In the mid-nineteenth Ireland was under oppressive English rule and suffering from famine. Many young Irish men fled their homeland to America in quest of a better life only to end up in the middle of a bloody civil war. This war divided bold Irishman against one another and created American heroes out of these foreign born sons. The Irish fought in almost every major engagement of the American Civil War. It is estimated that one hundred and fifty thousand Irishmen fought in this struggle and a high percentage of those men never returned. (1) They were left as Irish Brigade Captain David Power Conyngham put it, “On the bloody fields of Virginia, down amid the cotton fields of Georgia and in the swamps of the Carolinas, lie the bleached bones of many an Irish Soldier and chief.” (2) After the war General Robert E. Lee spoke about Irish soldiers by saying, “The Irish soldier,’ he said, ‘fights not so much for lucre as through the reckless love of adventure, and, moreover, with a chivalrous devotion to the cause he espouses for the time being.” (3) After reading these quotes, one can raise the question why is this so?

This four part series will show it was due to the very fact that they were Irishmen whom possessed a unique background, making them predisposed to greatness in battle. In essence there are four driving forces that will explain why the Irish fought with great success during the American Civil War. These driving forces are: religion, acceptance, Irish Nationalism and the Irish culture. This week we will focus on how religion influenced the Irish in battle?

Religion in Ireland was a fundamental way of life. It permeated not only their daily lives, but also their politics. Philosopher and politician Gustave De Beaument observes, “Ireland was eminent for its piety and sanctity amongst the most Christian nations. Its priests were the head of political as well as religious society. In this country, where the social powers were feeble, uncertain and ill-defined there was no fixed and invariable rule but that of religion no undisputed authority except priests.” (4) Although Beaument was speaking of the late 16th century one can easily speculate how this tradition would be an essential part of Irish culture in the 19th century. At the outbreak of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln thought that spiritual guidance would be important for the Union soldiers. However, he overestimated the soldiers acceptance of the clergy in there regiments. Out of seven hundred Union regiments mustered, almost half decided to “find their way to hell without the assistance of clergy.”(5) The Irish in the Union regiments were mostly Catholic and did not think like the average Union soldier. They voted to have priests accompany their units, as religion was an important foundation of Irish culture. They knew battlefield motivation and encouragement is an important part of any conflict and can be the difference between victory and defeat. Having priests accompany them would help increase everyday moral, thus boosting the fighting spirit within them.

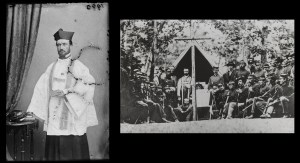

Photo shows: (back row) Patrick Dillon, unidentified; and (front row, left to right) unidentified, James Dillon, and William Corby. The identified men are priests of the Congregation of the Holy Cross, University of Notre Dame. (Source: E. Hogan, Univ. Notre Dame Archives, 2009.) Photograph from the main eastern theater of war, the Peninsular Campaign, May-August 1862.

In order to heed this call for priests by the Irish fighting for the Union, Father Edwin Sorin, then president of the University of Notre Dame, ordered that Notre Dame was to at once deliver these Catholic soldiers the support they needed in order to offer the “help of their holy religion.” (6) Amongst those sent were Father William Corby and Father James Dillon. Father Corby was a second generation Irishman, born in Detroit in 1833, and Chaplin of the 88th New York. Father Dillon was Irish born and the Chaplin of the 63rd New York. Both regiments were part of the legendary Irish Brigade. Both of these men, along with many other priests in Irish regiments of the Union, helped drive the success of the Irish and in more than one documented case may have shifted the tide of battle. One battle where the Irish’s devotion to religion can be seen is during the battle of Antietam. Father Corby road his horse ahead of the 88th New York’s line, offering them a “hasty absolution.” (7) The Father then rode into the fray and heard confessions during the thick of the fighting. The idea of absolution before God was extremely important to these Irish-Catholic soldiers, as they believed that they “can be restored to grace by confession and the sacrament of penance.” (8)

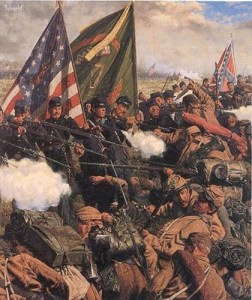

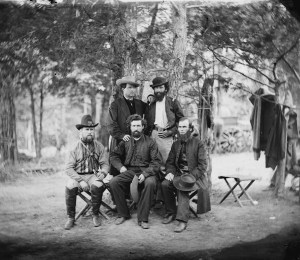

Sons Of Erin by Don Troiani this work depicts Father Corby giving absolution in front of the 88th New York during the Battle of Antietam on horseback

One can see how this could help calm the nerves of these men and help motivate them in the battle. Furthermore, after the battle Union General George McClellan said, “The Irish Brigade sustained their well-earned reputation, suffering terribly in officers and men, and strewing the ground with their enemies, as they drove them back.” (9) Perhaps the most famous example of religious motivation by a chaplain took place at Gettysburg. On the second day of battle Father Corby stood upon a rock and offered a general absolution to the men of the Irish Brigade. He ended his blessing with the words, “The Catholic Church refuses Christian burial to the soldier who turns his back upon his foe or deserts his flag.”(10) These words inspired the men to fight with all they had, and the fighting was fierce. Captain Conyngham described the fighting in the following passage, “Our rifled guns repelled with effect and for two hours the air seemed literally filled with screaming messengers of death.” (11) Peter Welsh was the Color Sergeant of the 28th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers, a unit that was part of the famed Irish Brigade. He wrote this about the battle, “it was a hot place our little brigade fought like heroes and we drove the enemy nearly a quarter of a mile.” (12) The Irish Brigade came into that battle with five hundred and thirty men and left with three hundred of the original recruitment of over two thousand. (13) Eventually, the Confederate troops did push the Irish Brigade back a little during the struggle for what was later known as the Bloody Wheatfield. By the end of the battle of Gettysburg, the Union had defeated the Confederates and the Irish Brigade played a valuable role in this victory. One can easily make the connection that father Corby’s words helped and proved to be an inspiration to the men as they faced a tough enemy.

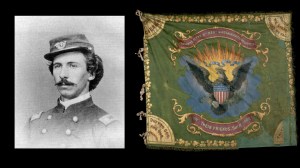

Absolution Under Fire, by Paul Wood this work shows Fr. Corby giving a general absolution to the Irish Brigade before the Battle of Gettysburg. The painting was done in 1891 , while Wood was a Notre Dame student.

Chaplains earned great respect amongst their regiments, which strengthened the effect they had on Irish soldiers; “Chaplin’s, like officers, won the respect with their bravery under fire. In the male time preserve of a wartime, army courage is currency with which men’s hearts are purchased.”(14) Father Dillon was one of the members of the cloth that was very influential amongst his regiment. The respect that he earned can be seen during the battle of Malvern Hill. When the 63rd New York was under heavy fire the men were unsure of their officers because they were inexperienced. The men were claiming that they were father Dillon’s regiment and shouted, “Yes, yes! Give us Father Dillon.” (15) Father Dillon stepped up into the skirmish and told the men to have confidence in their officers and restored order back in the ranks. Union General Fitz John Porter wrote of the Irish Brigades actions that day saying, “I found that our force had successfully driven back their assailants. About fifty yards in front of us, a large force of the enemy suddenly arose and opened fire with fearful volleys upon or advancing line. I turned to the brigade….and found it standing like a stone wall and returning a fire more destructive than it received.” (16) A feat that would have been nearly impossible if Father Dillon did not organize the disorderly rabble of his regiment earlier in the fight.

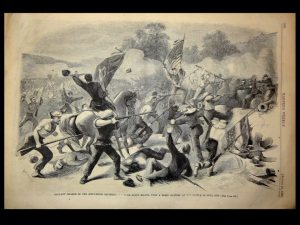

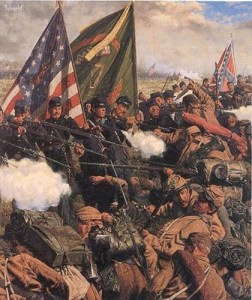

Painting titled A Donnybrook At Dusk By Bradley Schmehl, depicting the Irish Brigade at Malvern Hill

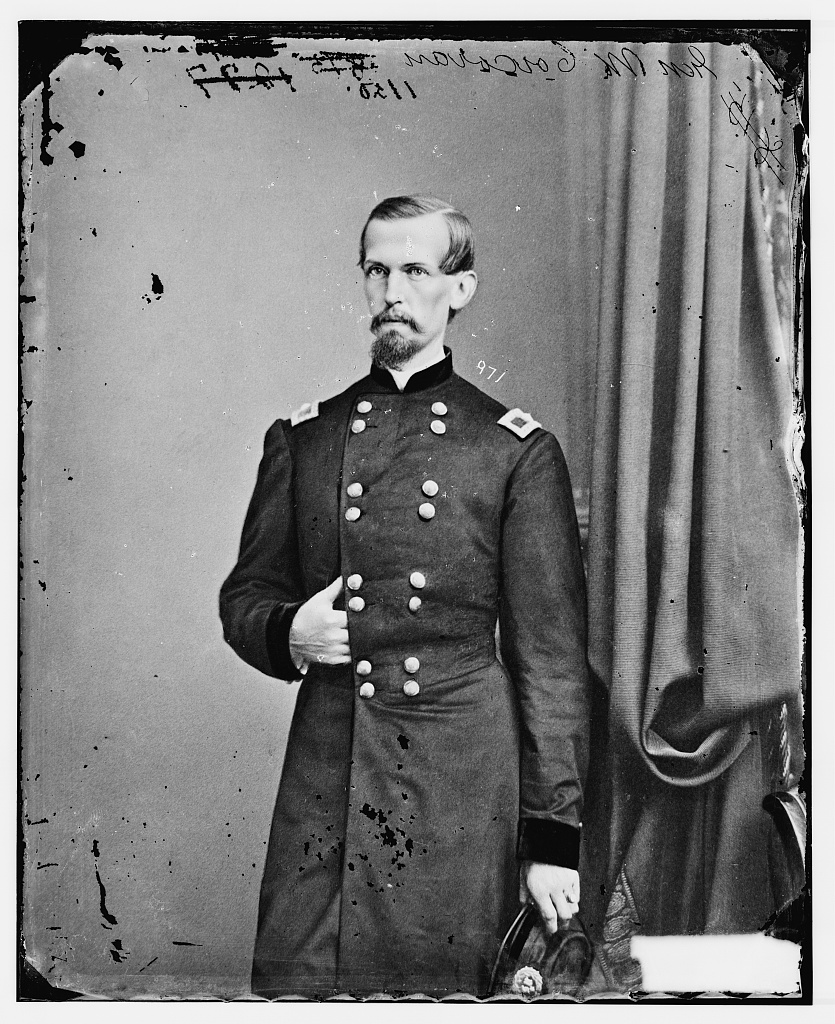

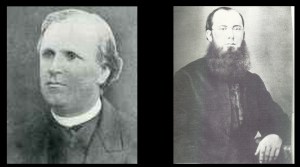

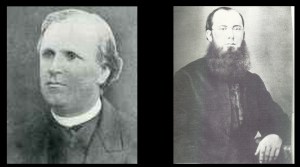

Catholic chaplains were not just a staple in Union Irish regiments, as they were also highly regarded in Confederate regiments. One such priest was Father Matthew O’Keefe, who was the chaplain of William Mahone’s Brigade of Virginians. He earned the respect of his followers due to the fact that he drew two pistols on a would be assassin, thus thwarting his plot. (17) Father O’Keefe also volunteered for service to the cause even after being denied by his bishop. (18) One can imagine that due to this esteem O’Keefe’s words and leadership would have a positive effect on the men he tended to and once again show what a driving force religion was in making the Irish soldiers of the Civil War such fierce fighters. Perhaps the most influential Irish priest of the Confederacy was Father John Bannon. He was Irish born and the priest of the Missouri Brigade. He was present during the Siege of Vicksburg and offered Catholic services, as well as administered food and water. He also gave last rights heard confessions and tended to the wounded. This would have had a profound effect on the moral of the men and although the city eventually fell to the Union, the care he provided would add time to the siege and help Confederate forces leave the city to fight another day. It was due to the respect he earned during this, as well as his staunch support of the Confederacy, that Father Bannon was sent in the dark of night to become a foreign ambassador to Ireland. (19)

Left: Father Matthew O’Keefe, Right: Father John Bannon

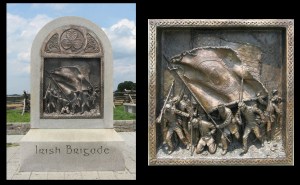

Chaplains were not the only way Confederate Irish were motivated by religion in battle. This can be demonstrated by the fact that the Colors of the South Carolina Irish Volunteers were presented by Bishop Patrick Lynch during a Catholic mass. Bishop Lynch spoke to the men saying, “Receive it then {the flag} rally around it. Let it teach you of God, of Erin, of Carolina. Let it teach you your duty on this life as soldiers and Christians, so that fighting the good fight as Christians, you may receive the reward of eternal victory from the King of Kings.” (20) By doing this Bishop Lynch in essence consecrated the colors. By making the colors sacred he made them significantly meaningful to those of the Catholic faith. This would then provide additional inspiration to the men in battle. These Irish Confederates knew that if they were to die while fighting it would be for a virtuous cause and under a flag blessed by God.

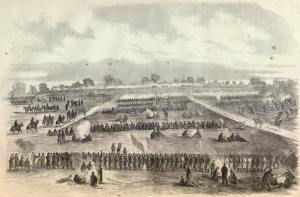

Not only did the clergy of both sides offer battlefield motivation to the Irish fighting in the war, but they also helped care for the soldier’s physical and mental health off the frontline. Supporting them behind the scenes as well was just another way to boost their moral. Military historian Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Baynes speaks of the importance of soldier’s morale in his work Morale – A Study of Men and Courage. He stated: “High morale is the most important quality of a soldier. It is a quality of mind and spirit which combines courage, self-discipline, and endurance. It springs from infinitely varying and sometimes contradictory sources, but is easily recognizable, having as its hall-marks cheerfulness and unselfishness. In time of peace good morale is developed by sound training and the fostering of esprit de corps. In time of war it manifests itself in the soldier’s absolute determination to do his duty to the best of his ability in any circumstances. At its highest peak it is seen as an individual’s readiness to accept his fate willingly even to the point of death, and to refuse all roads that lead to safety at the price of conscience.” (21) Positive morale of the soldiers was significant to the men of the Irish Brigade during the Seven Days Battle. The men suffered long forced marches at night and hard fighting during the day, which would be enough to break any soldier. However, the men of the Brigade had support from their clergy. Around the clock priests heard confession and offered words of encouragement to the men keeping their spirits up. (22) The effects of which can be seen at the Battle of Savage Station, which was the fourth battle of the Seven Days Campaign. The Confederate attack at Savage Station was swift and organized. Non-Irish Union regiments had a hard time staying strong. For instance, the 106th Pennsylvania “broke and then fled in panic after losing one hundred men in killed and wounded.” (23) However, the Irish Brigade “greatly distinguished themselves, charging in some cases up to the very cannon of the enemy. One of the Rebel guns they hauled off, spiked the guns, demolished the carriages, and then abandoned them.” (24) The juxtaposition of these two units in the same battle goes to show the effect that the Chaplains had on their flock, and how that morale boost translated into action.

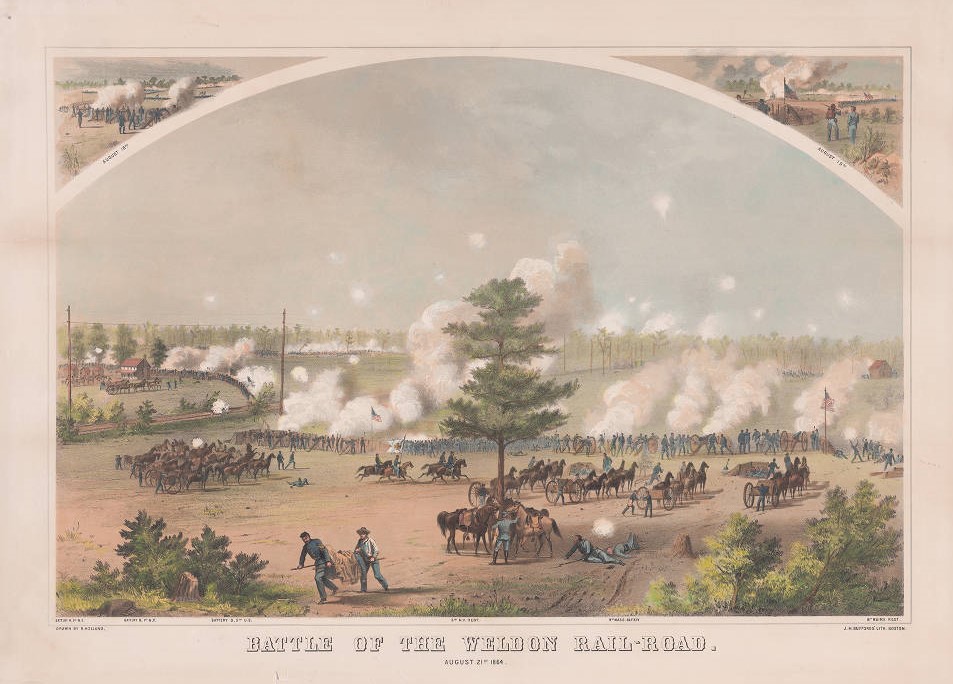

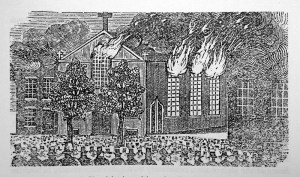

Engraving from the July 26th 1862 edition of Harper’s Weekly depicting the Battle of Savage Station.

Religious services were yet another way to boost the morale of the men in the war, and this fact was not lost on the commanding officers of Irish regiments. The 9th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, also known as Boston’s Irish Ninth, lost their chaplain, Father Thomas Scully, for quite some time due to illness. During this time the commanding officer, Colonel Patrick R. Guiney, of the 9th Massachusetts borrowed the services of Father Corby. Both men met with General Charles Griffin, commander of the First Division of the Fifth Army Corps, to see if Father Corby could take on the 9th Massachusetts in addition to the 88th New York. Griffin knew that most of his men were of the Catholic denomination, and was surprised that they would be without a Catholic priest. General Griffin then suspended drill for a week so that his men could attend to “their religious duties.” (25) One can easily infer from this decision that General Griffin could see the value on religion and the effect it had on soldiers in battle. Furthermore, he realized the importance of how to use clergy to motivate the Irish in his ranks.

Left: Father Thomas Scully Right: Father Scully prepares to say mass to Bostons Irish 9th at Camp Cass, Arlington Heights, Virginia.

Religion can be a powerful motivator and help an army. Father Corby himself writes of this by saying, “The feature in any army is indeed, no small matter… Men who are demoralized and men whose consciences trouble them make poor soldiers. Moral men, men who are free from the lower and degrading passions make brave, faithful and trustworthy soldiers.”(26) By embracing their religion during the war the Irish had a driving force that most other soldiers of the war did not. This force helped push them to do great things in battle; and the idea of the Irish being “brave, faithful and trustworthy soldiers” can be seen throughout the American Civil War.

Notes;

1) Donald, Robert Bruce. Manhood and Patriotic Awakening in the American Civil War: The John E. Mattoon Letters, 1859-1866. (Lanham, Maryland:Hamilton Books. 2008) 17

2) Conyngham, David Power. The Irish Brigade and Its Campaigns. (New York: Fordham University Press, 1994.) 8

3) Cavanagh, Michael. Memoirs of Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher : comprising the leading events of his career chronologically arranged, with selections from his speeches, lectures and miscellaneous writings, including personal reminiscences. (Worcester, Mass: The Messenger Press, 1892.) 470

4) De Beaumont, Gustave. Ireland Social, Political, and Religious . (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press Of Harvard University Press , 2006.) 10

5) Schmidt, James M. Notre Dame and the Civil War : Marching Onward to Victory. (Charleston, SC: History Press, 2010.) 30

6) Ibid

7) Corby, William. Memoirs of Chaplain Life : Three Years with the Irish Brigade in the Army of the Potomac. (New York: Fordham University Press, 1992.) 112

8) Campbell, Ted. 1996. Christian Confessions : a Historical Introduction. 1st ed. (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press.) 96

9) Corby, Memoirs of Chaplain Life, 373

10) Mulholland, St. The Story of the 116th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers in the War of the Rebellion. (New York: Fordham University Press, 1996.) 407

11) Conyngham ,The Irish Brigade and It’s Campaigns, 416-417

12) Welsh, Peter. 1986. Irish Green and Union Blue : the Civil War Letters of Peter Welsh, Color Sergeant, 28th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers. (New York: Fordham University Press 1986.) 109

13) Wright Steven J., The Irish Brigade (Springfield, PA: Steven Wright Publishing, 1992.) 23

14) Corby, Memoirs of Chaplain Life, XVI

15) Schmidt, Notre Dame and the Civil War, 34

16) Corby, Memoirs of Chaplain Life, 370

17) O’Brian, Sean, The Irish Americans In the Confederate Army. (McFarland & Co, 2007) 40

18) Unknown. New York Times. January 29, 1906. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=FB0F16FA3B5A12738DDDA00A94D9405B868CF1D3 (accessed September 10, 2014).

19) Gleeson, David. The Green and the Gray: The Irish in the Confederate States of America. (The University of North Carolina Press, 2013.) 169-170

20) Ibid, 150

21) Baynes, John Morale: A Study of Men and Courage, (Garden City Park, NY: Avery Publishing Group, 1988.) 108

22) Corby, Memoirs of Chaplain Life, 87

23) Smucker, Samuel M. A History of the Civil War in the United States : with a Preliminary View of Its Causes, and Biographical Sketches of Its Heroes. (Philadelphia: J.W. Bradley, 1865.) 289

24) Ibid

25) Corby, Memoirs of Chaplain Life, 315

26) Ibid. 271