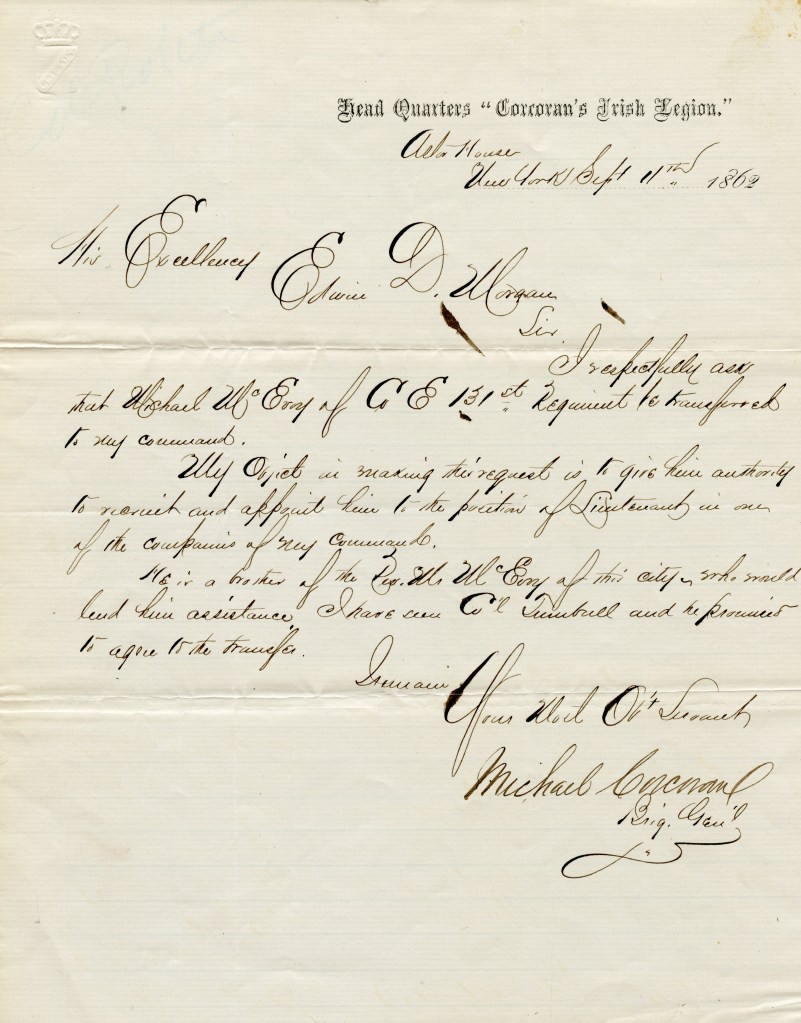

A letter to some is just a piece of paper with words on it. However when one digs deep they can find a hidden story. This letter is written and signed by Brigadier General Michael Corcoran. The letter’s recipient is then Governor of New York Edwin D. Morgan. In this post I am not going to just focus on the “big names” associated with the piece (We can all use Google for that). There is also the interesting tail of Michael McEvoy of Company E, 131st New York. So without further adieu may I present the The letter it reads……

“Sir,

I respectfully ask that Michael McEvoy of Company E, 131st Regiment be transferred to my command.

My object in making this request is to give him authority to recruit and appoint him to the position of Lieutenant in one of the companies of my command.

He is a brother of the Provost Marshal McEvoy of this city, who would lend his assistance. I have seen Colonel Turnbull and he promised to agree to the transfer.

I remain,

Your Most Obedient Servant,

Michael Corcoran

Brigadier General” [1]

Michael McEvoy was born in Ireland around 1828[2]. He was described as five feet nine inches tall, with blue eyes, light hair, and a light complexion.[3] McEvoy would immigrate to America prior to 1850. He was listed on the 1850 United States Federal Census as being a farmer, and married to Cath McEvoy, they had one child James.[4] McEvoy was employed as a Teamster, at the time of his enlistment in the Union army on August 13th, 1862.[5]

. He would be mustered into “E” Co 131st infantry as a private on September 6th.[6] Per General Corcoran’s request McEvoy would be transferred to “D” Co. 170th New York on September 19th, 1862.[7] He would be mustered in as a private on October 7th, 1862. Private McEvoy would participate in the battle of Deserted House. He would later be granted leave on March 21st, 1863, McEvoy would never return to service[8]. Private McEvoy would be listed as a deserter from camp at Suffolk Virginia on April 3rd, 1863.[9] That is where his trail ends for now.

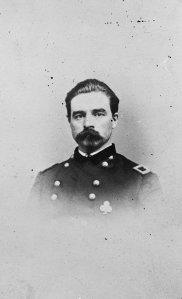

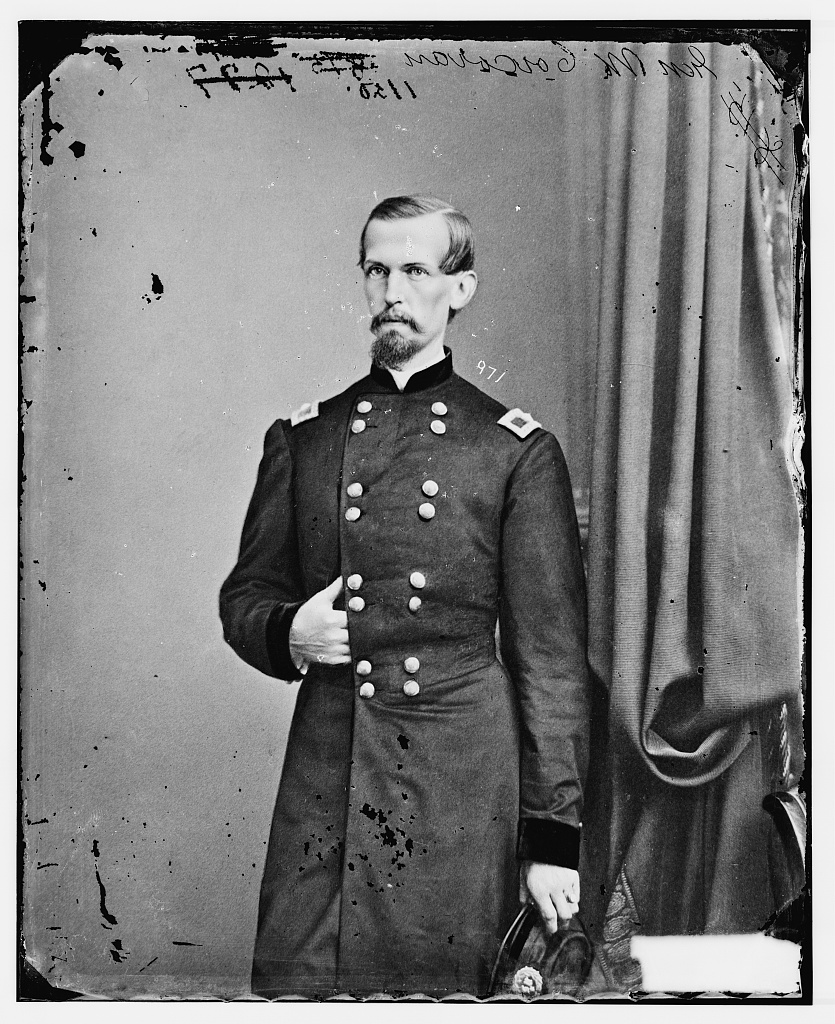

Michael Corcoran was born in Carrowkeel, county Sligo Ireland. He was a member of the Irish Nationalist Guerrilla force known as the Ribbonman. His ties to this group were eventually discovered in 1849, so he immigrated to New York City in order to avoid capture.[10] To gain a position in society Corcoran joined the 69th New York State Militia as a private. He would advance rapidly due to, “his military passion and his previous knowledge of military tactics were a great advantage to him.”[11] Corcoran moved up in rank and became a Colonel. It was in this capacity that Corcoran became a hero to the Irish Nationalist, as well as the overall Irish immigrant population of New York. When he chose not to parade the 69th in front of the Prince of Whales upon the Princes visit, saying that “as an Irishman he could not consistently parade Irish-born citizens in honor of the son of a sovereign, under whose rule Ireland was left a desert and her best sons exiled or banished.”[12] His action resulted in a court-martial. However, it was overturned due to the need of good officers to fight in the Civil War.

General Michael Corcoran, U.S.A. United States, None. [Between 1860 and 1865] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018667330/.

Corcoran resumed his rank in the 69th New York and was present at that Battle of First Manassas, where he was captured. Corcoran spoke of this later by saying, “I did not surrender until I found myself after having successfully taken my regiment off the field, left with only seven men and surrounded by the enemy.”[13] Corcoran was eventually exchanged over a year later, and was received back with acclaim. He was given the rank of Brigadier General and put in command of his own troops, known as Corcoran’s “Irish Legion.” The first battle of the Legion took place during the Battle of Deserted House Virginia. Although not one of the biggest battles of the war, Corcoran demonstrated calmness under fire and his men showed how they admired Corcoran by following his every commanded under intense battle conditions. Sadly this would be Corcoran’s last major battle as he was killed later that year when he fell from his horse. Even though Corcoran’s life was cut short his legend and the Prince of Wales incident continued to inspire men, especially those of his Legion who were fighting for their adopted homes as well as Irish pride.

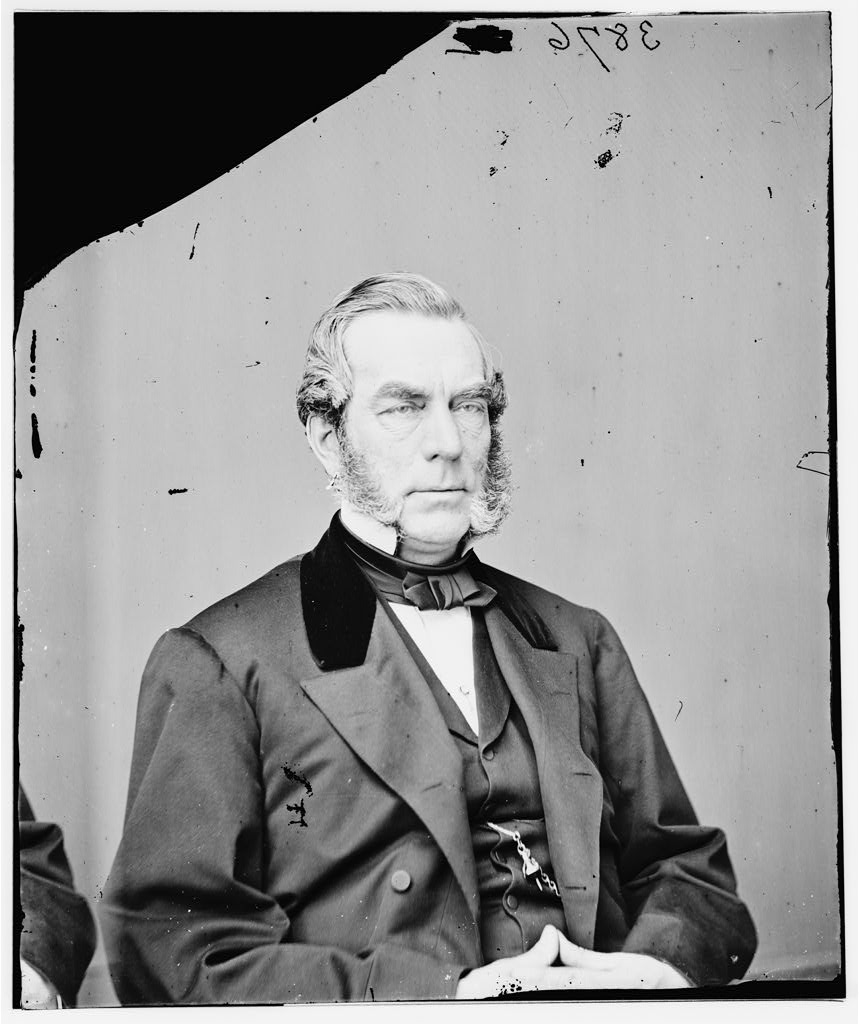

The National Governors Association has written this about Gov. Edwin D. Morgan.

“EDWIN D. MORGAN, the twenty-third governor of New York, was born in Washington, Massachusetts on February 8, 1811. His education was attained at the Bacon Academy in Colchester, Connecticut, where his family moved to in 1822. Morgan established a successful business career, with holdings in the banking and brokerage industries. He first entered politics in Connecticut, serving as a member of the Hartford city council, a position he held in 1832. After moving to New York, he served as alderman of New York City in 1849; was a member of the New York State Senate from 1850 to 1851; and served as the state immigration commissioner from 1855 to 1858. He also chaired the Republican National Committee from 1856 to 1864. Morgan next secured the Republican gubernatorial nomination, and was elected governor by a popular vote on November 2, 1858.

. United States, None. [Between 1860 and 1870] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2018669639/.

He was reelected to a second term in 1860. During his tenure, the state’s canal system was advanced; Vassar College was founded; and volunteers were raised and equipped for service in the Civil War. Morgan also served as major general of volunteers during the war, as well as serving as the commander for the Department of New York. After leaving the governorship, Morgan was elected to the U.S. Senate, an office he held from 1863 to 1869. From 1872 to 1876 he chaired the Republican National Committee; and in 1881 he turned down an appointment to serve as U.S. secretary of treasury. Governor Edwin D. Morgan passed away on February 14, 1883, and was buried in the Cedar Hill Cemetery in Hartford, Connecticut.” [14]

Although these three men are from completely different backgrounds, their stories intersect in this one document. Historical stories are everywhere, you just need to dig under the surface to find them.

[1] Corcoran, Michael. Letter to Gov. Edwin D, Morgan. “Brigadier General Michael Corcoran Request For Michael McEvoy.” New York, New York: Astor House, September 11, 1862.

[2] “Page 1 New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts McEvoy, Michael.” Fold3. Accessed December 31, 2022. https://www.fold3.com/image/315981459.

[3] Ibid

[4] “Michael McEvoy in the 1850 United States Federal Census.” Ancestry. Accessed December 31, 2022. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/7008512:8054?tid=&pid=&queryId=6a9bb6ca9453a20b805c27f011dfac83&_phsrc=csG312&_phstart=successSource.

[5] Page 1 New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts McEvoy, Michael.” Fold3. Accessed December 31, 2022. https://www.fold3.com/image/315981459

[6] Ibid

[7] “Page 1 New York Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts Michael McEvoy.” Fold3. Accessed December 31, 2022. https://www.fold3.com/image/316135643.

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid

[10] Pritchard, Russ A. The Irish Brigade : a Pictorial History of the Famed Civil War Fighters. (Philadelphia,

[11] Conyngham, The Irish Brigade and It’s Campaigns , 537

[12] Ibid

[13] Ibid, 538

[13] Shiels, Damian. Irish in the American Civil War Exploring Irish involvement in the American Civil War . March 18, 2012. http://irishamericancivilwar.com/2012/03/18/baptism-of-fire-the-corcoran-legion-at-deserted-house-virginia-30th-january-1863/ (accessed 11 20, 2013).

[14] Sobel, Robert, and John Raimo. “Edwin Denison Morgan.” National Governors Association. Accessed November 3, 2023. https://www.nga.org/governor/edwin-denison-morgan/.