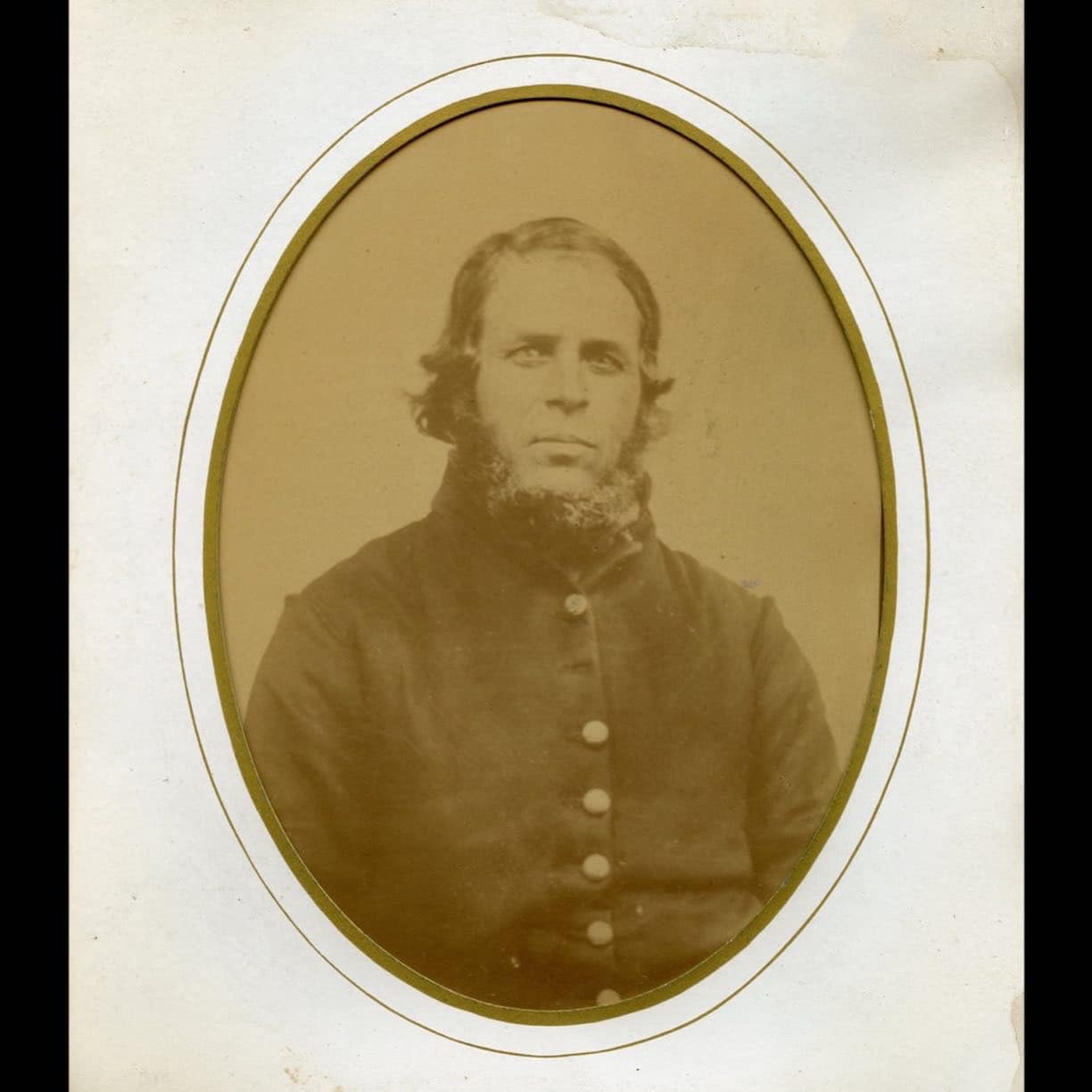

Sometimes one purchases an antique only to discover a fascinating story. This Post-war albumen of Pvt. Augustus H Dayton 14th New York Heavy Artillery, accompanied with letter composed by him is one of those pieces. Augustus Dayton was born in 1817, to Thomas and Almira Dayton in Vermont.[1] Prior to 1850[2] Augustus would marry Catherine Smith, they would have five children.

Before the war Dayton lived in Geneseo and worked as a farmer. In 1862 both of Dayton’s sons enlisted in the 136th NY.[3][4] Augustus would enlist on December 19th, 1863[5], at Genesee New York. He was described on the rolls as being, five feet ten inches tall, with brown hair, blue eyes, and a light complexion. Dayton would be mustered into “L” Co. 14th New York Heavy Artillery as a Private on January 8th, 1864[6].

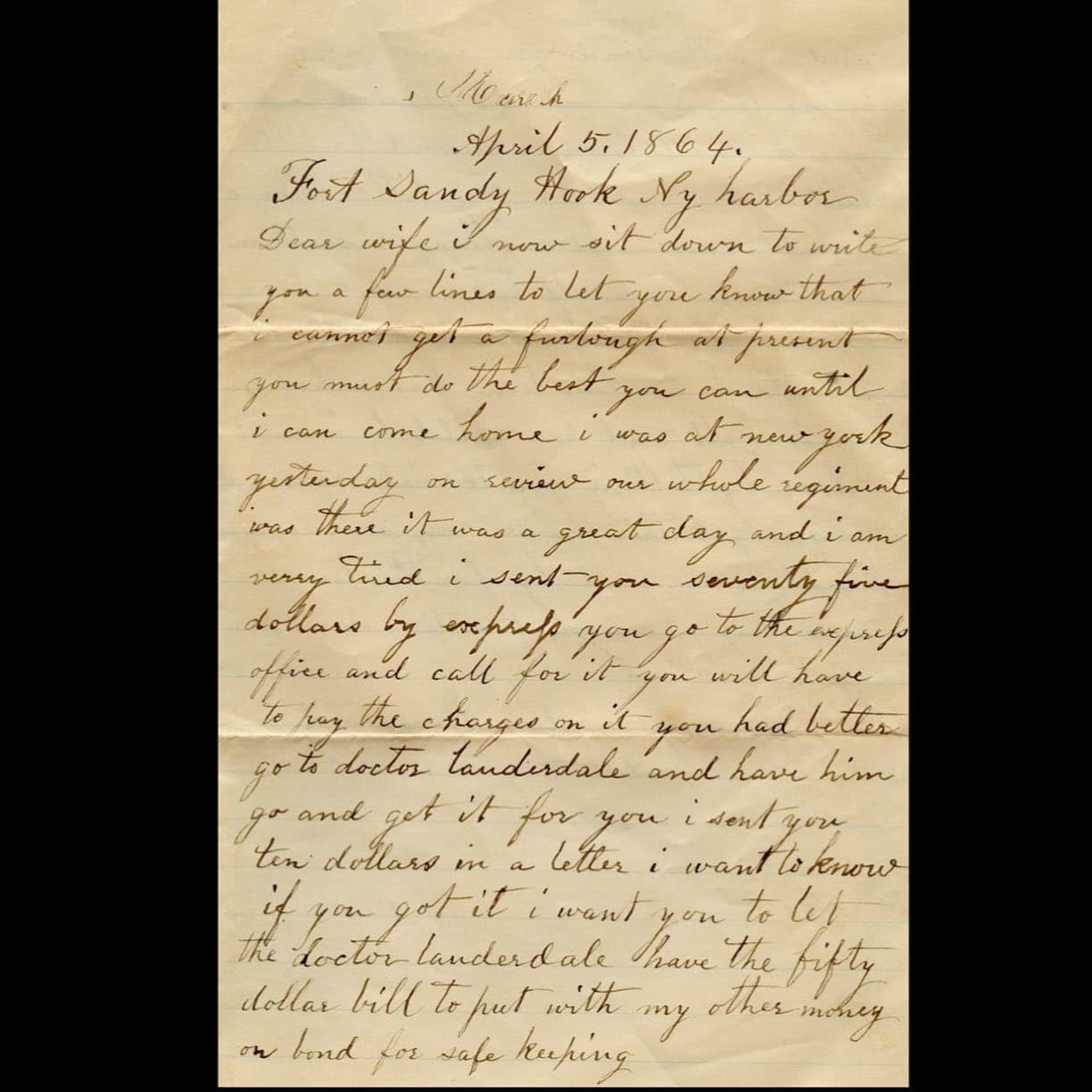

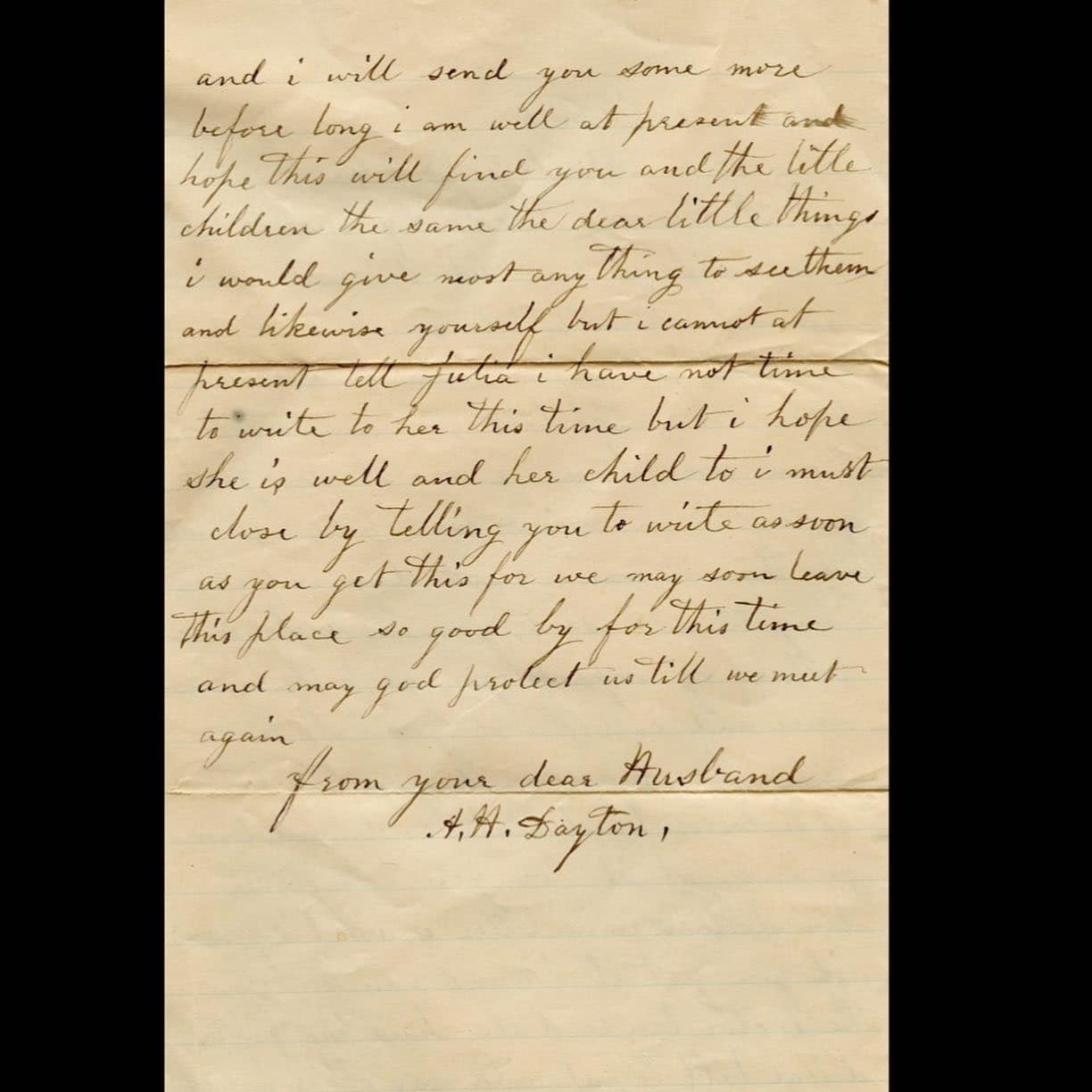

Private Dayton and the 14th N.Y.H.A were sent to New York to defend the harbor. Here is where he would write his wife this letter:

March, April 5, 1864,

Fort Sandy Hook Ny harbor.

Dear wife I now sit down To write you a few lines to let you know that I cannot get a furlough at present you must do the best you can until I can come home I was at New York yesterday on service our whole regiment was there it was a great day and I am very tired I sent you seventy five dollars by express You go to the express office and call for it you will have to pay the charges on it you had better go to doctor lauderdale and have him go and get it for you I sent you ten dollars in a letter I want to know if you got it I want you to let the doctor lauderdale have the fifty dollar bill to put it with my other money on hand for safe keeping and i will send you some more before long i am well at present and hope this will find you and the little children the same the dear little things I would give most anything to see them and likewise yourself but i cannot at present tell Julia i have not time to write to her this time but I hope she is well and her child is to i must i must close by telling you to write as soon as you get this for we may soon leave This place so good by for This Time and may god protect us till we meet again.

From your dear Husband,

A.H. Dayton,

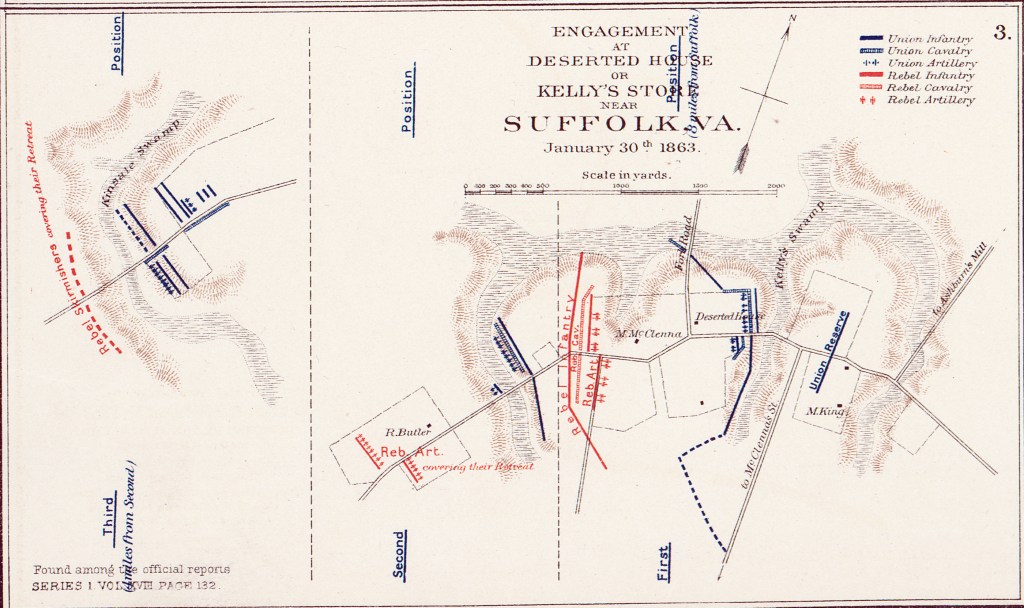

From the forts of New York harbor the 14th was sent south where they were in the following engagements, the Rapidan Campaign, Battle of the Wilderness, Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, The Battle of North Anna, Battle of Totopotomoy Creek, Battle of Cold Harbor, The Siege of Petersburg (including the Mine Explosion), The Battle of the Weldon Railroad, and The Battle of Peebles’s Farm.

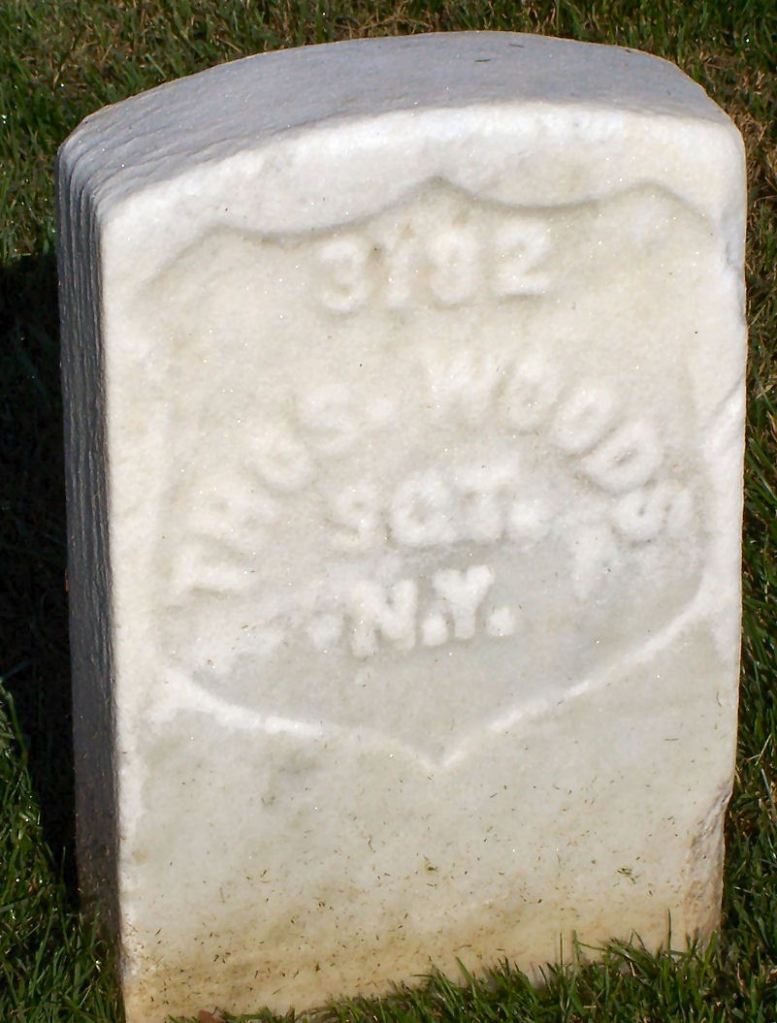

Private Dayton was sent to the hospital at City Point Virginia on October 6th 1864[7] suffering from chronic diarrhea. He would later be sent home on furlough. Private Dayton arrived in Rochester New York on December 15th, 1864.[8] Here he would receive hospital care for his illness. Sadly, Private Dayton would die on March 28th 1865[9]. Dayton’s wife Catherine would apply for a widow’s pension, for her and the two youngest children. Dr. Lauderdale would testify that he attended to Private Dayton, and Dayton also had dropsy as well as insanity before he passed. Dr. Lauderdale would also say that Dayton was a healthy man and a “devoted father”[10].

Catherine would ultimately receive a widow’s pension of eight dollars a month. This would be the equivalent of about one hundred and thirty-seven dollars today.

Let us never forget the sacrifice that Private Dayton made for his country. As well as the loss his family had to suffer in his absence.

[1] “1850 United States Federal Census for Augustus H Dayton New York Livingston Geneseo.” Ancestry®. Accessed January 12, 2022. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/8054/images/4197497-00120?pId=7026585.

[2] Ibid

[3] “Lewis A. Dayton.” American Civil War Research Database. Accessed January 12, 2022. http://civilwardata.com/.

[4] “Henry A. Daton.” American Civil War Research Database. Accessed January 12, 2022. http://www.civilwardata.com/active/index.html.

[5] “New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts Dayton, Augustus H .” Fold3. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.fold3.com/image/316571763.

[6] Ibid

[7] Ibid

[8] “Page 3 Civil War ‘Widows’ Pensions’ Augustus H Dayton.” Fold3. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.fold3.com/image/283724325.

[9] “New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts Dayton, Augustus H .” Fold3. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.fold3.com/image/316571763.

[10] Page 3 Civil War ‘Widows’ Pensions’ Augustus H Dayton.” Fold3. Accessed January 17, 2022. https://www.fold3.com/image/283724325.