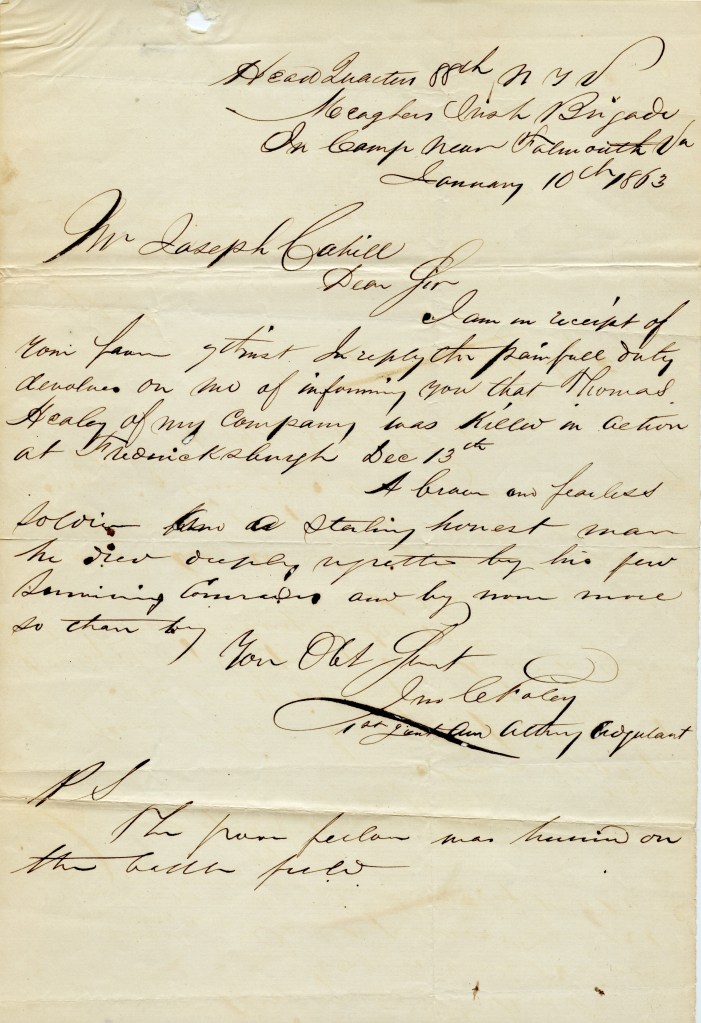

In the somber shadows of war, letters often serve as poignant reminders of both sacrifice and duty. This letter, penned by 1st Lieutenant and Acting Adjutant John C. Foley of the 88th New York Volunteer Infantry, bears the heavy news of loss amidst the chaos of the Battle of Fredericksburg. This correspondence was addressed to Mr. Joseph Cahill and reveals the personal toll of conflict. It informs him of the premature death of Private John Healey, a brave soldier whose life ended on the battlefield. Through Foley’s heartfelt words, we glimpse the profound grief and camaraderie that defines the soldier’s experience, as well as the enduring impact of such tragedies on families and communities back home.

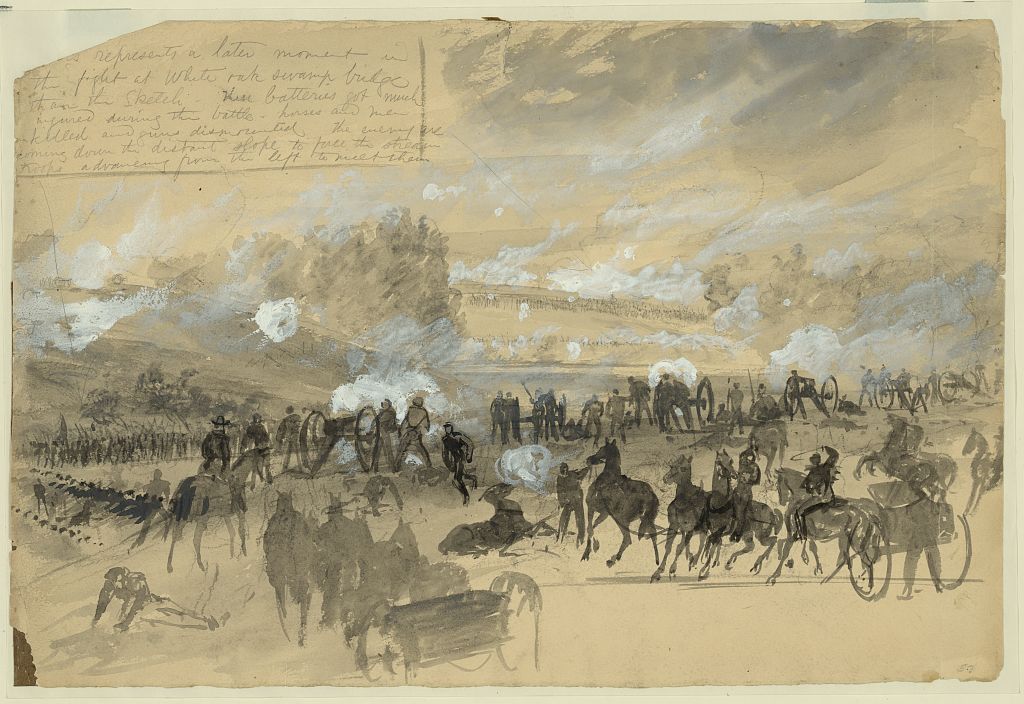

The author of this letter, John C. Foley, was born in Tipperary, Ireland, around 1836.[1] At thirteen, he immigrated to America aboard The Alice Wilson and lived with his family in Brooklyn, New York.[2] According to the 1860 United States Census, Foley worked as a clerk. He enlisted on September 1, 1861, after the outbreak of the American Civil War. By October, they commissioned him as a 1st Lieutenant of Company “D”, 88th New York Volunteers.[3]. 1st Lieutenant Foley and the 88th would leave New York on December 16.[4] The 88th arrived in Washington, D.C, where they performed duty in the city’s defenses at Camp California near Alexandria. They were later attached to Meagher’s Brigade, Sumner’s Division, Army of the Potomac. In April 1862, the command ordered 1st Lieutenant Foley and the 88th to the Peninsula, Virginia. Later that month, Foley and his men would engage in their first action during The Siege of Yorktown. In the next few months, they would be engaged in The Battles of Fair Oaks, Gaines Mill, Savage Station, White Oak Swamp Bridge, and Glendale. During the Battle of White Oak Swamp Bridge, 1st Lieutenant Foley’s company took heavy artillery fire. David Power Conyngham described the scene in The Irish Brigade and Its Campaigns: With Some Account of the Corcoran Legion and Sketches of the Principal Officers.

“Each part of the field and each portion of the day has its incidents. Around-shot ricochets strikes with a dull, heavy sound the body of a fine brave fellow in the front rank and bounds over him. He is stone dead; the two men on each side of him, touching him as they lay, rise up, lift the stiff corpse, lay it down under a tree in the rear, cover his face with his blanket, come back to the old place, lie down on the same old fatal spot, grasp the musket again without saying a word. How brave, how cool, how dauntless these men are! A hundred thousand of these Celts would- but no matter: what is speculation here? That shell came very near-scattered a portion of it strikes Lieutenant Foley, of the Eighty-eighth, stuns him for a time; he recovers, will recover.”[5]

The 88th would continue to fight at Malvern Hill and the Battle of Antietam. In the after-action report referencing Antietam, Lieutenant-Colonel Patrick Kelly, Commanding Officer of Eighty-eighth New York, states the following.

“the Irish Brigade, of which my regiment formed a part, crossed the Antietam Creek, and advanced in column until within sight almost of the enemy. The brigade then formed line of battle, and, after tearing down a fence, got into action at once. Shortly after this, General Meagher rode up along the line, encouraging the men, until his horse was killed and he got a severe fall….I know not exactly how long we were in action, but we were long enough there to lose, in killed and wounded, one-third of our men (bringing in 302 and losing 104). When relieved by the Fifth New Hampshire, I reported to General Richardson by order of one of his aides. On approaching the general, he said, “Bravo, Eighty-eighth; I shall never forget you.” The rank and file responded by giving him three hearty cheers. He (the general) then placed me in command of the One hundred and eighth New York and ordered us to support a battery a little in advance of where we were previously engaged and remained there during the night and next day. With regard to the conduct of the officers of the Eighty-eighth on that occasion, I must say that they acted to my entire satisfaction – so much so that I cannot say one is braver than another. I have the same to say of the rank and file.”[6]

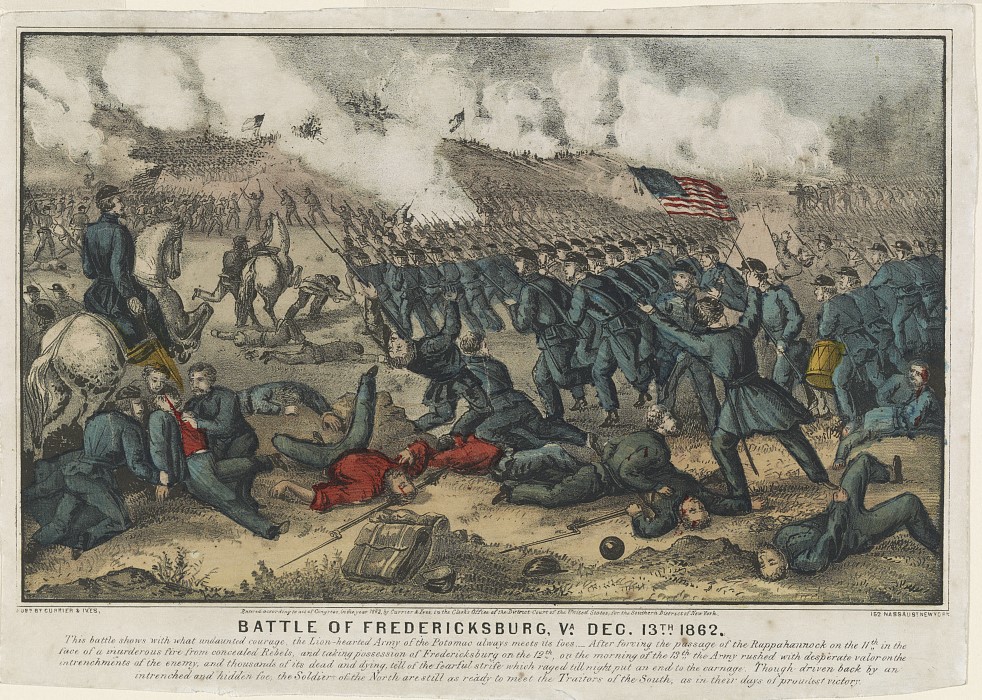

The next test for 1st Lieutenant Foley and the 88th was the Battle of Fredericksburg. Sadly, this action ended the life of the subject of this letter, Private Thomas Healey. Healey was born in Ireland around 1836 and, by the time of the American Civil War, lived in Brooklyn, New York, and worked as a painter.[7] Healey joined the military on November 30, 1861, following the onset of the American Civil War. He officially enrolled in “D” Company of the 88th New York State Volunteers on the same day.[8] Private Healey was as battle-tested as the rest of the 88th New York before the Battle of Fredericksburg.

On the morning of December 12, “D” Company of the 88th New York crossed the pontoon bridge and arrived in Fredericksburg. They would stay in the town for the night before advancing to the front lines. In his report, Colonel Patrick Kelly of the Eighty-Eighth New York Infantry details the following day’s combat events.

“Again, on Saturday morning, the men were under arms and marched about a half a mile to the right of the position

they occupied the night previous, where they formed line of battle in connection with the other regiments of the brigade, between the hours of 10 and 11 a.m., as near as I can judge. We marched by the right flank, crossing the mill-race on a single bridge, where we filed to the right and reformed line of battle under a terrific enfilading artillery fire from the enemy. We then advanced in line of battle under a most galling and destructive infantry fire, crossed two fences, and proceeded as far as the third fence, where my men maintained their position until their ammunition was exhausted and more than one-half of the regiment killed and wounded. At this fence Colonel Byrnes, of the Twenty-eighth Massachusetts Volunteers, and myself agreed to go over the field and collect the remnants of our regiments, which we did, meeting in the valley near the mill-race. Marching from thence to the street from which we started, we reported with our regiments and colors to Brigadier-General Meagher. He (General Meagher), being under the impression he had permission to remove his wounded to the other side of the river so as to avoid the fire of the enemy, ordered those men of his brigade who were still unhurt to convey their wounded comrades over, which they did, and bivouacked there for the night. Early next morning, in accordance with orders from General Hancock, we recrossed the river and took up the position we occupied the night previous, holding the same until the night of December 15, when we recrossed the river and proceeded to the camp which we left Thursday, December 11, where we now are.I cannot close this report without saying a few words with regard to the officers and men of my regiment. That the officers did their duty is fully evident from their loss, having 4 killed and 8 wounded. The gallantry and bravery of the men is too plainly visible in their now shattered and broken ranks, having lost on that day about 111 killed and wounded. * [9]

Private Patrick Healey, who now rests in Fredericksburg National Cemetery, was one of the soldiers who lost their lives that day. 1st Lieutenant Foley, although emerging from the battle unharmed, carried substantial emotional burdens as he buried his friend Lieutenant Richard P. King, who lost his life during the fight.[10]

Foley also had the heartbreaking task of informing the families of the fallen, an example of which is in the aforementioned letter to Mr. Cahill it reads.

“Headquarters 88th New York Volunteers

Meagher’s Irish Brigade

In Camp near Falmouth, Virginia

January 10th, 1863

Mr. Joseph Cahill

Dear Sir,

I am in receipt of your letter 9th (unreadable). In reply, the painful duty devolves on me of informing you that Thomas Healey of my company was killed in action at Fredericksburg December 13.

A brave and fearless soldier, a sterling, honest man. He died, deeply regretted by his few surviving comrades and by now more so than any.

Your obedient servant,

Jno. C. Foley

1st Lieutenant and Acting Adjutant

P.S.

The poor fellow was buried on the battlefield

Foley participated in the Battle of Chancellorsville before being promoted to Captain and transferred to “F” Company 69th New York State Volunteers in March 1863.[11]

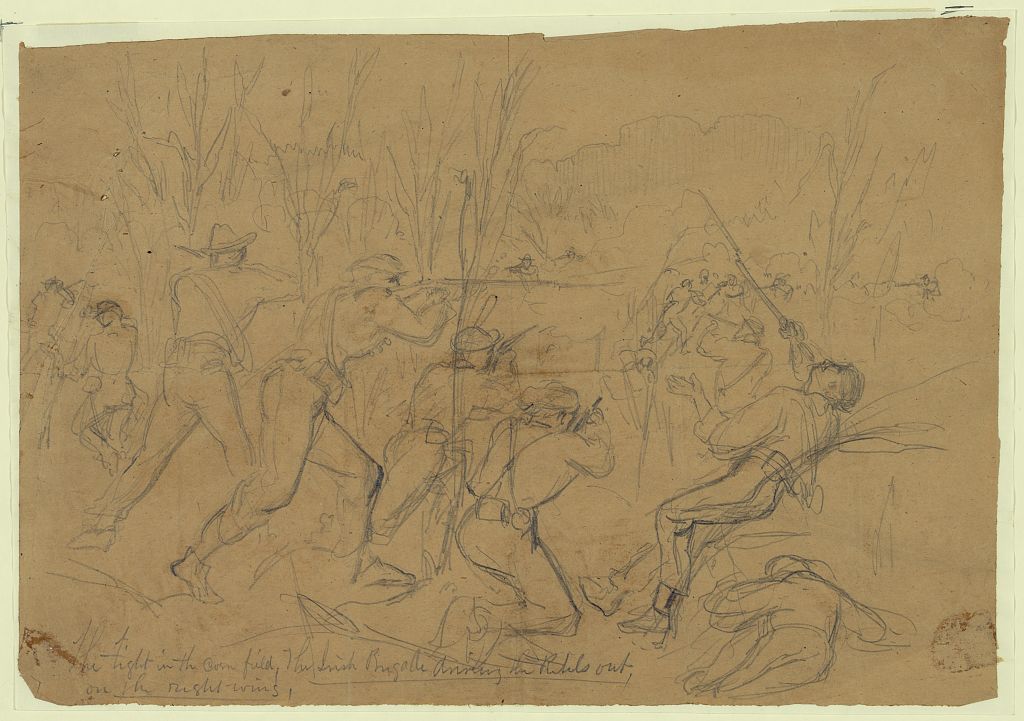

The newly minted Captain Foley would next lead his men into the fray at Gettysburg—the official report of the battle written by Lieut. James J. Smith, 69th New York Infantry states.

“After the line was formed, we moved forward until we met the enemy, who were posted behind

large bowlders of rock, with which the place abounded; but after our line delivered one or two volleys, the enemy were noticed to waver, and upon the advance of our line (firing) the enemy fell back, contesting the ground doggedly. One charge to the front brought us in a lot of prisoners, who were immediately sent to the rear. Our line moved forward (still firing), I should judge, not less than 200 yards, all the time preserving a good line and occupying the most advanced part of the line of battle, when we came suddenly under a very severe fire from the front, most probably another line of battle of the enemy; we also about this time got orders to fall back. We had scarcely got this order when we were attacked by the enemy on our right flank in strong force and extending some distance to the rear, evidently with the intention of surrounding us. It was impossible after falling back to rally the men, as the enemy’s line extended down to the corn-field that we had to cross; also, there was no line immediately in rear of us to rally on; also in consequence of the small number of men in our regiment falling back in double-quick time, and the great confusion that prevailed at the time we crossed the corn-field. I collected about one dozen of our men together and was informed that the division was reforming on the ground that we occupied in the morning. Arriving on the ground where the division was forming, I reported to Colonel Brooke, Fifty-third Pennsylvania Volunteers, then commanding division.”[12]

Captain Foley participated in all subsequent engagements of the 69th, including The Bristoe Campaign and The Mine Run Campaign, where he sustained wounds. He also fought in the battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Cold Harbor, and Appomattox Court House, among others.

He would participate in the famed Grand Review before being mustered out with his company on June 30, 1865, at Alexandria, Virginia.

Captain Foley settled in Brooklyn, where he worked as a clerk. He would meet Mary Julia Morris, whom he married in 1873.[13] A year later, they welcomed a son named William. Foley also became involved in local politics. In February 1904, at sixty-three, he passed away from apoplexy at the Argyle Hotel in Charleston, South Carolina.

The emotional letter written by 1st Lieutenant John C. Foley of the 88th New York Volunteer Infantry is a striking reminder of the personal consequences of conflict and the valor of soldiers like Private John Healey. Foley’s sincere expressions offer insight into the deep sorrow and bonds of friendship that characterized the soldiers’ experiences while emphasizing the lasting effects of such losses on families and communities at home. Foley’s experiences, from battle to his later leadership in various engagements, illustrate the bravery and sacrifices of those who fought in the American Civil War.

[1] “1860 United States Federal Census for John Foley.” Ancestry.Com. January 1, 2009. https://tinyurl.com/2xuwmw39.

[2] “New York, U.S., State Census, 1855 for John Carroll Foley.” Ancestry.Com. January 1, 2013. https://tinyurl.com/36h63j27.

[3] “US, New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900 John Carroll Foley.” Fold3.Com. January 1, 2014. https://www.fold3.com/image/315861092/foley-john-c-page-1-us-new-york-civil-war-muster-roll-abstracts-1861-1900.

[4] “United States Regiments & Batteries New York 88th New York Infantry Regiment.” Civil War In The East. January 1, 2024. https://civilwarintheeast.com/us-regiments-batteries/new-york-regiments-and-batteries/88th-new-york/.

[5] Conyngham, David Power. The Irish Brigade and Its Campaigns: With Some Account of the Corcoran Legion, and Sketches of the Principal Officers. United Kingdom: W. McSorley & Company, 1867. Pg 205-206

[6] “Report of Lieutenant Colonel Patrick Kelly, Eighty-Eighth New York Infantry, of the Battle of Antietam.” Irish in the American Civil War. January 28, 2023. https://irishamericancivilwar.com/after-action-reports/88th-new-york-infantry-regiment/88th-new-york-antietam-17th-september-1862/.

[7] “Thos Healy in the 1860 United States Federal Census.” Ancestry.Com. June 13, 2014. https://tinyurl.com/3tf2bamc.

[8] “US, New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900.” Fold3.Com. February 11, 2014. https://www.fold3.com/image/315719716/healy-thomas-page-1-us-new-york-civil-war-muster-roll-abstracts-1861-1900.

[9] “Report of Colonel Patrick Kelly, Eighty-Eighth New York Infantry.” Irish in the American Civil War. June 13, 2014. https://irishamericancivilwar.com/after-action-reports/88th-new-york-infantry-regiment/88th-new-york-fredericksburg-13th-december-1862/.

[10] Conyngham, David Power. The Irish Brigade and Its Campaigns: With Some Account of the Corcoran Legion, and Sketches of the Principal Officers. United Kingdom: W. McSorley & Company, 1867. Pg 20

[11] “US, New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900.” Fold3.Com. June 16, 2014. https://www.fold3.com/image/315767553/foley-john-c-page-1-us-new-york-civil-war-muster-roll-abstracts-1861-1900.

[12] “US, New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts, 1861-1900.” Gettysburg.Stonesentinels.Com. May 16, 2024. https://gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/union-monuments/new-york/new-york-infantry/irish-brigade/official-report-for-the-69th-new-york/#google_vignette.

[13] “New York, U.S., Marriage Newspaper Extracts, 1801-1880 (Barber Collection).” Ancestry.Com. September 1, 2005. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/8936/records/28266?tid=197293453&pid=312573063909&ssrc=pt.