th New York Artillery.

I never got a letter from John McBowen. I got the newspapers but I had no time to read them.

Can’t you send me out a well worded resignation and to the purpose I want to get out of the service by the time Fairfax is coming soon.

Give my love to Father and Rose Kate, Mary, you, Anna and John and all the family. To my sister Ellen, Kate and James and Klayer and the children.

Write soon to your loving husband,

Michael McGuire,

Goodbye. God Bless You. It is my earnest prayer. Write soon.

James is in first rate health.”

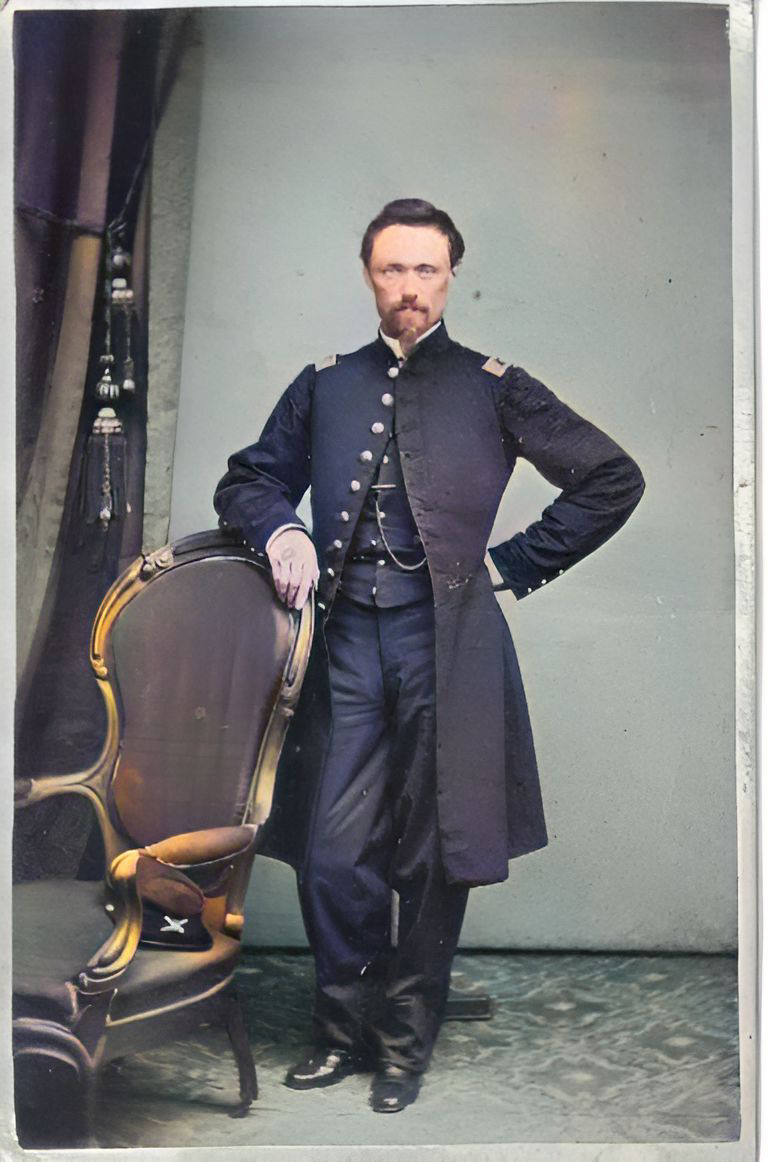

Colorized by @Pixelup

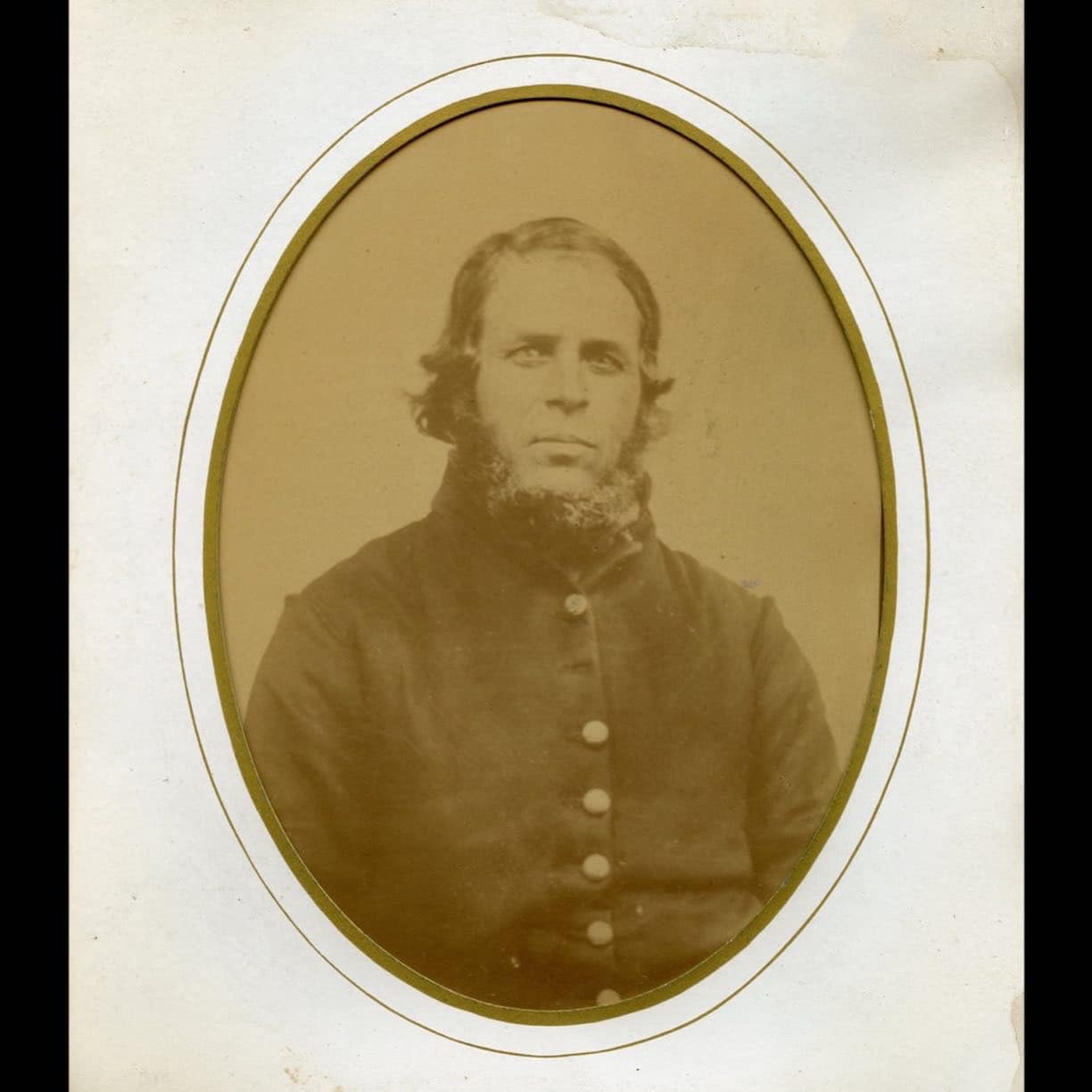

McGuire was born in Caltra, County Galway Ireland on September 3rd, 1833. [1]The famine would force him to emigrate from Ireland abord the Clipper “Fidelia”, on October 6th, 1847.[2] He was described as five feet seven inches tall with blue eyes, brown hair, and a light complexion.[3] McGuire would settle into New York City and become a naturalized citizen in 1856.[4] Before the outbreak of the American Civil War McGuire would marry Elizabeth Moore. They would have a son in February of 1861.[5]

McGuire would enlist on April 20th, 1861,[6] and be mustered into company “D” 69th New York State Militia as a private. He would be with the regiment during First Bull Run where he was wounded. McGuire would be promoted to Captain of the 69th and later enlist in the 182nd New York. He would be commissioned a Capt. of that regiment on November 17th, 1862.[7]

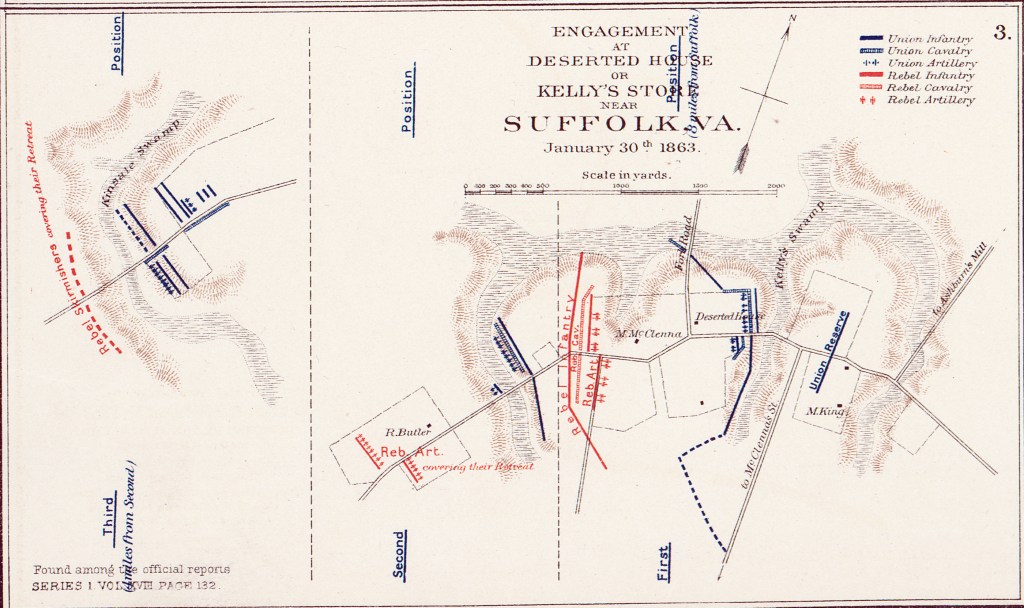

Captain McGuire participated in the following engagements, The Battle of Deserted House, The Siege of Suffolk, Spotsylvania Court House, North Anna River (wounded left forearm), and Hatchers Run (wounded right side of chest). He would be promoted to Brevet Major on July 15th, 1865.[8]

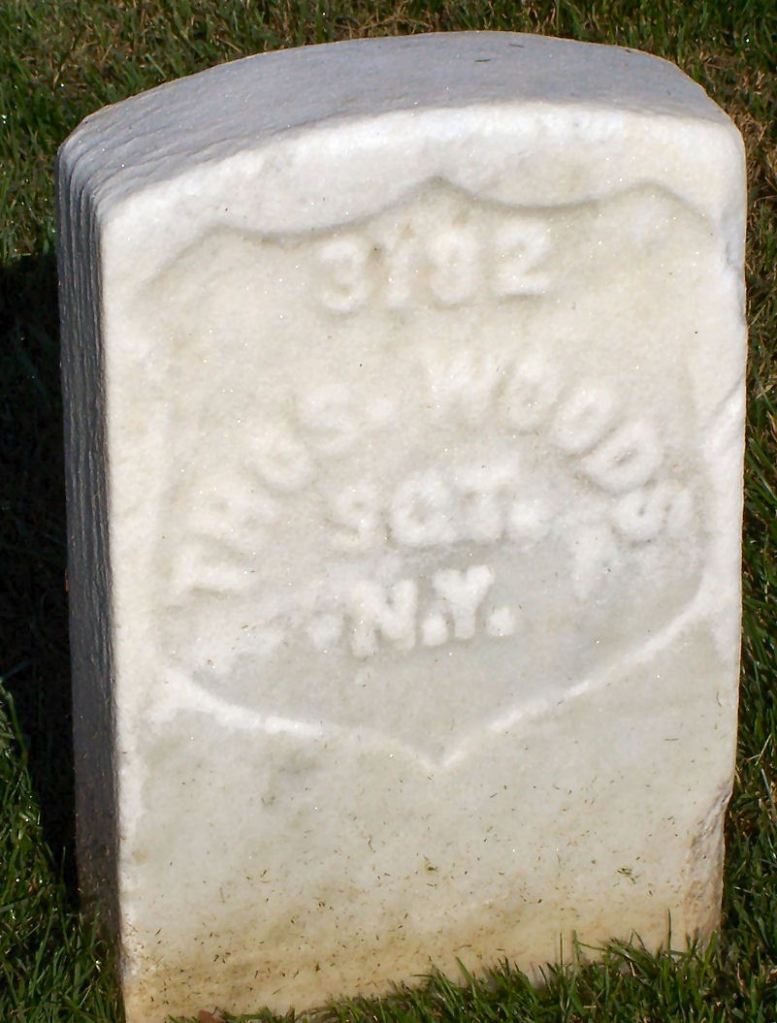

After the war McGuire was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel of the 69th N.G.S.N.Y. Sadly, his wife Elizabeth would die of consumption on September 18th, 1869,[9]. He and his son would own a successful contracting company in Brooklyn. McGuire would marry Eliza T. Cloonan in 1873[10] and they would have one son. Lieutenant Colonel McGuire would die of Pneumonia in 1909.[11] The local chapter of the Grand Army of The Republic, provided full military honors at his burial. McGuire now rests in New York’s’ Calvary Cemetery.

[1] Maguire47. (n.d.). Dad’s Great G Pops, Lt. Col Michael Maguire GAR Obit 10-1-09. Ancestry.Com. Retrieved from https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/5960414/person/-1368421212/media/ba18d35a-8540-4f73-b53b-f807e410c755

[2] “New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Immigration Lists, 1820-1850.” Ancestry. Accessed July 28, 2023. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/839884:7485?ssrc=pt&tid=30840402&pid=12456814137.

[3] Maghe, Joseph. Captain Michael McGuire. May 2, 2016. Https://Tinyurl.Com/3nruc2m3.

[4] McGuire, Nadine Freeman. “Naturalization.” Ancestry, n.d. https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/30840402/person/12456814137/facts?_phsrc=csG378&_phstart=successSource.

[5] McGuire, Nadine Freeman. “Birth of Son” Ancestry, n.d. https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/30840402/person/12456814137/facts?_phsrc=csG378&_phstart=successSource.

[6] Maghe, Joseph. Captain Michael McGuire. May 2, 2016. Https://Tinyurl.Com/3nruc2m3.

[7] “Michael McGuire New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts.” Fold3. Accessed July 29, 2023. https://www.fold3.com/image/316249792?terms=war%2Cyork%2Cus%2Ccivil%2Cnew%2Cunited%2Camerica%2Cmcguire%2Cmichael%2Cstates.

[8] Maghe, Joseph. Captain Michael McGuire. May 2, 2016. Https://Tinyurl.Com/3nruc2m3.

[9] Ibid

[10] McGuire, Nadine Freeman. “Marriage 1872” Ancestry, n.d. https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/30840402/person/12456814137/facts?_phsrc=csG378&_phstart=successSource.

[11] McGuire, Nadine Freeman. “Death” Ancestry, n.d. https://www.ancestry.com/family-tree/person/tree/30840402/person/12456814137/facts?_phsrc=csG378&_phstart=successSource