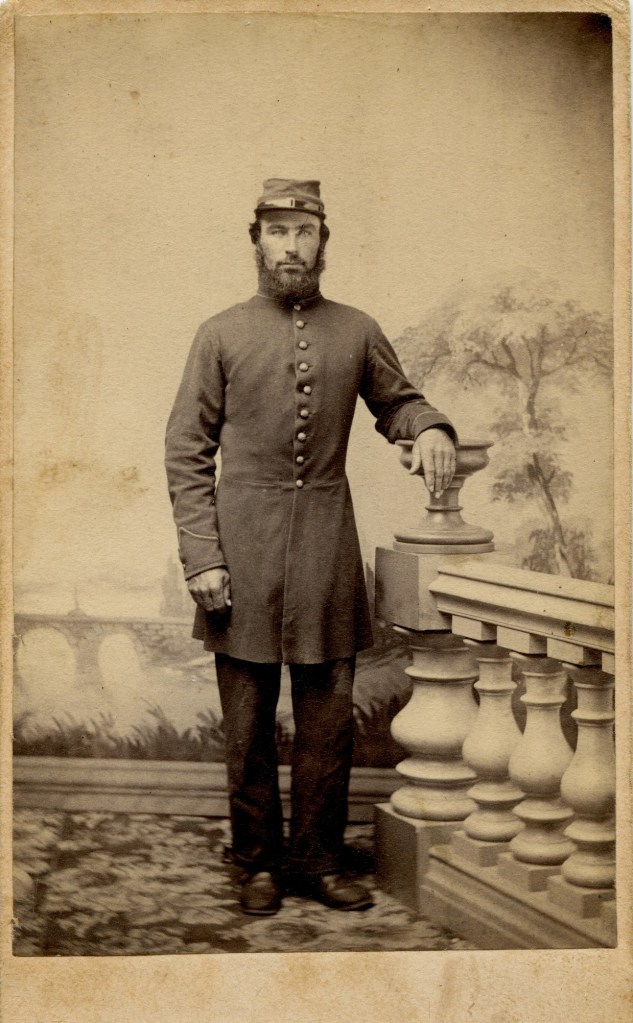

The American Civil War was a pivotal moment in the history of the United States. It marked a turning point in the country’s path toward becoming a united and free nation. However, along with the bravery and sacrifices of soldiers on both sides, there were also instances of tragedy and loss. One such heartbreaking story is that of James Hews, a member of the 118th New York Infantry. His story is not just one of a soldier’s bravery and courage but also one of a preventable tragedy. He was ultimately killed not by the enemy but by his own men. This is the story of James Hews, a soldier whose life was cut short by the very hands of his brothers in arms.

James Hews was born in England on August 4th, 1834. [1] He was the second of four children born to William and Elizabeth Hews. The family immigrated to America around 1840[2]. They would eventually settle in Chester, New York. Here, they would establish a small farm. James would meet and court Sarah Jenks. They would marry on January 1st, 1857. [3]

During the initial months of 1860, the forthcoming presidential election, with its unsettling implications, captivated people’s attention. The election of Abraham Lincoln had a significant impact on the American Civil War. His victory as President of the United States played a crucial role in deepening the divide between the northern and southern states. Lincoln’s anti-slavery beliefs made the southern states feel threatened, and they saw his election as a direct threat to their way of life. This fear ultimately led to their secession from the Union. By triggering the secession of the southern states, Lincoln’s election set the stage for the bloody conflict that followed, as the Union fought to preserve the nation’s unity and end slavery.

The first two years of the Civil War were not the most successful for the Union army. Although there were a few bright spots in the conflict, the overall picture was bleak.

“In the midst of this depressing gloom came the startling but heartening call of our President for 300.000 men for three years! It was an awakening call and aroused the patriotism of the people. The pessimists, and they were plenty, believed that with so much serious demonstration of what enlistment meant the call could not be met by volunteers. They underestimated the patriotic spirit of the people. Out of these conditions and under these circumstances came the “Adirondack Regiment” “ [4]

It was under these circumstances that James Hews enlisted on July 28th, 1862. [5] At the time of his enlistment, Hews was listed as being five feet eight inches tall, with blue eyes, brown hair, and a light complexion. He would be mustered into “D” Company of the 118th New York Infantry on August 8th, 1862[6] as a private.

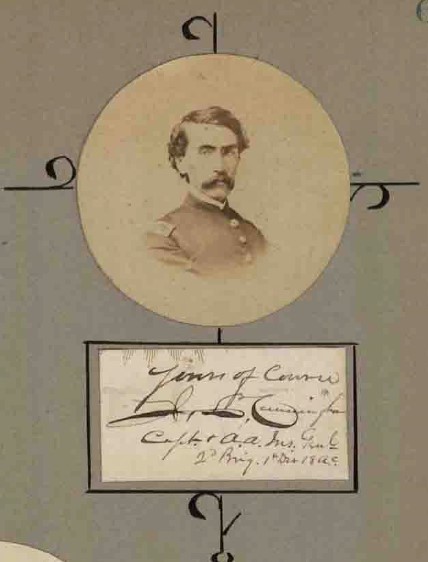

Marching orders were given to the 118th on the evening of September 1st.[7] Private Hews and his regiment marched through a drizzle to catch a steamship to Whitehall, NY. In his book, Three Years with the Adirondack Regiment, Major John L. Cunningham sets the scene by saying…

“The streets were lined with men, women, and children shouting their goodbyes with occasional audible sobs as near and dear ones passed by… it was more solemn than hilarious to marchers and lookers-on.” [8]

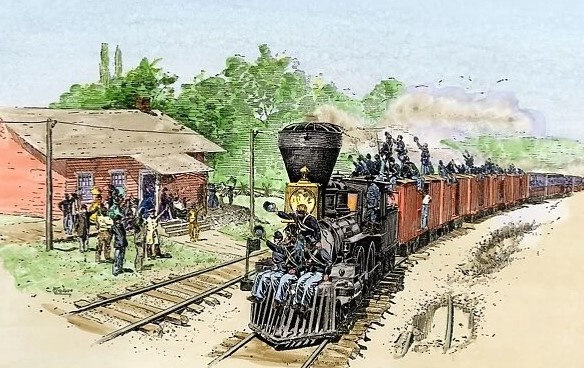

Once in Whitehall, they were crammed into the boxcars of a freight train bound for Albany. The regiment would reach Albany around noon on the second[9]. Here they had lunch and were loaded onto cattle cars with “evidence of their late occupancy”[10]. This putrid and soiled train was bound for New York City.

Courtesy of http://hardtackregiment.com/links.html.

Once, In New York City, Pvt. Hews and the 118th marched to City Hall Park. Here they were billeted on the grounds. A tall iron fence encircled the park, which had a flatiron-shaped design. Makeshift barracks were erected in the upper area of the park containing bunk beds. This is where they would bed down for the night. The noise of the city would awaken Pvt. Hews and the regiment. They crowded against the fence and interacted with merchants and the people of the city. Major Cunningham establishes the setting with his statement.

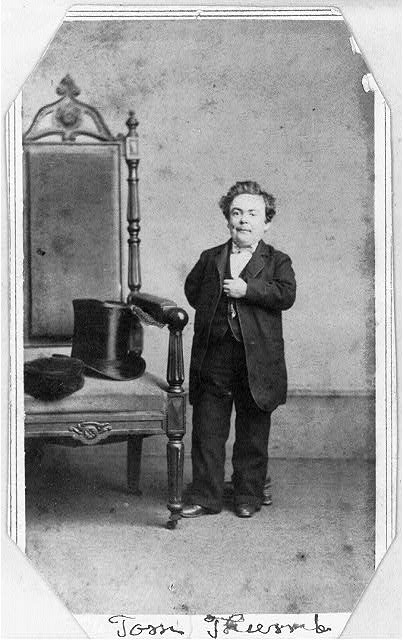

“About half past one of that afternoon, the band of Barnum’s Museum appeared on the balcony of that notable showplace, just across the street from us. We country-fellows knew much of Barnum’s Museum by reputation and yearned to see its inside for ourselves. Tom Thumb was one of the then leading features of that show and his diminutive coach and ponies, out for advertising, came down the sidewalk on the east side of our enclosure and our men massed themselves against the iron fence to get a glimpse of the coach and followed it in pell-mell fashion as it proceeded towards the narrow point of the park. The men reached the gates in a mass and overran the guard, those in front being forced through the gate by the pressing crowd behind. Before our reserve guard could be used, a blue streak of men headed for the museum, to the holding up of the large traffic of that vicinity.”[11]

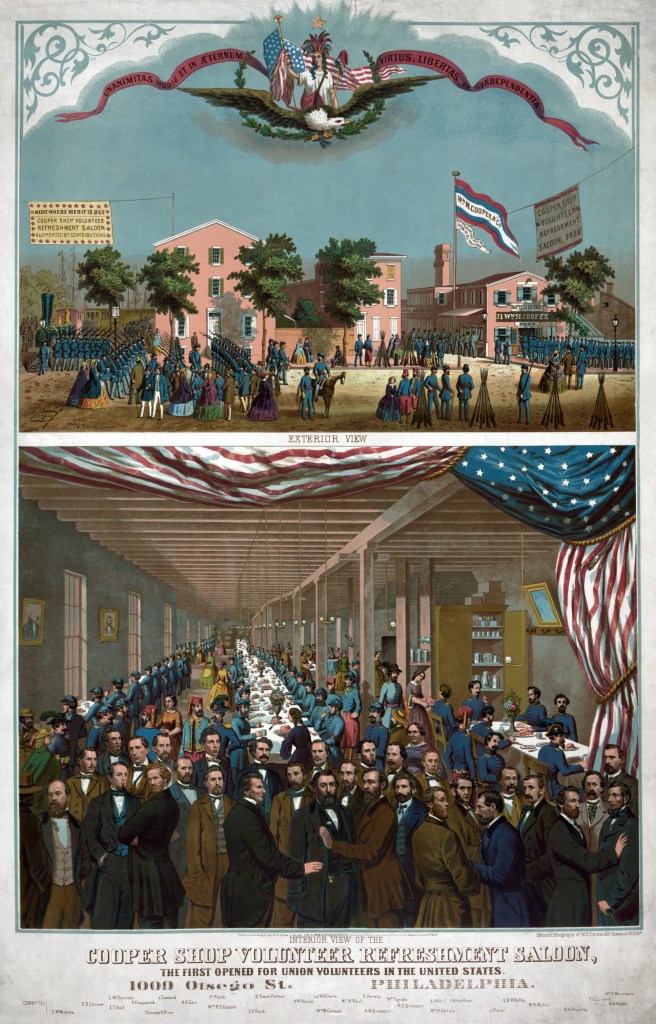

At around five o’clock that evening, assembly was called. By then, most of the men had returned from their adventure. Pvt. Hews and the 118th assembled, and marched down Broadway to a steamer, “’mid a shouting side-walk multitude.” [12] They took the ship to Philadelphia and made it just in time for breakfast at the “Cooper Shop.” After a hardy breakfast, they marched a large distance to the train station. Here, Pvt. Hews and the 118th would catch a train to Baltimore. They would reach Baltimore later that evening. At that time, Baltimore was a tinder box, as both Unionists and Southern sympathizers occupied the city. Pvt. Hews and the 118th, having not yet been issued arms, were in quite a predicament.

Photograph Courtesy of https://www.loc.gov/item/2021670373/.

They had to march a long route through downtown to reach the Ohio Station. This scene is expertly described by Major Cunningham…

“We were ordered to make no utterances and pay no attention to the utterances of others. We heard distinct hisses from behind many a window shutter and reaching the business section found crowds of excited people indulging in all sorts of shouts of derision and threats, mingled with occasional friendly salutations.” [13]

Major Cunningham continues to say they heard “all sorts of angry, vituperative shouts. “The more Northern scum the more fertilizer for Southern cotton fields “: “Better stop here and surrender to Lee, he’ll be here in a few days,” etc., etc. The excitement was threatening, and it seemed as if we might be attacked, but we reached the station unmolested.”[14]

The next morning, they would receive their arms and orders to guard the junction of the Washington and Harper’s Ferry trains. Given its status as the sole railway connecting Washington from the north, it was crucial to protect and secure it from potential acts of sabotage.

The 118th spent most of its time here engaged in daily exercises. The deployment was punctuated by a few false alarms of southern incursions, including one that resulted in the accidental shooting death of a train engineer. Major Cunningham describes the tragic accident by writing…

“Our men were scattered along the road in “bunches” of four or more, the groups being within sight of each other, one man to be on watch all the while, and when a train approached, he called out all the group, they to stand at present arms till the train passed. On the coming of this train the guard was called out and in hurrying into position the gun of one man, Eugene Dupuis of our company, was accidentally discharged. The bullet struck the smokestack of the engine, glanced, and hit the engineer in his forehead, killing him instantly.”[15]

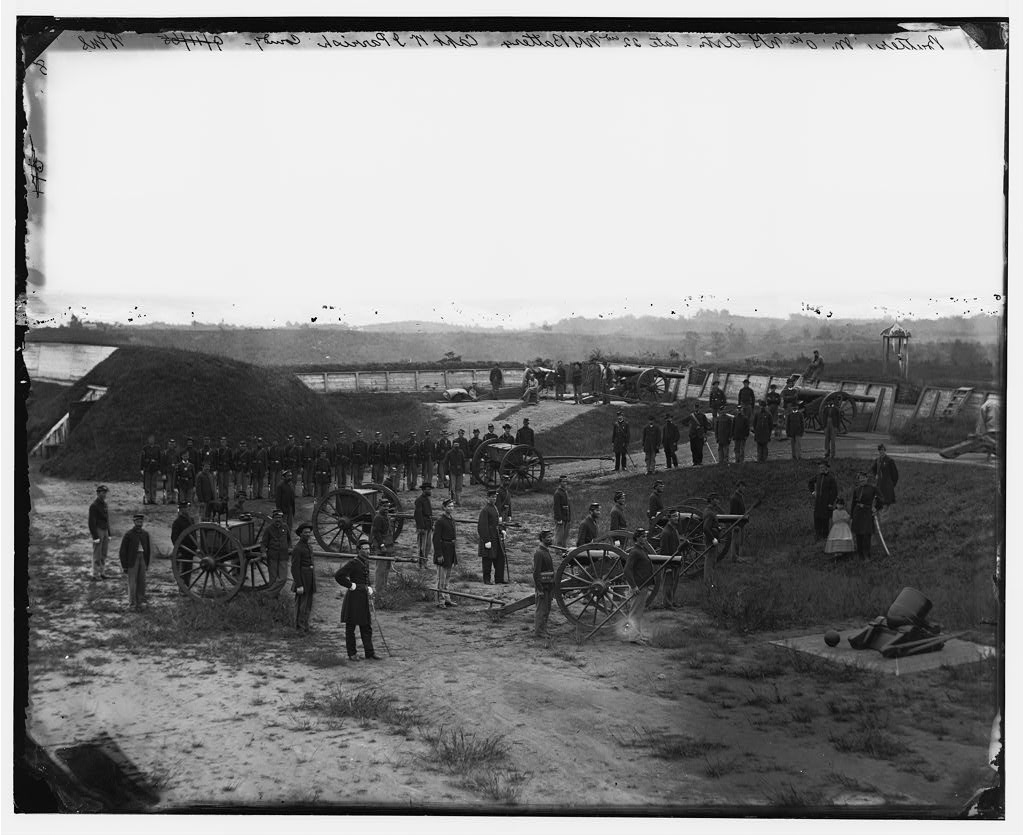

In response to the prevailing anger generated by this incident, Pvt. Hews and the regiment were moved to Fort Ethan Allen. The fort was situated on the opposite side of the Potomac River, to the north of Washington. The soldiers of the 118th regiment devoted their time at Fort Ethan Allen to tirelessly participating in drill activities, unwaveringly grappling with the elements, and steadily combating a sudden surge of illnesses.

William Morris; Civil War Glass Negatives – Library of Congress Catalog: https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/cwp2003000965/PP Original url: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cwpb.04244

It was here at Fort Ethan Allen where Pvt. James Hews met his fate. Around midnight on December 29th, 1862[16] an alarm was sounded to prepare for an attack. The men were ordered to their rifle pits when, “while there a gun in the hands of William H. Stover was discharged Its ball striking J. Hews about the middle of his back by the side of his spine, going upwards through the lung, lodging just under the skin.” [17] Investigation revealed that the men along the picket line had noticed a small incursion of Confederate troops, which was what had set off the alarm.

Pvt. Hews would linger through the night, surrounded by his friends and comrades. His demise would occur later in the day, on the 30th. [18] The company fashioned him a headstone from wood and buried him with full military honors, on the 1st of January 1863. [19] Lieutenant . John H. Smith described the internment as such…

“We have had the painful duty of consigning the remains of poor James to the silent tomb. There were but few dry eyes on the occasion as they all seem to know and feel our loss. We have lost a friend and comrade and some of us a kind neighbor and his kind words and deeds shall ever be fresh in our memories.”[20]

The 118th New York would continue to serve. They would participate in the Siege of Suffolk, as well as the battles of Drury’s Bluff, Cold Harbor, The Creator, Chaffin’s Farm, New Market, Fair Oaks, and Appomattox Court House. Major Cunningham would survive the war with two wounds. Pvt. William H. Stover remained with the regiment until June of 1863, at which point he was recorded as absent due to illness. Subsequently, he was admitted to various hospitals for the remainder of the war and. ultimately discharged from the U.S. General Hospital in April of 1865[21].

Sarah, the wife of Pvt. Hews applied for a widow’s pension in October of 1863. [22] Consequently, she was approved for a monthly allowance of eight dollars. Which, in the year 2024, would be equivalent to approximately one hundred and ninety-five dollars[23]. However, her pension ceased on October 10th, 1866[24], when she remarried James Palmer. Unfortunately, Sarah outlived her second husband as well. Mr. Palmer passed away in 1901[25]. This unfortunate circumstance forced her to reapply for a pension. She was granted one at a rate of twelve dollars per month. As of 2024, this amount would be approximately four hundred and thirty dollars[26]. Sarah’s life came to an end on April 17th, 1915. [27]

Sarah is at rest along with her second husband at Landon Hill Cemetery in Chestertown, Warren County, New York. On the back of her headstone is a cenotaph for Pvt. James Hews. Pvt. Hews is interred at the US Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery in Washington, District of Columbia.

The demise of James Hews, a brave soldier who actively participated in the American Civil War, was a tragic event. Due to a terrible accident that one of his fellow soldiers caused, his life ended abruptly. This unfortunate incident serves as a poignant reminder of the immense grief and sorrow that engulfed the entire war.

[1] Ancestry.com. “James Franklin Hewes in the New York, U.S., Town Clerks’ Registers of Men Who Served in the Civil War, ca 1861-1865,” n.d. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/186054:1964?tid=&pid=&queryId=590cc1eb-0549-4287-a482-6f70397d72d4&_phsrc=JHJ53&_phstart=successSource.

[2] New York, U.S., State Census, 1855 for James F Hews. (n.d.). Ancestry.Com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/1653073418:7181?tid=&pid=&queryId=8a42329a-f003-4781-b696-2d5b0e3193b4&_phsrc=JHJ170&_phstart=successSource

[3] Hews, James F – Fold3 – US, Civil War “Widows’ Pensions”, 1861-1910. (n.d.). Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/file/185244902 P. 57

[4] Three Years With the Adirondack Regiment: 118th New York Volunteers Infantry: Cunningham, John Lovell, 1840- : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet Archive, 1920) P. 13

[5] Hews, James: New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900. (n.d.). Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/315830718

[6] Ibid

[7] Three Years With the Adirondack Regiment: 118th New York Volunteers Infantry: Cunningham, John Lovell, 1840- : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming: Internet Archive, 1920) P. 17

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid P. 21

[10] Ibid P. 22

[11] Ibid P. 22-23

[12] Ibid P. 23

[13] Ibid P. 24

[14] Ibid

[15] Ibid P. 29

[16] Ibid P. 38

[17] James Hews US, Civil War “Widows’ Pensions”, 1861-1910. (n.d.). Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/185244929/hews-james-f-page-14-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910

[18] Hews, James: New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900. (n.d.). Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/315830718

[19] Hews, James Page 16 – US, Civil War “Widows’ Pensions”, 1861-1910. (n.d.). Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/185244932/hews-james-f-page-16-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910

[20] “Hews, James Page 16 – US, Civil War Pensions 1861-1910.” n.d. Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/185244932/hews-james-f-page-16-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910.

[21] “William Stover US, New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900.” n.d. Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/315783439/stover-william-hiram-page-1-us-new-york-civil-war-muster-roll-abstracts-1861-1900.

[22] “Hews, James – US, Civil War Widows’ Pensions, 1861-1910.” n.d. Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/185244907/hews-james-f-page-3-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910.

[23] “Inflation Rate Between 1863-2024 | Inflation Calculator.” n.d. https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1863?amount=8.

[24] “Hews, James Page 33 – US, Civil War Pensions 1861-1910.” n.d. Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/185244965/hews-james-f-page-33-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910.

[25] Ibid

[26] “Inflation Rate Between 1902-2024 | Inflation Calculator.” n.d. https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1902?amount=12.

[27] “Hews, James Page 58 – US, Civil War Pensions 1861-1910.” n.d. Fold3. https://www.fold3.com/image/185245039/hews-james-f-page-58-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910.