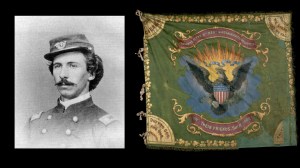

Brigadier General Billy Mitchell, United States Army Air Service

Brigadier General William “Billy” Mitchell was a born leader and a military visionary. He made numerous contributions to the United States and its use of air power. Even though his career ended in disgrace, Brigadier General Billy Mitchell’s ideas were ahead of his time. Mitchell personally saw the power of the air force in World War I. Stating, in 1918, “The day has passed when armies on the ground or navies on the sea can be the arbiter of a nation’s destiny in war. The main power of defense and the power of initiative against an enemy has passed to the air.” (1) Mitchell would spend the rest of his military career trying to prove this statement true by conducting tests and writing theory’s that are still used to this day.

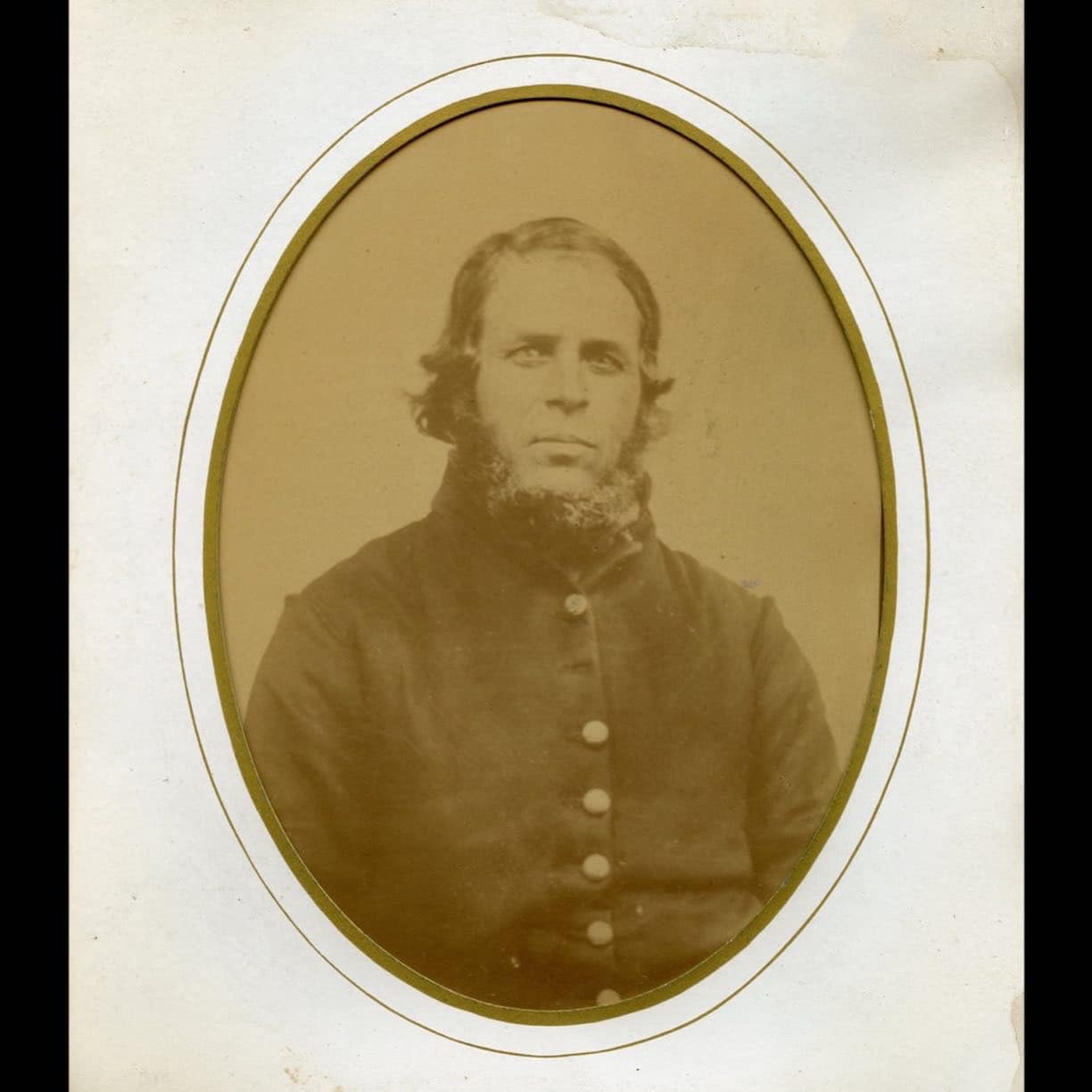

William “Billy “Mitchell was born December 29th 1879 into a family of wealth and privilege. This gave him the advantage of a good education, as well as giving him opportunities not afforded to the average individual. These opportunities included travel. As a child, Mitchell’s father, 1st lieutenant John L. Mitchell who fought with the 24th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War, would take young Billy to Waterloo and other battle sites around the world. There Billy was told of the gallant deeds and heroism that took place at these battle sites. Mitchell’s sister Ruth stated, “Willie could see the old battles going on as if they were unfolding before his eyes.” (2) In 1898 the United States was on the verge of conflict in Cuba. It was at this time, based on his background, that a youthful Billy Mitchell would sign up for service seeking adventure, thus beginning his twenty-eight year military career.

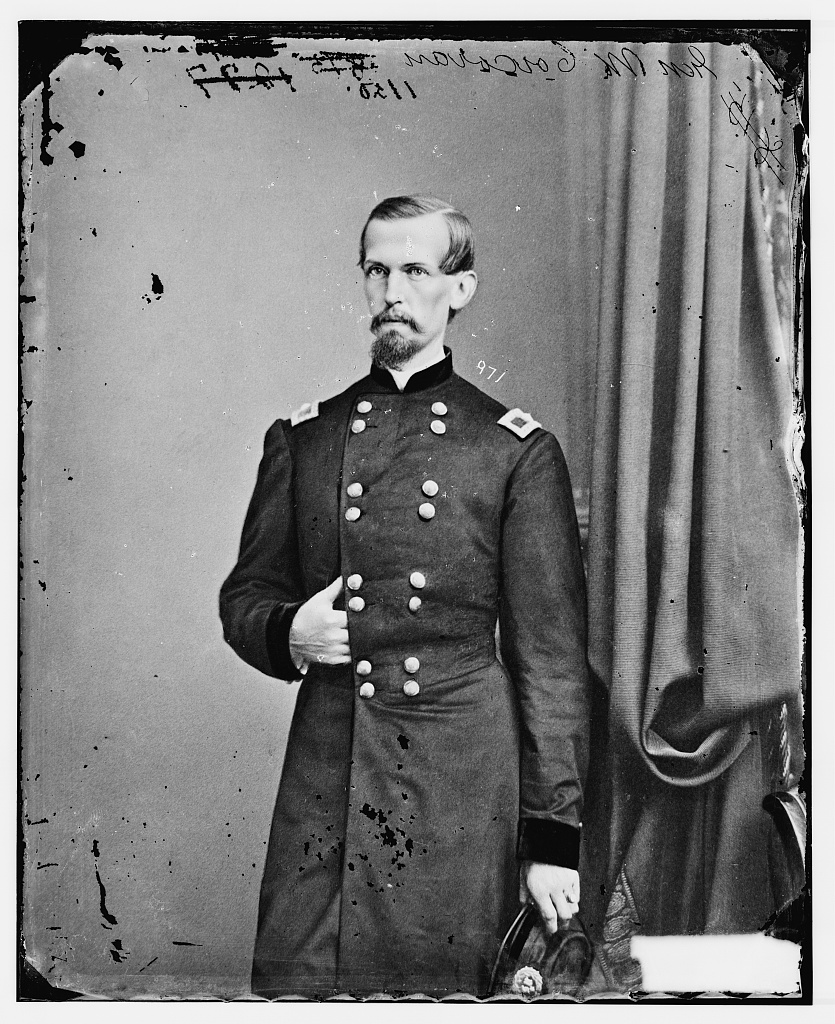

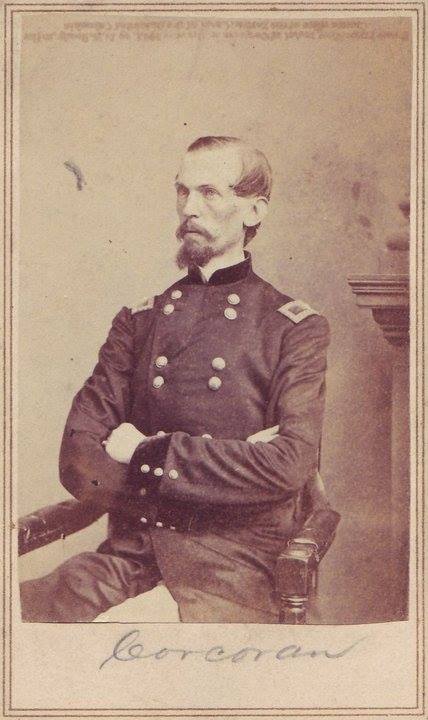

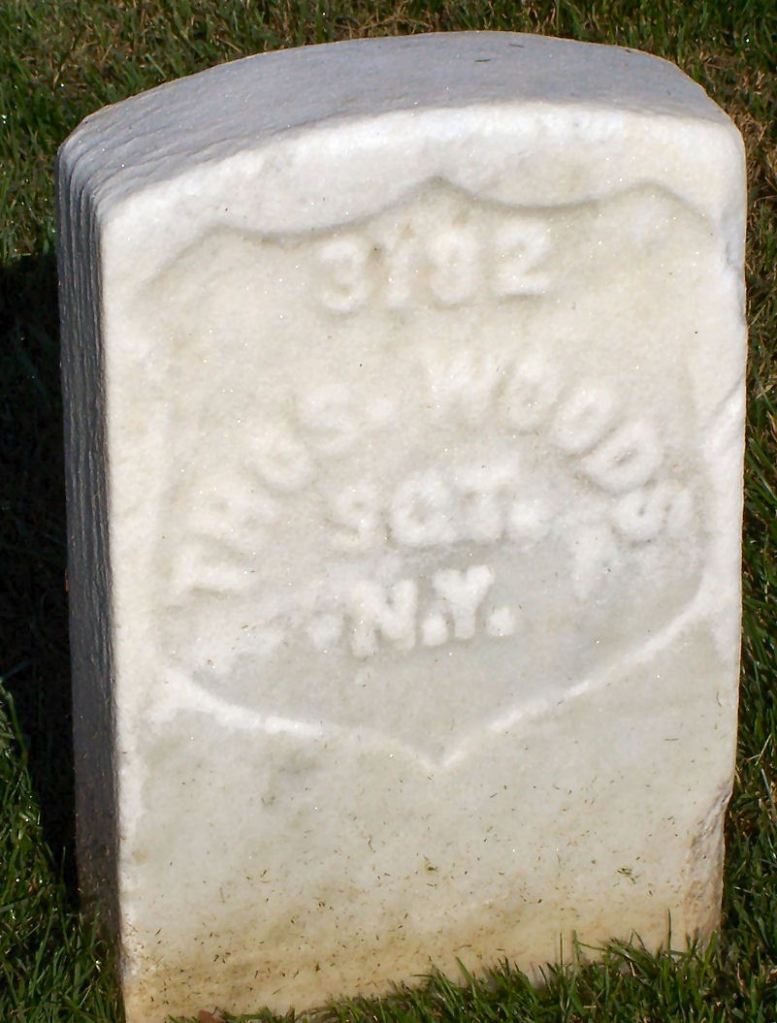

Billie Mitchell’s Father John L. Mitchel

Mitchell was sent to Florida with the First Wisconsin Volunteers. Within a week he made the rank of Second Lieutenant, becoming the youngest officer in service at just eighteen years of age. (3) During this campaign, Mitchell did not see any action. This frustrated him, he remarked to his father, “Here I have been since the war without any foreign service to speak of and have not been in any engagements as of yet. How would you have felt in the Civil War if you had been out of the way somewhere?” (4) In 1899 there was an insurrection in the Philippines and on November 1st of that year, Mitchell arrived there under the command of General Arthur Macarthur to help put down the insurgency. This would give Billy his wish to see combat and he did so as a member of the Signal Corps. It was the job of the Signal Corps to travel with the infantry and sometimes ahead of them to lay down wires to establish telegraph communications. This put Mitchell in the thick of the fighting. He related one particularly dangerous operation in Mabalang to his sister Ruth saying, “I got our line into the rebel trenches ahead of the troops. The insurrectionists ran, blowing up a big railroad bridge. We had a pretty good scrap there. As they retreated along the railroad track they were not more 300 yards away from us in columns of fours; but there was not a single company of our troops insight of them. I thought I could bring somebody down with my pistol, they looked so near, but I had to use my carbine.” (5) By the end of the Philippine insurrection Mitchell’s signalmen had broken up several rebel bands and captured seventy insurgent flags, furthermore Mitchell was promoted to the rank of Captain for his efforts. (6)

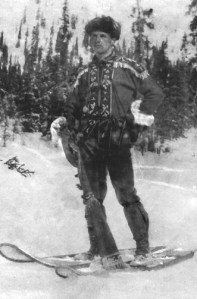

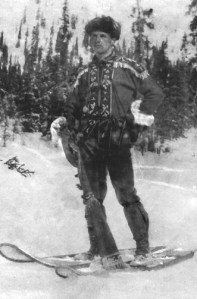

Mitchell in Alaska with the Signal Corps

Mitchell decided to make the Army his career and spent time in Alaska with the Signal Corps engineering communications between isolated outposts and the United States as well as Canada, again with much success. After this he was assigned to Fort Leavenworth known back then as the “intellectual center of the army.” (7) It was there in 1906 that Mitchell first discovered the importance that the air would play in future warfare. He introduced his findings in a presentation given to the Signal Corps School entitled “The Signal Corps with Divisional Cavalry and Notes on Wireless Telegraphy, Searchlights and Military Ballooning.” (8) In this presentation, Mitchell spoke of dirigibles saying they may “Cruise at will over a battlefield, carrying messages out of a besieged fortress or sail alone above a beleaguered place, immune from the action of men on the earth’s surface.” (9) In the same article, Mitchell went on to say, “By towing another balloon, loaded with explosives, several hundred pounds of guncotton could be dropped from the balloon which it is towing in the midst of an enemy’s fortifications.” (10) These ideas were groundbreaking. As the awareness in the use of air combat was in its infancy, Mitchell saw its potential by concluding his work with this statement. “Conflicts, no doubt, will be carried on in the future in the air” (11)

Mitchell took a staff position in Washington DC where he stayed in till 1916 when due to his frustration at the lack of promotion and a desire to see field service he joined the Armies Aviation Squadron. In this capacity, Mitchell was promoted to Major and assigned to bolster military aviation training. He took part in the training getting fifteen hours of flight time while taking thirty-six flights. (12) Although Mitchell did not earn his wings with this training, he was considered one of America’s top aviation experts. It was due to this fact that on March 19th 1917 then Lieutenant Colonel Mitchell was sent to France as an aeronautical observer. By the time he arrived, the United States had declared war on Germany beginning American involvement in the First World War.

While Mitchell was in France, he was amazed to see the advancements the French had made in military aircraft. He remarked, “I had been able to flounder around with the animated kites that we called airplanes in the United States, but when I laid my hand to the greyhounds of the air they had in Europe, which went twice as fast as ours, it was an entirely different matter.” (13) It was this experience that started to display to Mitchell the full potential of modern air power. He immediately petitioned the United States Army to manufacture or purchase these new advanced aircraft, but he was rebuffed on multiple occasions making Mitchell most frustrated. Another experience that opened Mitchell’s eyes was when he was caught in an air raid noticing “…another series of strong explosions, then the machine gun and anti-aircraft fire. The whole town was, of course, in darkness and everyone had taken to the vaces or vaulted wine cellars inside of houses.” (14) This had a profound effect on Mitchell as he now could see the effect of air power on the morale of the enemy, as well as the reach that such power can have as to make a quick strike from a distance in a short amount of time. An additional event that facilitated Mitchell understanding about the future of air power was a reconnaissance flight that he took with a French pilot over the German lines. Mitchell wrote that he could gain a better picture of the troop formations by air then on the ground. He said, “A very significant thing to me was that we could cross the lines of these contending armies in a few minutes in our airplane, whereas the armies had been locked in the struggle, immovable, powerless to advance for three years…” (15) The combination of these revelations made Mitchell even more fervent in his requests for more support from the United States Army to strengthen and improve their air capabilities. He was looked at by those in Washington as someone of little value when it came to his grasp of aviation, where as he was considered an expert in France. Mitchell would later use his relationship with French premier Alexandre Ribot to coax him to send a message to Washington DC restating Mitchell’s plan, under the guise that it was Ribot’s, requesting twenty thousand planes and forty thousand mechanics. These numbers were much more than the United States could spare, however it awoke the bureaucrats in the American capital and started the process that would eventually lead to a massive aerial force three times the size of the French. (16)

Although this was a victory for Mitchell, his problems with getting the United States aviation capabilities up to date were just starting. The arrival of General John “Black Jack” Pershing added a whole new set of challenges for Mitchell, who felt, “General Pershing himself thought aviation was full of dynamite and pussyfooted just when we needed the most action.” (17) These two strong characters, Mitchell and Pershing, would have many heated discussions on the role of air power and who would command it. Mitchell was tired of having to go through

Billy Mitchell and General Pershing

Washington for all of his requests and wanted one man to be the head of aviation, where Pershing did not see the need for this, feeling that aviation was just a whim. The discussions got so heated between the two that Pershing threatened to send Mitchell back to the states. Mitchell however was not intimidated and became unrelenting in this matter. So as to not have to make due on his threat, Pershing seeing the value of Mitchell, appointed Major General William Kenly as Chief of the Air Service in the fall of 1917 in order to calm Mitchell down and to keep peace. (18)

At this time, Mitchell was known as a bit of a highflier, racing around in his Mercedes and entertaining several up and coming flyers and dignitaries. On one occasion, Mitchell’s Mercedes broke down on a small French road when an Army driver stopped to help him. The driver ended up being able to fix the car due to the fact that he was a racing driver back in America. The driver wanted to be in the Air Service and Mitchell helped make that happen. The driver’s name was Eddie Rickenbacker, America’s first Ace Flyer and one of Mitchell’s greatest contributions to the Air Service. (19)

However, Mitchell’s life was still not all parties and leisure. There was still plenty of work to be done and arguments to be made. A new advisory rose to challenge Mitchell in the form of American Brigadier General Benny Foulois, who was put in command of the United States Air Service. Foulois was an experienced aviator who had no time for Mitchell’s brashness saying Mitchell had an “extremely childish attitude”, and was “mentally unfit for further field service”. (20) This posed yet another issue for Pershing who again saw the value of Mitchell not only as a tactician but also as a liaison to the French. So in order to mediate the situation, Pershing sent Mitchell to the front, and made him commander of all aviation forces there. This was where Mitchell shined the most.

Mitchell about to fly an air mission during the First World War

Mitchell, much like his friend future General George S. Patton Jr., always led from the front and in Mitchell’s case this meant flying missions. One such mission took place when the French and American Armies were being squeezed by the Germans in an attempt to out flank them and head into Paris. A plan was devised to use a combined British and American squadron to patrol the sky. Straightaway, Mitchell saw only disaster for this proposal and made a counter suggestion to fly a reconnaissance mission. This offer was accepted and Mitchell decided to fly the mission himself. He took off after a quick few hours of sleep and headed toward the enemy. Mitchell discovered thousands of Germans marching in columns towards a series of bridges. He quickly turned his aircraft in the direction of the closet allied air field touched down and found the commander spreading the word to start an aerial attack on the bridges. A secondary aerial attack on the German supply base at Fere-en-Tardenois was also suggested by Mitchel and approved by command. Mitchell’s vision saw that this plan, if successful, would turn the German Army around and trap them, thus destroying any chance they had for victory. (21) The action that took place was intense and resulted in the first allied success in the air. Although this success was limited, it started to turn the tide of the war. For his brave reconnaissance flight, Mitchell was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. (22)

Mitchell’s next large scale maneuver was the largest aerial operation of the war consisting of fifteen hundred aircraft, this assault was known as the St. Mihiel offensive. Between September 12th and 16th , the Americans where in total command of the air making thirty three hundred flights into enemy territory racking up four thousand hours of flight time firing thirty thousand rounds of ammunition, making more than one thousand separate bomb attacks using seventy five tons of munitions. This operation resulted in the destruction of sixty enemy planes and twelve enemy balloons, all of this during bad weather. (23)

The First World War established the career of Billy Mitchell; he entered France as a Lieutenant Colonel and was now leaving a Brigadier General with a reputation for having extraordinary leadership and being perhaps the most experienced airmen in the service of the United States Army. On November 11th 1919, the armistice ending the First World War was signed. Before returning to the United States, Mitchell went to London to discuss air strategy with the Chief of the British Air Staff, General Hugh Trenchard. The focus of this discussion was on air independence, concentrating on the theory that the aviation wing of the Army should be a separate service all together. Mitchell was a propionate of this theory and after the talks upon his return to the United States it became one of his major goals. (24)

Left: Sir Huge Trench Right: Major General William Hann

Mitchell’s constant speeches and writings to the Army War Department concerning a separate aviation service and the possibility of air attack from across the globe, made him very unpopular. He was also making enemies amongst members of the Army who were not flyers by questioning their authority on matters of air combat. He had a large quarrel with General William G. Hann, who was a very well established commander at the time. Mitchel insisted that air power alone could win a war and that infantry was a thing of the past. Hann, an infantry commander, took offence and the argument ended in a great deal of destine between both men, Mitchel wrote about the situation saying, “it impressed on me more than ever that, under the control of the army, it will be impossible to develop an air service.” (25) Mitchell’s challengers were not only in the army, he was developing enemies in the navy as well, due to two factors; the aforementioned separate aviation service, as well as a tight military budget. A battle erupted between the Navy and Mitchell over these issues.

The Navy went so far as to send then Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt out on a speaking tour to campaign against the idea of a separate air wing claiming it was ill conceived and would take money away from the navy, making them weaker and a strong navy was essential to keep America safe. (26) Mitchell long felt that the navy was almost obsolete and vulnerable to air attack saying in his book Winged Defense The Development and Possibilities of Modern Air Power –Economic and Military “From a military standpoint, the airmen have to study the effect that air power has on navies and what their future will be. They know that within the radius of air power’s activities, it can completely destroy any surface vessels or war ships. They know that in the last war, surface ships, battleships, cruisers and other sea craft took comparatively little active part.” (27)

Mitchell’s ideas were put to the test in a series of experiments conducted by both the Army and the Navy on the bombing of ships from the air. Multiple vessels were used. One of the vessels used in this series of experiments was the captured German battleship Ostfriesland. The navy had the first chance at destroying the mighty craft, but only succeeded in damaging her. Then Mitchell’s army squadron flew in and obliterated the German warship, sinking her in minutes. Mitchell described the scene this way, “When a death blow has been dealt by a bomb to a vessel, there is no mistaking it. Water can be seen to come up under both sides of the ship and she trembles all over…In a minute the Osterfriesland was on her side in two minutes she was sliding down by the stern; in three minutes she was bottom-side up, looking like a gigantic whale, in a minute or more only her tip showed above water.” (28)

Mitchell’s ideas were put to the test in a series of experiments conducted by both the Army and the Navy on the bombing of ships from the air. Multiple vessels were used. One of the vessels used in this series of experiments was the captured German battleship Ostfriesland. The navy had the first chance at destroying the mighty craft, but only succeeded in damaging her. Then Mitchell’s army squadron flew in and obliterated the German warship, sinking her in minutes. Mitchell described the scene this way, “When a death blow has been dealt by a bomb to a vessel, there is no mistaking it. Water can be seen to come up under both sides of the ship and she trembles all over…In a minute the Osterfriesland was on her side in two minutes she was sliding down by the stern; in three minutes she was bottom-side up, looking like a gigantic whale, in a minute or more only her tip showed above water.” (28)

Although this proved Mitchell’s theory that air power can defeat sea power, his fight to gain funding and a separate aviation service went on to no avail and resulted in his demotion from Assistant Chief of the Air Service. He reverted to his permanent rank of Colonel and was transferred to San Antonio, Texas, as air officer to a ground forces corps. (29) This is where he heard the news about the tragedies of the Shenandoah as well as the ill-fated attempt to fly from San Pablo Bay to Hawaii. Both incidents happened within

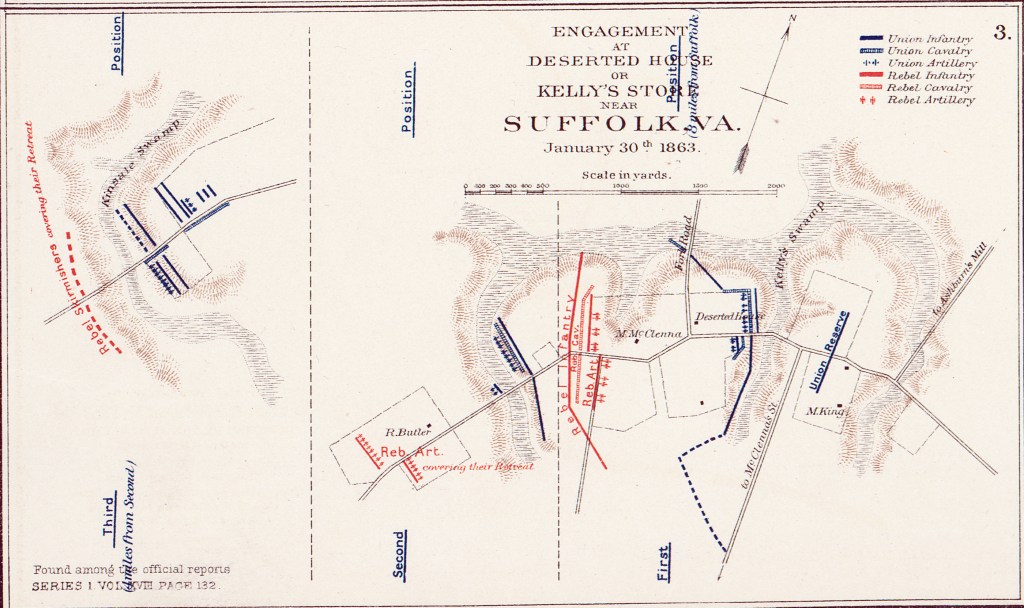

1925: Caught in a squall over southeastern Ohio, the Navy dirigible USS Shenandoah breaks up and crashes into a field, killing 14 of the 43 men aboard.

days of one another and were put on by the navy as well publicized attempts to show naval air superiority they ended in failure and death. The Secretary of the Navy not wanting to admit any wrongdoing issued a statement, “The failure of the Hawaiian flight and the Shenandoah disaster we have come to the conclusion that the Atlantic and the Pacific are still our best defenses. We have nothing to fear from enemy aircraft that is not on this continent.” (30) This enraged Mitchell as it was a slap in the face to everything he stood for and was warning against, therefore he felt compelled to make this statement, about the incidents; to the press, “My opinion is as follows: These accidents are the result of the

incompetency, the criminal negligence, and the almost treasonable administration of our national defense by the Navy and War Departments.” (31) Mitchell was court marshaled and charged with “Conduct to the prejudice of good order and military discipline and in a way to bring discredit upon military service” (32) Mitchell left for Washington DC and was placed under arrest a few days after his arrival. The court-martial record has one million four hundred thousand words and consists of seven large volumes, but in all of those words there was not enough to help Mitchell out of this predicament. (33) By Special order 248 on October 20Th 1925 Mitchell was found guilty and received what was considered a light sentence due to his heroic service in the First World War. The sentence consisted of a suspension of rank and command, plus forfeiture of pay for five years. Mitchell retired from the service one year later in disgrace. (34) The next ten years Mitchell spent time with his family and traveled around the country discussing air power still as feisty as he was during his many campaigns before Congress. He died of heart failure in 1936 a man ahead of his time but looked

The Court Martial of Billy Mitchell

upon then as an agitator and a crackpot.

Billy Mitchell is now revered by many and his doctrine has become the bases for the American Air Force which is now a separate branch of service something Mitchell fought so hard for but would never see in his life. He is a true war hero and a visionary whose grandiose ideas were way ahead of his time ending his career in disgrace. He was a man who never faltered from his beliefs, making him one of the greatest military leaders in the history of the United States of America.

1) Jones, Johnny R. William “Billy” Mitchell’s Air Power. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2004 Pg. 3

2) Davis, Burke. The Billy Mitchell Affair. New York: Random House, 1967. Pg. 15

3) Davis, Pg. 17

4) Ibid

5) Mitchell, Ruth. My Brother Bill. New York: Harcourt, Brace And Company, 1953. Pg. 49

6) Davis, Pg.’s 18-19

7) Hurley, Alfred F. Billy Mitchell, Crusader for Air Power. New ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975. Pg. 10

8) Ibid, Pg. 11

9) Ibid,

10) Ibid,

11) Ibid,

12) Ibid, Pg. 21

13) Davis, Pg. 29

14) Schwarzer, William. The Lion Killers Billy Mitchell and the Birth of Strategic Bombing. Mt. Holly: Aerial Perspective, 2003. Pg. 20

15) Davis, Pg. 30

16) Ibid, Pg. 32

17) Ibid, Pg. 35

18) Ibid, Pg. 35

19) Ibid, Pg. 36

20) Ibid

21) Levine, Isaac Don. Mitchell Pioneer of Air Power. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1943. Pg.’s 120-121

22) Ibid, Pg. 127

23) Ibid, Pg.’s 132-135

24) Cook, James. Billy Mitchell. Boulder: Lynne Reinner Publishing, 2002. Pg. 107

25) Cooke, Pg. 114

26) Ibid, Pg. 115

27) Mitchell, William. Winged Defense The Development and Possibilities of Modern Air Power, Economic and Military. New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons, 1925. Pg. 99

28) Ibid, Pg. 72

29) Burlingame, Roger. General Billy Mitchell Champion of Air Defense. New York: McGraw-Hill , 1952.Pg. 141

30) Ibid, Pg. 148

31) Mitchell, Pg. 301

32) Cooke, Pg. 180

33) Gaureau, Emile, and Cohen, Lester. Billly Mitchell Founder of Our Air Force and Prophet Without Honor. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co , 1942.Pg. 135

34) Cooke, Pg. 217