In July 1863, the peaceful town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania enjoyed a beautiful day, with little excitement in the town. The residents went about their business in a calm and friendly manner, content with their way of life. However, their tranquility was shattered when a fierce battle erupted, which later became known as the Battle of Gettysburg. This three-day conflict was a significant event in American history, playing a crucial role in shaping the identity and future of the nation.

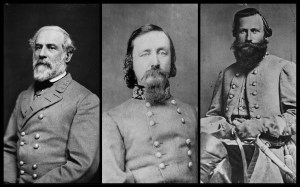

This battle has become the focus of historians, both amateur and professional. Every major decision made during the Battle of Gettysburg has been scrutinized. Blame for the Southern loss has been passed on to Generals Robert E. Lee, George Pickett, and James Ewell Brown Stuart.

This leads us to the question – did the Confederates have a chance of winning this battle? They most certainly did not. The South was destined to lose the battle before those three days in July took place. This was due to the following reasons: overconfidence, the loss of critical leadership, the lack of available fighting men, the deficiency of an industrial complex, southern culture itself, and the fact that the Union forces, especially those from Pennsylvania who were defending their land for the first time during the American Civil War.

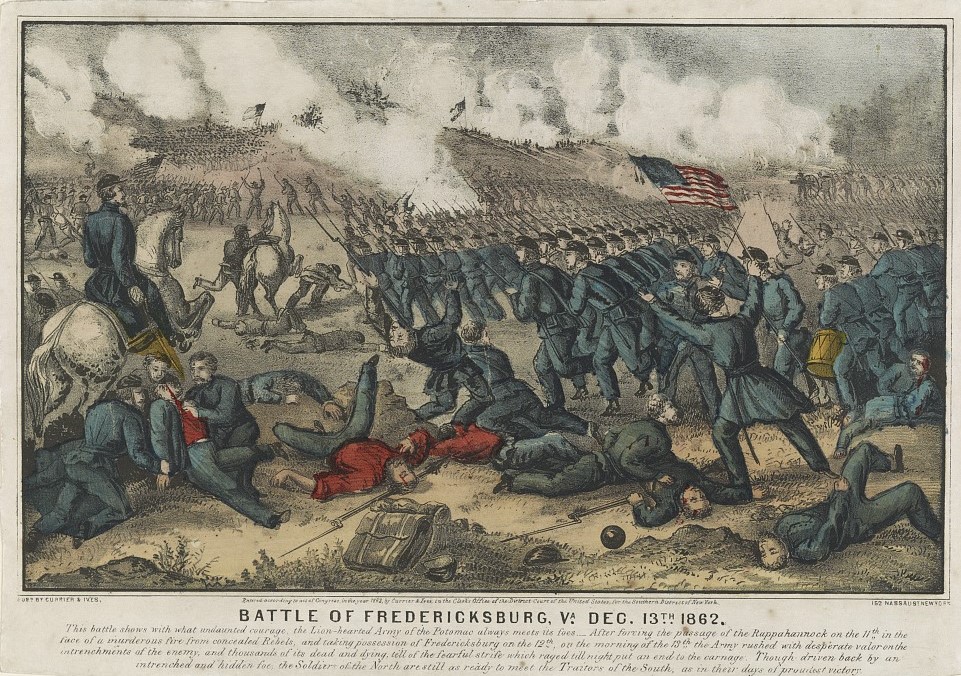

To demonstrate the above points concerning the Confederate’s chance of winning the Battle of Gettysburg, one has to start at the beginning of the war. On April 12, 1861, Confederate guns fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, signaling the beginning of the American Civil War. This was the first in a series of Southern victories, each one bolstering their confidence. During the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862, in Virginia, the Union Army made a grand charge at the stone wall upon Marye’s Heights, only to suffer 12,600 casualties, whereas the Confederates suffered only 5,000.[1]

Then, at the Battle of Chancellorsville during the spring of 1863, another 17,000 Union soldiers fell. Forcing Abraham Lincoln to say, “My God My God, What Will The Country Say.”[2] Riding on the moral boosts of those two victories, Confederate General Lee felt his army was unstoppable and encouraged an invasion of the North. However, high morale is a double-edged sword. Military historian Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Baynes speaks of the importance of a soldier’s morale in his work Morale – A Study of Men and Courage. He says,

“At its highest peak, it is seen as an individual’s readiness to accept his fate willingly even to the point of death, and to refuse all roads that lead to safety at the price of conscience.”[3]

Baynes’s statement speaks to the foolhardiness that overconfident men in battle have. This was shown time and time again by the Southern forces during the Battle of Gettysburg.

One example of Southern overconfidence occurred on July 1, 1863, by Company B of the 26th North Carolina. They were led by Colonel Henry King Burgwyn Jr., a promising young officer and a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute. The 26th was in a desperate fight on McPherson’s Ridge, where they performed repeated charges against the Union forces, which held the high ground. Out of 800 men reported before the day’s fight, only 216 remained; one of the fallen was Colonel Buygwyn himself. [4] Third Colonel John Randolph Lane of the 26th North Carolina later wrote of Buygwyn’s death and the charge, describing it as,

“At this time the colors have been cut down ten times, the color guard, all killed and wounded….The gallant Burgwyn leaps forward, takes them up (the colors), and again the line moves forward; at that instant, he falls with a bullet through both lungs.” [5]

The reckless repeated attacks on well-fortified high ground had cost the southern forces one of their boldest and most promising leaders.

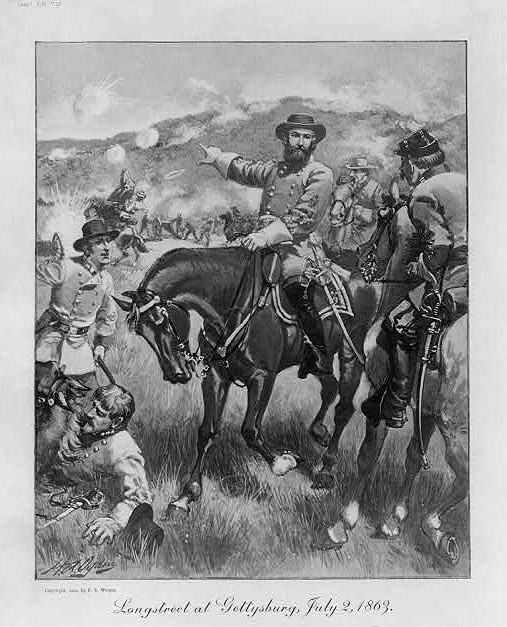

Another example of Southern overconfidence occurred on July 2, 1863. After studying the Federal’s position, the Confederate commanders had a briefing to discuss their future actions at Gettysburg. Feeling his army was unstoppable, General Lee thought this was the time and place to destroy the Federal Army. However, General James Longstreet strongly disagreed and advised General Lee to march south and pick better ground to fight to force an attack. General Lee disregarded Longstreet’s objections and ordered him to attack the left side of the Federal position on Cemetery Ridge and Culp’s Hill. One of the reasons these hills were so important was that artillery could be placed upon them, thus increasing its range. This can be illustrated using the battle at Cemetery Hill.

. Pennsylvania Gettysburg United States, None. [Photographed 1863, july, printed between 1880 and 1889] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014646001/.

Atop the heights of Cemetery Hill, three batteries could be placed to provide a clear view of any force coming from the north or the east. Cemetery Hill had an elevation of 150 feet, which made it the ideal height for firing shots at troops approaching from as far away as six hundred feet. [6]

This had devastating effects on the Confederate forces that tried to attack those heights. These guns commanded the field for all three days of the battle. Major Robert Stiles of the Virginia Light Artillery described the destruction of his artillery by the guns of Cemetery Hill on the second day of the fight by stating:

“Never, before or after, did I see fifteen or twenty guns in such a condition of wreck and destruction as this battalion was. It had been hurled back, as it were, by the very weight and impact of metal from the position it had occupied on the crest of the little ridge, into a saucer-shaped depression behind it, and such a scene as it presented.” [7]

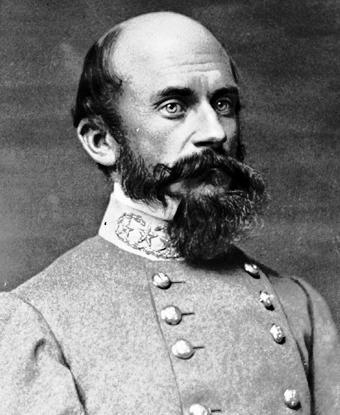

Confederate General Richard Stoddert Ewell’s decision to make a late attack on Cemetery Hill with his whole force indicates Southern overconfidence. This attack, with about 3,500 men, was repulsed by the heavily fortified position, and the Southern force suffered substantial casualties.[8]

Perhaps the most famous example of the audaciousness of the Southern command at Gettysburg is that of the Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble assault on July 3, 1863. After the first two days of fighting at Gettysburg, General Lee decided that his best option was to mass his force and attack the center of the Union line with fresh troops from General Pickett’s division. This attack would entail a 592-yard march under direct enemy fire across open ground. Lee felt his army of northern Virginia was up to the task because he thought they were invincible.[9] After an hour of an artillery barrage, 13,000 Confederate troops stepped out of the woods to begin what would be the last charge for many of them.[10] First Lieutenant John T. James of Company D, 11th Virginia, wrote about his experience in this action. He said:

“After terrible loss to the regiment, brigade, and division, we reached and actually captured the breastworks. Some of them had taken possession of the cannon when we saw the enemy advancing heavy reinforcements. We looked back for ours, but in vain; we were compelled to fall back and had again to run as targets to their balls. Oh, it was hard, too hard to be compelled to give way for the want of men after having fought as hard as we had that day. The unwounded…soon got back to the place where we started from. We gained nothing but glory and lost our bravest men.” [11]

The aftermath of this charge was devastating. Two of the three brigade commanders in Pickett’s division were killed, and the third was severely wounded. In addition, only half of the men who participated in the charge returned to the Confederate lines. [12] This tactical decision by General Lee, based on his men’s high morale and almost unblemished battle record, was beyond disastrous for the Confederate Army and the Confederate States as a whole.

Another aspect that led to the defeat of the Confederate forces during the Battle of Gettysburg was the loss of crucial leadership before the battle. None was more important than the death of Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. Jackson was born in Virginia in 1824. As a teenager, he was appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated in 1846. Jackson was then sent to Mexico, where he was involved in the Mexican-American War. He was brevetted twice for “good conduct” during the battles of Churubusco and Chapultepec. [13] After the war, Jackson became a professor of Philosophy and Artillery at the Virginia Military Institute.

At the American Civil War outbreak, Jackson was appointed to Brigade Commander. During the first battle of Bull Run, the Confederate forces began to break, except General Jackson’s Brigade. When trying to rally his men, Confederate General Bernard E. Bee saw Jackson calmly upon his horse amongst the fray of battle and said, “See there, Jackson, standing like a stonewall, rally on the Virginians!”[14] This is how General Jackson earned the name “Stonewall.” His bravery in the face of danger turned the tide of battle, making it a Confederate victory. Jackson’s subsequent success was during the First Battle of Winchester on May 25, 1862. Using unique tactics, he deployed 5,000 men to delay and distract a much larger force. Author Walton Rawls describes Jacksons actions during this campaign as such,

“Silent as a sphinx, brave as a lion, his unexpected disappearances, and mysterious descents upon the enemy at its weakest points inspired something akin to terror in the breast of the federal soldier.”[15]

These tactics resulted in an overwhelming victory for the Confederate Army at Winchester. Repeatedly, Jackson successfully guided his troops to triumph. At Cedar Run, Jackson drove the Federal Army back with force, and later, in 1862, Jackson captured Harper’s Ferry with 13,000 men and 70 cannons.[16]

In 1863, during the Wilderness Campaign, General Jackson was out scouting the area at dusk when he came upon a picket made up of General William Dorsey Pender’s North Carolinians. He was mistaken for the enemy and shot three times in the left arm, resulting in its amputation.

Upon hearing the news, General Lee remarked, “He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right arm.” [17] These wounds led to General Jackson catching pneumonia, which he succumbed to on May 10, 1863. It was less than three months before the Battle of Gettysburg.[18]

As one can see, General Jackson was a valued commander who General Lee highly trusted. General James Longstreet replaced Jackson. Like Jackson, he graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point and was brevetted during the Mexican War.[19] However, that is where their similarities end. Whereas Jackson was a more aggressive commander, Longstreet tended to err on the side of caution, as seen during the Battle of Gettysburg. At Gettysburg, General Longstreet insisted that the Confederate force leave after the first day and regroup before heading to Washington. However, General Lee wanted to keep up the fight and take on the Union forces while they had them in their sights.

Lee hoped to strike what he thought would be one final blow and end the war. This point of contention was hotly discussed between the two commanders and is still debated today. Another big question historians ask is, what, if anything, would Jackson have done differently if still alive? Perhaps he would have deployed the same maneuvers he did at Winchester and used his brigade to strike the Union army at will, striking fear into them and thus avoiding the fated meeting on the fields of Pennsylvania. Or if they did meet at Gettysburg, would Jackson and Lee devise a joint plan that would have destroyed the Union and ended the war? We will never know the answer to that question.

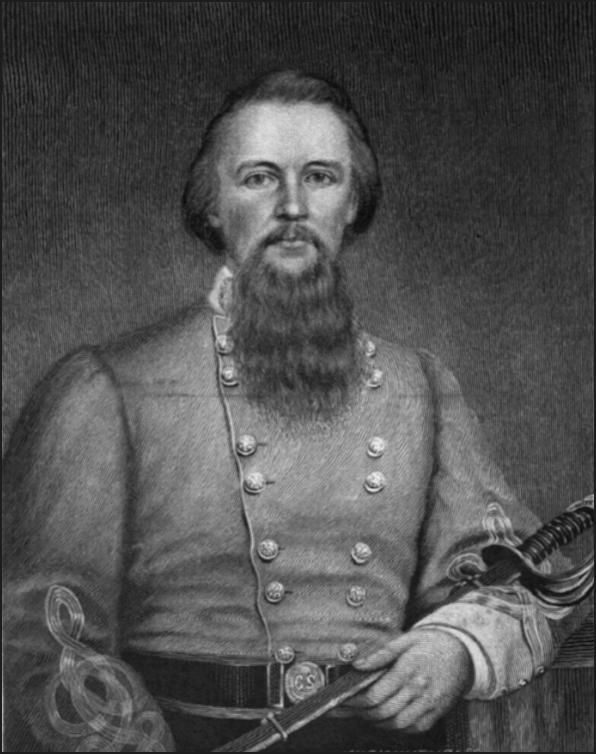

Another general who was a severe loss to the Confederacy before the Battle of Gettysburg was Brigadier-General George Burgwyn Anderson. Anderson was a North Carolina native and graduated 10th in his class at The United States Military Academy at West Point in 1852. After graduation, he had a successful career as a Cavalry officer. He resigned his commission in 1861 to serve the Confederate States of America.[20] Anderson’s most prominent and boldest display of leadership took place during the Battle of Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1862, where

“out of 520 rank and file which the regiment carried into action, 462 were killed or wounded, and out of 27 commissioned officers, all but one were killed or wounded. This was not a foredoomed forlorn hope or a charge of a ‘Light Brigade,’ but surpassed any such recorded in history, both in loss and achievement, for they went in to win and did win. During this fight, Colonel Anderson seized the colors of the Twenty-seventh Georgia and dashed forward, leading the charge. Though his men, cheering wildly as they followed, losing scores at every step, their courage was irresistible, and Anderson planted the colors on the stubbornly defended breastworks. This was witnessed by President Davis, who at once promoted Anderson to brigadier-general.”[21]

As this quote shows, Brigadier-General Anderson was a brave and inspirational leader to his men. However, this was not his only attribute which benefited the Confederacy. During the Seven Days Battle in the summer of 1862, “He was conspicuous for skill in detecting the weak points of the enemy and boldness and persistence in attack.”[22] Later, in 1862, Brigadier-General Anderson led another bold charge during the battle of Malvern Hill, where he was wounded. During the Battle of South Mountain in the fall of 1862, his division was outnumbered and held off half of General McClellan’s Union force.[23] A few days later, during the Battle of Sharpsburg, also known as The Battle of Antietam, Anderson again gallantly led his men in a charge at what was to be known as the “Bloody Lane.” He was wounded in the ankle and died of infection a month later in Raleigh, North Carolina.[24]

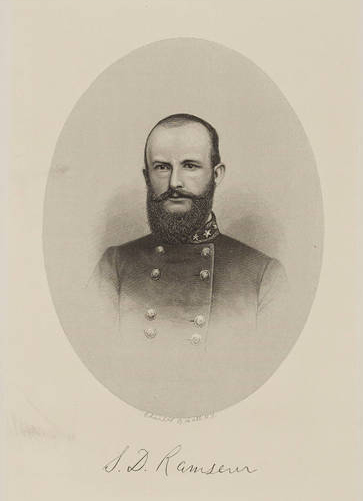

Upon his death, Brigadier-General Anderson was replaced by Major-General Stephen Dodson Ramseur. Ramseur was also a United States Military Academy graduate at West Point. However, he was only 14th in his class. [25] The Battle of Fredericksburg, in December of 1862, was General Ramseur’s first chance at commanding his new brigade. He did so with success. He was also victorious in the spring of 1863 at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Before The Battle of Gettysburg, these were the only two battles in which he served as a Brigade Commander. Thus making him one of the least experienced officers in the field.

On July 1, 1863, the first day of the Battle of Gettysburg, Brigadier General Ramseur’s brigade successfully pushed back the Union line before the Federals completely routed the Confederate forces. When reviewing July 2 in his after-action report, Ramseur said:

“Remained in line of battle all day, with very heavy skirmishing in front. At dark, I received an order from Major-General Rodes to move by the right flank until Brigadier-General Doles’ troops cleared the town and then to advance in line of battle on the enemy’s position on the Cemetery Hill. I was told that the remaining brigades of the division would be governed by my movements. I obeyed this order until within 200 yards of the enemy’s position, where batteries were discovered in position to pour upon our lines direct, cross, and enfilade fires. Two lines of infantry behind stone walls and breastworks were supporting these batteries. The strength and position of the enemy’s batteries and their supports induced me to halt and confer with General Doles, and, with him, to make representation of the character of the enemy’s position, and ask further instruction. In answer, received an order to retire quietly to a deep road some 300 yards in the rear and be in readiness to attack at daylight; withdrew accordingly.” [26]

This over-cautiousness would not have been shown by his predecessor, Brigadier General Anderson, who, as mentioned before, had an eye for finding the weakness in the enemy and exploiting it to his advantage and ultimate victory. Ramseur’s lack of skill, knowledge, and ambition cost his brigade dearly on the third day of battle at Gettysburg. Ramseur wrote in his after-action report, about July 3rd saying,

“remained in line all day, with severe and damaging skirmishing in front, exposed to the artillery of the enemy and our own short-range guns, by the careless use or imperfect ammunition of which I lost seven men killed and wounded. Withdrew at night and formed line of battle near Gettysburg, where we remained on July 4.”[27]

Not only did this cost Brigadier General Ramseur’s brigade the lack of gaining the high ground, but it also cost the Confederate Army. This is because the high ground commanded the field by being able to pour fire down at the enemy from a long range. The loss of Brigadier General Anderson at Antietam proved costly at the time as well as months later at Gettysburg.

Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest once said, “The key to victory is to get there first with the most.”[28] The southern forces had little issue with the former. However, the latter part of General Forrest’s statement was nearly impossible for the South, since they had less than one-third of the available manpower of the North.[29] This issue would get worse as the war went on. The southern forces would lose 2,000 men killed and another 9,000 wounded at Antietam. [30] At Fredericksburg, a Confederate victory resulted in about 5,000 Southern casualties.[31] At Chancellorsville, they lost 13,000 killed, wounded, and missing again in what is to be considered a Confederate victory.[32]

The Union also suffered heavy losses in all of these battles, but the difference was they could replace them. This was because the northern states were more populated. The Northern states were also receiving a continuous influx of immigrants from Europe, who were provided with weapons a uniform, and instructed to participate in the fighting for their adopted nation.

Before the Battle of Gettysburg, the Union had greater numbers of troops compared to the Confederate forces. Approximately 95,000 men made up the Union’s troop strength, while the Confederacy had just 67,000 soldiers present on the battlefield. [33] During the first two days at Gettysburg, the numbers for the Confederacy would diminish even more. During the fight for Cemetery Hill, on the first day, the 26th, North Carolina alone lost 549 out of its 843 men.[34] After the engagement at Little Round Top on the second day, the Confederate forces lost 1,200 men as opposed to only 500 Union troops.[35] During the fight for the Wheatfield, an Ohio regiment reported that the Confederate bodies were stacked so high and thick they could not avoid trampling upon them in their pursuit of the retreating Louisiana Tigers.[36] All of these examples are losses that the Confederacy could not afford.

General Lee opted to concentrate his forces and launch an attack on the Union line in the middle, partly as a result of numerous Confederate losses. This conclusion would result in the infamous Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble charge on the third day of Gettysburg. General Lee would outnumber the Union by massing his forces and having 13,000 men attack 7,000.[37] Lee didn’t fully comprehend the strength of the entrenched force with heavily fortified positions, similar to his own force at Fredericksburg on Marye’s Heights. That led to the Union line being cut down during that engagement. The Pickett,Pettigrew, Trimble assault had the same result, with Pickett’s division loosening forty percent of its strength. The Confederate army also lost many commanders, including Generals Armistead, Garnett, and Kemper.[38]

After this disastrous maneuver, General Lee told Major General Pickett, “You and your man have covered yourself with glory.” Pickett replied, “Not all the glory in the world, General Lee can atone for the widows and orphans this day has made.”[39] This response to Lee by Pickett shows the waste of misutilized manpower that resulted from this decision, an operation based on General Lee’s use of the available forces. Lee went into the battle with the numbers working against him.

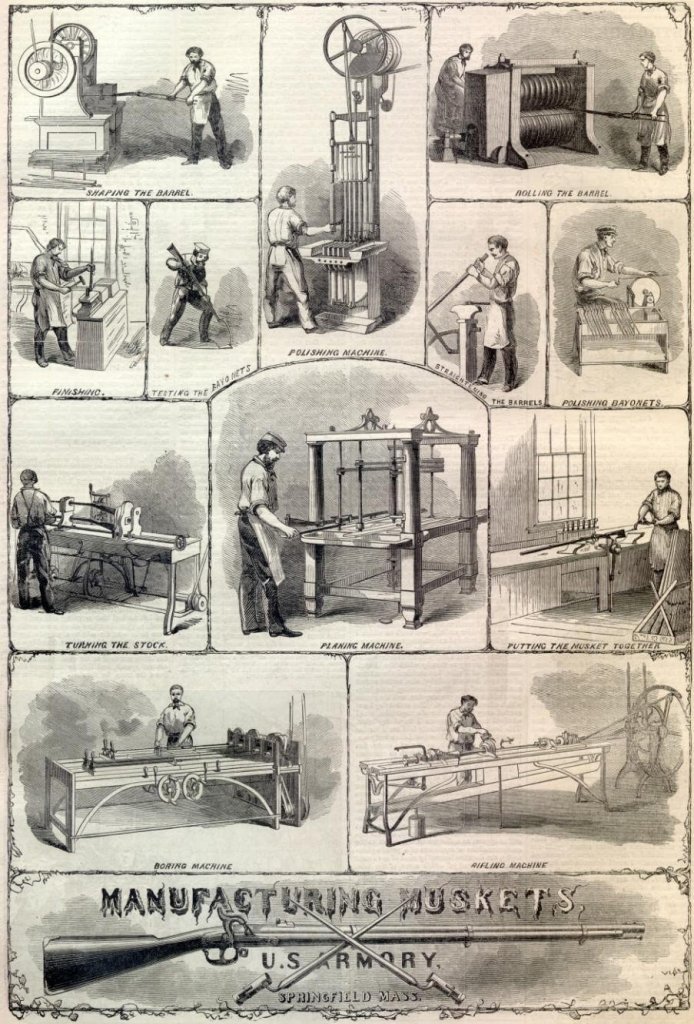

The southern states not only had a shortage of able-bodied men for combat but also lacked the industrial capability of the North. Unlike the northern states, which had numerous factories like the Springfield Armory, the South struggled to produce arms and munitions. The northern states produced 32 times more firearms than the southern states. This is to say that the North produced 3,200 firearms for every 100 made in the South.[40] This was a problem for the southern states because it forced them to obtain many of their armaments from outside the country. Any loss of munitions or a means to produce them was disastrous to the Confederacy’s efforts.

The effects of lack of munitions can be seen during the Battle of Gettysburg. During the artillery barrage that took place before the Pickett, Pettigrew, and Trimble assault on July 3, 1863, one hundred and forty-three guns opened fire in an effort to soften the Union line. The intended effect however was not achieved by the aforementioned actions. Several weeks earlier, the Richmond arsenal, a major producer of fuses for cannon projectiles, had exploded and been obliterated. As a result, the Confederacy had to resort to using untested fuses with longer burn times from Charleston, South Carolina. These fuses led to the artillery pieces overshooting the Union line, resulting in less damage and compelling the courageous Southern soldiers to march into inevitable doom and eternal glory.[41]

War materials were not the only thing lacking in the Southern ranks. They also missed the comforts of home, such as buttons for their uniforms and cotton to repair them. Additionally, they missed spices, food items, and fresh water. The North had sutlers who followed them around and provided them with all sorts of provisions, and the South did not. Instead, the Confederate troops could purchase these items or find them in the towns they came upon in their invasion of the North.[42]

The Gettysburg campaign exacerbated the South’s need for such items. The long forced marches drew them further away from their limited supply train. These maneuvers made by the Confederate Army were an exercise in misery, as they marched 30 miles or so a day with pounds of equipment, including their packs, blanket roll, and weapons. A soldier describes the men after such a march as “footsore, weary, supperless, and half-sick…. {They} lay down in their wet clothes and grimy condition to sustain the same ordeal tomorrow.”[43] As a result, the town of Gettysburg looked like an oasis for the men and their commanders. This is one of the reasons the town was chosen to be occupied. Perhaps if the Southern forces had been better supplied, they may have made it to Washington D.C. and avoided the battle of Gettysburg altogether.

Another aspect that negatively affected the Southern forces during the Battle of Gettysburg was their own culture. In his work, Organizational Culture and Leadership, Professor Edgar Henry Schein defines culture as “A here and now dynamic and phenomenon and coercive background that influences us in multiple ways.”[44] One aspect of Southern culture that influenced them was the idea of aristocratic chivalry created by slave-owning. Many Southerners believed they were descended from the Cavaliers of old. Professor of history Rollin G. Osterweis describes this belief in his work, Romanticism and Nationalism in the Old South. He states,

“Persons belonging to the blood and race of the reigning family recognized as Cavaliers directly descended from the Norman-Barrons of William the Conqueror, a race distinguished in its earliest history for its warlike and fearless character, a race in all times since renowned for its gallantry, chivalry, honor, gentleness, and intellect…The Southern people came from that race.”[45]

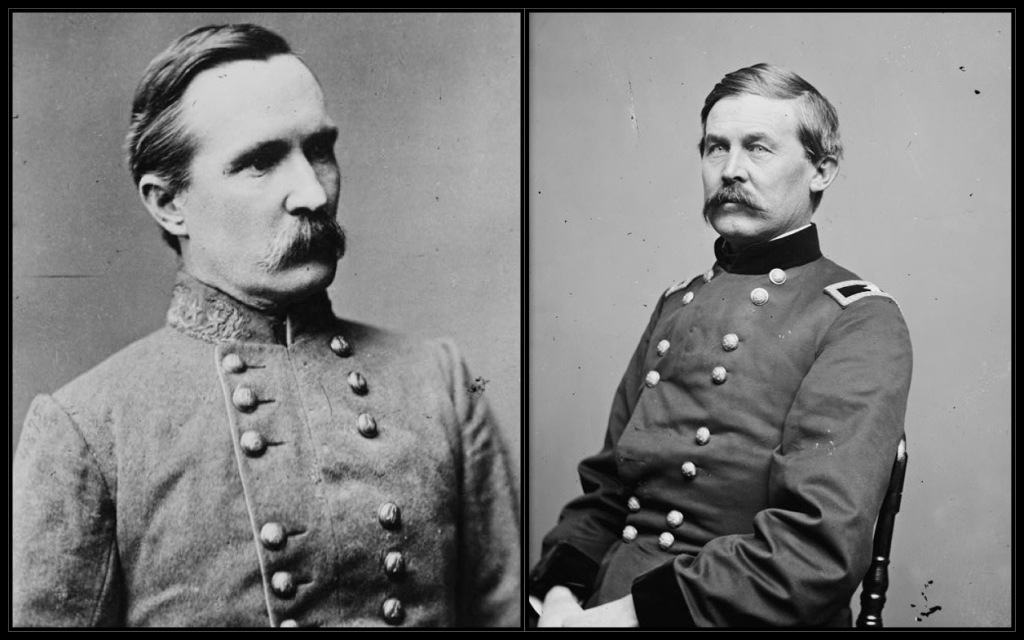

General James Ewell Brown Stuart, also known as JEB, fully embraced this philosophy. In 1854, he graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point. He had a successful career as an Indian fighter. As a member of a U.S. Military detachment, he also accompanied General Lee in halting John Brown’s raid on the arsenal at Harpers Ferry. His daring, cavalier attitude and thirst for adventure, coupled with his heroic actions in battle and composure under fire, earned him the admiration of his men. [46]

The crucial role of cavalry in the American Civil War encompassed not only serving as a swift strike force capable of altering the course of battle, but also as scouts with the ability to ride undetected around the enemy, tally troop numbers, and provide intelligence on enemy movements. An infantry commander would be left in a perilous situation without this vital service, rendering them blind to the battlefield. General Lee relied on this intelligence very much. American historian Douglas Southall Freeman says, “Lee’s strategy was built, in large part, on his….intelligence reports…facilitated more by Stuart and Stuarts’ scouts than anything else.”[47]

On June 22, 1863, General Lee issued orders to General Stuart, stating that he was to guard General Ewell’s right flank, “keep him informed of all enemy movements, and, if possible, ride across the Potomac to go east or west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.”[48]General Stuart saw these orders as an opportunity to head northward on a search for glory, rather than just crossing the Potomac as instructed. His bold and cavalier attitude, as well as his desire for combat action, fueled his decision. During Stuart’s raid, General Lee had no contact with him, leaving Lee unaware of General Hooker’s Federal forces’ movements and troop numbers. This lack of communication also left Lee in the dark during the initial day of the Battle at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863. When the Confederate forces first met the Union Army, Lee thought this was just a small detachment of Union forces. He fought them with uncertainty by not fully committing his entire force, which at the time outnumbered his enemy. He told General Longstreet, “Without Stuart, I do not know what to do.”[49] Perhaps, if Lee was more confident and had his numbers verified by Stuart’s Cavalry, he would have brought up all his force and pushed the Federals back on that first day. This may have changed the result of the battle.

Furthermore, the lack of reconnaissance hurt Confederate General Heath as he marched blindly into an ensnarement perpetrated by Union General Buford on the first day of battle. Health kept pushing men up front, thinking that Buford would engage them and retreat.

However, the famed Union Iron Brigade came up and laid waste to the Confederate troops, who suffered heavy casualties that they could not afford.[50] General Stuart arrived at Gettysburg mid afternoon on July 2nd with a few captured wagons to show for his poor decision.[51] By then, it was too late; the Union had the high ground, and the Battle of Gettysburg was all but lost for the Confederacy.

Their defeat at Gettysburg was also influenced by Southern culture through their tendency to use indirect language and their preference for politeness when giving orders. The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 5: Language describes this phenomenon by saying,

“A slightly different dimension of politeness is the degree to which one communicates in a ‘direct’ fashion. Southerners are notoriously indirect, a classic negative politeness strategy. Such indirectness can appear in the overall interaction structure, as in the time spent before getting to the main business of a conversation. A negative politeness strategy is probably most clearly demonstrated as “indirect speech acts.”[52]

This failure to communicate can be seen in General Lee’s orders to General Ewell to take Cemetery Hill “if practicable.” [53] This ambiguous order left General Ewell to decide what to do. In the end, Ewell chose not to take the hill, leaving it open for the Union to occupy and thus setting them up on the high ground for the rest of the battle. Perhaps the outcome would have been different if General Lee had been more direct and had ordered Ewell to take the hill instead of being polite. As one can see, the very core of the Southern soldier and their culture affected the battle in a way that hurt their cause and resulted in defeat.

Before Lee invaded the North, the Confederate forces had enjoyed the benefit of fighting in their backyard and defending their land; this gave them a home-field advantage that had many benefits, none more important than a strong sense of pride and urgency to defend what was theirs. Southern Politician John Slidell wrote of this benefit, saying,

“We shall have the enormous advantage of fighting on our territory and for our very existence . . . All the world over, are not one million men defending themselves at home against invasion stronger in a mere military point of view than five million [invading] a foreign country?”[54]

During the Battle of Gettysburg, their advantage was lost, and the North gained it as the situation was reversed. Historian Bell Irvin Wiley, in his work The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union, quotes a Union surgeon who noticed this dramatic shift in the Federal’s fighting spirit:

“Our men are three times as enthusiastic as they have been in Virginia, The idea that Pennsylvania is invaded and that we are fighting on our own soil, proper, influences them strongly. They are more determined than I have ever before seen them.”[55]

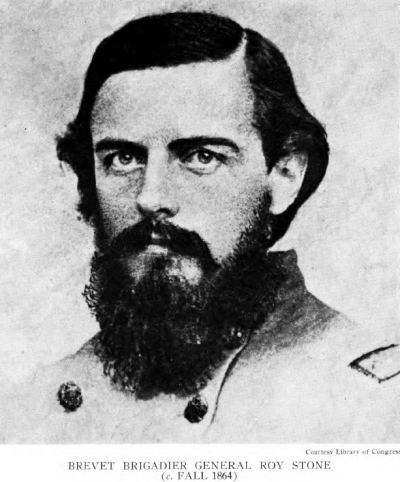

Colonel Roy Stone’s brigade of around 1,300 Pennsylvanians provides the best illustration of the Federals defending their homes, particularly with their actions in and around McPherson Woods on the initial day of the battle.[56] In his report, he writes about how his brigade faced overwhelming odds and held the Confederate forces at bay, saying,

“No language can do justice to the conduct of my officers and men on the bloody” first day; “to the coolness with which they watched and awaited, under a fierce storm of shot and shell, the approach of the enemy’s overwhelming masses; their ready obedience to orders, and the prompt and perfect execution, under fire, of all the tactics of the battle-field; to the fierceness of their repeated attacks, on to the desperate tenacity of their resistance. They fought as if each man felt that upon his own arm hung the fate of the day and the nation.”[57]

In holding their position, the men of Stone’s brigade suffered a considerable loss as 853 men were killed, wounded, or missing, but they were willing to give their last full measure because their blood would be spilled on the soil of their native state.[58] This action held the Confederates in check, keeping them from attaining the high ground that would be so crucial to the Union’s success during the second day of battle and the entire Battle of Gettysburg,

The Battle of Gettysburg cost the Confederacy deeply. After the three-day engagement, they had lost 24,000 men. This was about one-third of the troop strength Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia brought into battle,[59] An irrecoverable loss that led to their inevitable end. After the battle, General Lee spoke to his generals, saying that it was all his fault. However, this was not the case, as the mistakes and circumstances before the battle led to their defeat. Their overconfidence led to imprudent decisions and needless casualties. Crucial leadership’s absence led to commanders lacking experience, causing them to hesitate. General Longstreet’s lack of trust from General Lee resulted in his alternate plan falling on deaf ears. The lack of available fighting men caused Lee to perform a mass charge with most of his available forces on what he thought was the weakest point of the Union line. This resulted in a desperate charge, costing him almost his entire army.

The South’s lack of an industrial complex caused them to use inferior munitions and adopt a forage strategy, making Gettysburg an attractive place to stage and regroup.

Lastly the South was influenced by southern culture. The concept of the Cavalier was deeply embedded, resulting in their top cavalry leader, James Ewell Brown Stuart, participating in a raid for his own benefit, which resulted in General Lee being deprived of intelligence reports.Furthermore, this culture was based on polite speech, leading to misinterpreted orders, which left the Southern forces vulnerable on the second day of battle. For these reasons, the South lost the Battle of Gettysburg and, ultimately, the war.

What started as a lovely day in July 1863 in the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, ended up as three days that fulfilled the fate of the South and changed the nation.

[1] McPherson, James. Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992. 303

[2]Ibid, 321

[3] Baynes, John Christopher. Morale : a Study of Men and Courage. Garden City N.Y: Avery, 1988. 87

[4] Wilson, Clyde Norman. The Most Promising Young Man of the South : James Johnston Pettigrew and His Men at Gettysburg. Abilene, Tex.: McWhiney Foundation Press, 1998. 63

[5] Davis, Archie K. Boy Colonel of the Confederacy : the Life and Times of Henry King Burgwyn, Jr. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1985. 329

[6] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg : the Last Invasion. First ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. ?

[7] Stiles, Robert. Four Years Under Marse Robert. 3d ed., 8th thousand. New York: Neale, 1904., 34

[8] Nofi, Albert A. The Gettysburg Campaign, June-July 1863. 3rd ed. Conshocken, PA: Combined Books, 1997. 136

[9] Rollins, David and Shultz, Richard. Measuring Pickett’s Charge. n.d. http://www.gdg.org/Gettysburg%20Magazine/measure.html (accessed 04 26, 2014).

[10] McPherson, James. Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992. 327

[11] Georg, Kathleen R. Nothing but Glory : Pickett’s Division at Gettysburg. Hightstown, NJ : Longstreet House, 1987. 149

[12] McPherson, James. Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992. 329

[13] Rawls, Walton. Great Civil War Heroes and Their Battles. New York, NY: Abberville Press, 2011. 226

[14] Ibid, 227

[15] Ibid, 227

[16] Ibid. 228

[17] Carlisle, Rodney P & Kirchberger, Joe H. Civil War and Reconstruction. New York, NY : Facts on File , 2008. 380

[18] Rawls, Walton. Great Civil War Heroes and Their Battles. New York, NY: Abberville Press, 2011. 229

[19] Ibid, 245

[20] Evans, Clement A. Confederate Military History, a library of Confederate States Military History: Volume 4, North Carolina Atlanta, GA: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. 289

[21] Ibid, 290

[22] Ibid

[23] Ibid

[24] Pippen, Craig. George B. Anderson Bio-Sketch. 2013. http://www.ncscv.org/george-burgwyn-anderson (accessed 05 02, 2014).

[25] Evans, Clement A. Confederate Military History, a library of Confederate States Military History: Volume 4, North Carolina Atlanta, GA: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. 341

[26] Ramseur, S.D. Report of Brig. Gen. S. D. Ramseur, C. S. Army, commanding brigade. http://www.civilwarhome.com/ramseurgettysburgor.htm (accessed 5/ 3/ 14)

[27] Ibid

[28] Alexander, Bevin. How Great Generals Win . New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2002. 23

[29] McPherson, James. Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992. 171

[30] Ibid, 286

[31] Ibid, 303

[32] Ibid, 321

[33] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg. New York: Alfred A. Knoph, 2013. 160

[34] Ibid, 196

[35] Cross, David F. “Battle of Gettysburg: Fighting at Little Round Top.” America’s Civil War Magazine, July 1999: retrieved from http://www.historynet.com/little-round-top#tabs-13685314-0-0. 5/3/14

[36] Thackery, David T. A Light and Uncertain Hold: A History of the Sixty-Sixth Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Kent, Ohio : Kent State Univ Press, 1999.62

[37] Hess, Earl J. Pickett’s Charge: The Last Attack at Gettysburg. Chapel Hill, NC : The University of North Carolina Press, 2011. 222

[38] Smith, Carl. Gettysburg 1863 high tide of the confederacy. Westport, CT: Osprey Publishing, 2004. 104

[39] Guelzo, Allen C. Gettysburg. New York: Alfred A. Knoph, 2013. 428-29

[40] Arrington, Benjamin T. Industry and Economy during the Civil War. 4 26, 2014. http://www.nps.gov/resources/story.htm?id=251 (accessed 5 4, 2014).

[41] Oester, Dave. Ghosts of Gettysburg: Walking on Hallowed Ground. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, Inc, 2007. 77

[42] Coddington, Edwin. The Gettysburg Campaign A Study in Command. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1979. 159

[43] Ibid, 79

[44] Schein, Edgar H. Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, 2010. 3

[45] McPherson, James. Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992. 53

[46] Robinson, Warren C. Jeb Stuart and the Confederate Defeat at Gettysburg. Lincoln, NE: The University of Nebraska, 2007. 34-36

[47] Robinson, Warren C. Jeb Stuart and the Confederate Defeat at Gettysburg. Lincoln, NE: The University of Nebraska, 2007. 39

[48] Ibid, 51

[49] Ibid, 120

[50] Robinson, Warren C. Jeb Stuart and the Confederate Defeat at Gettysburg. Lincoln, NE: The University of Nebraska, 2007. 124

[51] Ibid, 130

[52] Montgomery, Michael & Johnson, Ellen. The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 5: Language. Chapel Hill, NC : The University of North Carolina Press , 2007. 172

[53] Cole, Phillip M. Command and Communication Frictions in the Gettysburg Campaign. Orrtanna, PA: Colecraft Industries , 2006. 69

[54] McPherson, James. Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992. 187

[55] Wiley, Bell Irvin. The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union. Baton Rouge, LA : Louisiana State University Press, 2008. 283

[56] Vanderslice, John M. Gettysburg, then and now, the field of American valor; where and how the regiments fought, and the troops they encountered; an account of the battle, giving movements, positions, and losses of the commands engaged;. Philadelphia, PA: G. W. Dillingham co, 1897. 57

[57] Stone, Roy Col. “Report of Col. Roy Stone, One hundred and forty-ninth Pennsylvania Infantry, commanding Second Brigade.” Gettysburg Order of Battle. 1863. http://www.civilwarhome.com/stonegettysburgor.htm (accessed 5 17, 2014).

[58] Vanderslice, John M. Gettysburg, then and now, the field of American valor; where and how the regiments fought, and the troops they encountered; an account of the battle, giving movements, positions, and losses of the commands engaged;. Philadelphia, PA: G. W. Dillingham co, 1897. 57

[59] McPherson, James. Ordeal By Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992. 329